Introduction: The Tunisian Revolution

The Jasmine Revolution began in late 2010, and resulted in the ouster of the dictator Zine el Abidine Ben Ali on 14 January 2011. Ben Ali ruled Tunisia with an iron fist from November 1987, following his removal of the founder of the Tunisian Republic, Habib Bourguiba, through what was dubbed a ‘medical coup’.

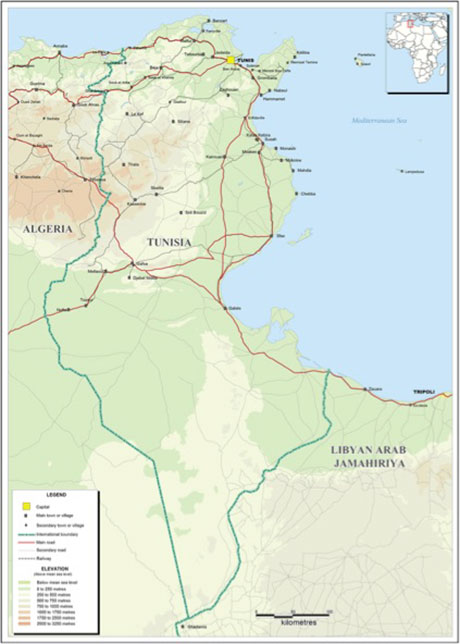

Four years after the Jasmine Revolution, Tunisia has made some great strides in its transition towards a democratic political order. The peaceful revolution by civil society and the powerful trade union, the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), had sent shockwaves, causing other uprisings throughout the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Tunisia is the smallest country in the Maghreb, with a population of 11 million people. Unlike what took place in other parts of the world, the revolution did not revert to authoritarianism – like Egypt – or experience chaos – as in Libya, Syria and Yemen. The relatively successful transition is becoming not only a model, but it has debunked the myth of the impossibility of the Arab world building democratic orders.1 What makes Tunisia’s revolution rather unique in the MENA region is that, in spite of the riots that took place in the mining region of Gafsa in 2008, barely any observers thought that three years later, Tunisians would be able to force out the dictator and his administration, or to defeat the powerful, brutal security apparatus that numbered more than 130 000 members. The refusal of the military – which had remained a republican institution as intended by Bourguiba, and which was marginalised by the Ben Ali regime2 – to shoot at people partly accounts for the success of the uprising. The will of Tunisians, who no longer feared the tyrannical regime and risked their lives to gain their freedom, was the major factor in bringing down the regime. The determination of Tunisians to achieve their transition without outside interference adds to their credit.

Tunisia Under the Ben Ali Regime

The Ben Ali regime had maintained itself through sheer repression; an impressive security apparatus controlled the population and suppressed any kind of political protest, no matter how benign it was. The regime, however, sought legitimacy through the holding of regular elections – which, of course, the president won overwhelmingly, usually with over 90% of the votes, while his party, the Republican Democratic Party (RCD), won all the seats in the legislature. When Ben Ali came to power, he changed the constitution to impose limits on presidential mandates, but then removed those limits so he could stay in office for life. He ran for re-election periodically, basically unopposed, since the other presidential hopefuls were disqualified or harassed. Scholars refer to such elections as ‘electoral authoritarianism’,3 or ‘new authoritarianism’,4 which MENA regimes resorted to in order to survive the Third Wave of democratisation or to please their benefactors in the United States (US) and Europe. With regard to the economy, the regime was favourably received by international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and by Western powers, which saw Tunisia as a model.5 The Tunisian government followed the recommendations of the IMF to the letter. However, the economy was not so efficient and corruption perverted its functioning; it could no longer create jobs for graduates in a country where the youth are dominant. Privatisation of the economy mostly benefited the Ben Ali families and their patrons, who controlled most sectors of the economy. Furthermore, the regime opposed genuine democratic reforms under the pretext that there could be no prosperity and economic growth (under a liberal system) without the required political stability. Yet, unemployment increased constantly. There were huge disparities between the northern urban and littoral zones – which were dominated by the industrial, tourism and agriculture sectors, and received investments, and benefited to a certain degree from international trade and commerce – on the one hand, and the southern and western centres – which witnessed far higher unemployment and poverty levels – on the other hand. This explains why the riots that followed the immolation of a young graduate on 17 December 2011 took place in the western city of Sidi Bouzid – a region that, like many others, was neglected by the government. Thus, the conditions of high unemployment, especially among the youth (estimated at 40%), nepotism, bad governance, corruption, repression, lack of freedom and ageing leaders, which prevailed in other MENA countries too, were among the major factors that led to the uprisings.6

The Revolution: The End of the Dictatorship

The spontaneous riots, which were directed by no political party or any ideological movement – similar to what occurred in Egypt – mobilised large segments of the population. The regime was incapable of reacting to such a wave of protesters, who demanded no less than the end of the regime, thus forcing Ben Ali to escape into exile in Saudi Arabia on 14 January 2011. The military took charge of securing the country, while pledging not to interfere in the political process. Under pressure from a highly mobilised civil society, which rejected the political procrastinations of the interim authorities through incessant protests, the latter succumbed to society’s increased pressure to allow for a fully-fledged democratic transition. Ben Ali’s party, the RCD, was dissolved and the Political Reform Committee, set up after his departure, was fused into the 155-member Committee to Defend the Revolution, eventually renamed the Higher Commission for the Achievement of the Objective of the Revolution, of Political Reform and the Transition to Democracy.7 The State Security Division and other offices of the political police were disbanded, jettisoning the last institutional strongholds of the old regime. This process was ensured by the armed forces, who maintained their pledge to not interfere in politics other than protect it from reversal by forces of the old regime.

The members of the Higher Commission decided that the crucial first stage of the transition would be the full revision of the constitution and tackling the inequalities of power, which had so greatly benefited the president over the legislative branch of government, eventually leading to a dictatorship. They also decided on the election of a Constituent Assembly, which came to life in October 2011. A genuine democratic process was thus underway and saw the creation of an independent electoral commission – the instance supérieure independante pour les élections (ISIE) – and a number of laws standardising the funding and electioneering of political parties.

The democratic process also consisted of not only authorising the many newly created political parties, but also legalising the Islamist Ennahda party, which had been banned under the Ben Ali regime and whose leaders had been imprisoned or forced into exile, including its charismatic chief, Rachid Ghannouchi. Ghannouchi, considered a moderate Islamist committed to democratic practices and institutions of government, declared that his party would not seek to amend the progressive Personal Status Code of 1957, which had guaranteed Tunisian women an exceptional (for the Arab region) package of rights, including full equality as citizens and the right to education. He also declared not to impose shari’a law as the foundation of the Constitution.8 He thus rescinded his initial claim of making Tunisia an Islamic state.

Surprisingly, and to the dismay of secularist forces, Ennahda won the first democratic election of the Constituent Assembly, with over 41% of the popular vote (89 out of 217 seats),9 although failing to secure an absolute majority. This shortcoming compelled the party to join a coalition with two smaller, more secularist, social democratic parties – the Congrès pour la République (CPR), headed by long-time regime opponent, Moncef Marzouki, with 29 seats; and the Forum démocratique pour le travail et les libertés (FDTL, also known as Ettakatol), with 20 seats – to form an interim ‘troika’ government. The Ennahda’s efficient campaigning had paid off. The secularists failed to mobilise voters who still saw Ennahda as the most ardent opponent of the Ben Ali regime, of which it was the biggest victim. Ghannouchi had convinced large segments of society that Islam and democracy were compatible and that pluralism was not antithetical to Islam – views that he had expounded well before the revolution.10

The 2011 election was generally free, transparent and fair, and stood in contrast to most elections held in the Arab world and Africa. Many factors explain this outcome during the Tunisian transition: a well-educated population, the existence of institutional structures (contrary to Libya, for instance, which practically had none), strong trade unions (mainly the UGTT), professional associations (such as lawyers’ associations), and respect for the rule of law.

Another factor is the homogeneity of Tunisian society – which, although it has some divisions, does not suffer from fragmentation along religious, political, cultural or ethnic lines, as is the case of Syria or Iraq, for instance. This factor accounts for the promulgation of a national Constitution on 27 January 2014,11 resulting from a protracted process that met the approval of all political and societal actors. Tunisia’s new constitution is the most democratic and liberal in the Muslim world – it protects civil liberties; separates legislative, executive and judicial powers; guarantees women parity in political bodies; and declares that Islam is the country’s official religion, while protecting religious freedom for all.

The troika government faced many challenges, including a sense of betrayal felt by members of the two smaller parties in the National Constituent Assembly (ANC). They believed that their respective parties made too many concessions to Ennahda, and thus withdrew from the ANC.12

During the rule of the troika, a new party made its appearance in July 2012. Led by Béji Caïd Essebsi, minister of the interior under Bourguiba and prime minister in the first provisional government of 2011, Nidaa Tounès proved to be a potent challenger to the troika. The new party, which attracted young people, trade-union activists, anti-Islamists, secularists, former members of the RCD and defectors from the two parties in the coalition with Ennahda, presented itself as a secular, modernist alternative to Ennahda and to those who wished to undo the gains of ‘modern Tunisia’.

The Legislative and Presidential Elections of 2014: The Consolidation of the Democratic Transition?

Regardless of the many changes of government and the tensions that prevailed in state and society, Tunisians succeeded in resolving those problems through peaceful means. The assassination of two popular leftist activists, Chokri Belaïd in February 2013 and Mohamed Brahmi in July 2013, almost derailed the transition in Tunisia. But, pressure from civil society, trade unions and new alliances among political parties forced the government to act more decisively to bring about stability and crack down on Islamist extremists. The emergence of Salafist extremists, whom Ennahda failed to confront compellingly – although concerned by their rise – resulted in accusations that Ennahda was complicit in those assassinations. The assassinations and the catastrophic economic situation, coupled with insecurity at the borders with Libya, tarnished the image of Ennahda and resulted in a sharp drop in its popularity. On 28 September 2013, Ennahda capitulated under heavy protests and demonstrations, and the government agreed to resign in favour of a negotiated technocratic caretaker government that would carry the country through to new elections. Ennahda’s decision proved that the party lived up to its promise that it would only come to power via the ballot box, and would leave office through the same process. Whatever suspicions existed about the party since 2011, Ennahda showed respect for the political process in times of triumph and defeat. This also shows that Islamism can operate within a democratic system without necessarily undermining the foundations of democracy.13

The legislative election held on 26 October 2014 confirmed that Tunisia’s democratic process remained on track. The election took place with no major incidents and saw the surprising defeat of Ennahda and the victory of Nidaa Tounès. Undoubtedly, Ennahda’s failure to tackle Tunisia’s socio-economic challenges, its neglect of the hinterlands, and the widespread political corruption caused its electoral defeat. On 23 November 2014, Tunisians went to the polls again to elect their new president – the first completely democratically elected president since the country’s independence in March 1956. The election also ended the presidential system and one-party rule in the country – most of the executive power will henceforth be in the hands of the prime minister, who will be responsible before parliament. Out of 22 candidates with different profiles, two candidates made it to the run-off: Marzouki and Essebsi, who garnered 33.43% of the votes and 39.46% of the votes respectively.14 In the second round, Essebsi defeated Marzouki, who was favoured by the Islamists with whom he had worked in the troika, with a comfortable 56.68% of the votes, Marzouki receiving 44.32%.15 Given that Nidaa Tounès gained 86 seats in parliament – a figure below the 109 required to form a government – it was necessary to enter coalitions. Therefore, negotiations for a coalition government were ongoing for 100 days after the legislative election before the head of the executive, Habib Essid, was able to present his government to parliament on 4 February 2015. Ennahda accepted being under-represented in government, with only one ministerial portfolio and three secretaries of state.16 Undoubtedly, the party accepted this under-representation to avoid the Egyptian scenario whereby the military intervened to suppress the Muslim Brotherhood. Regardless, the coalition that has been entered is composed of technocrats, whose main objectives consist of addressing as a priority Tunisia’s dire socio-economic conditions and the insecurity prevailing at its western border with Algeria and eastern border with Libya. While the political transition has been successful overall, the difficult economic situation may pose a threat to its consolidation.

The Economy: The Achilles Heel of Tunisia’s Democratic Transition

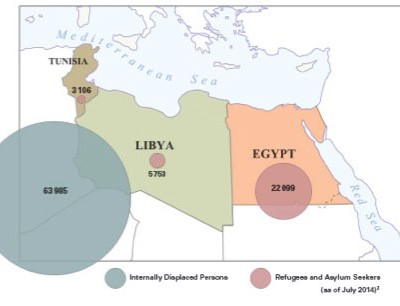

While Tunisia’s economic challenges were apparent prior to the revolution, conditions since then have worsened. Socio-economic conditions, especially in the interior regions, were quite difficult. But the situation deteriorated further with the fallout of the Libyan armed uprising that began in February 2011.17 Gaddafi’s fall has had particularly disastrous repercussions on post-revolutionary Tunisia. Before the war in Libya, Tunisia and Libya had the highest volume of trade between any two North African countries – and this grew at an average of 9% every year between 2000 and 2009. For its part, Libya absorbed 6.9% of Tunisia’s exports, making it Tunisia’s second-largest export market after the European Union. With the uprising in Libya, all this came to an end. In the first quarter of 2011, Tunisia’s exports to Libyadropped by 34% and imports fell by an astounding 95%.18 According to the African Development Bank, these changes were direct consequences of the civil war in Libya.19 In addition, more than half of the 100 000 Tunisians who had been working in Libya flooded back home. The remittances they sent home – an estimated 125 million Tunisian dinars before the war – virtually disappeared.20 Meanwhile, Tunisia’s unemployment skyrocketed from 14.2% in 2010 to 18.9% by the end of 2011, undoubtedly due in part to the returning expatriates.21 Libyans, who had previously visited Tunisia in droves, stayed at home. From 1.5 million tourists each year, the year ending in May 2012 saw only 815 000 Libyan guests – all bad news for an economy that depends on visitors – tourism makes up 11% of Tunisia’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 14% of employment.22 The drop in tourism caused the economy to backslide. In summer 2014, the situation was somewhat alleviated because of the many Algerian tourists who visited the country and saved the tourist season.23 But the security situation discouraged Western tourists and investors to come to Tunisia.

Tunisia’s GDP growth has averaged 2.3% annually since the fall of Ben Ali’s regime. This can be blamed on the political-economic expediency of the troika, which increased wages overall by 40%, while productivity grew by a mere 0.2%.24 “The cost of state subsidies to oil-and-gas products and foodstuffs has rocketed by 270% over three years. The budget deficit was 7% in 2013 and is expectedto rise to 9% in 2014. Foreign debt has risen by 38% over three years to over 50% of GDP. Such figures are unsustainable… The explosion of the informal sector, caused by the failure of the formal economy to provide jobs, is now fuelling inflation.”25

The socio-economic situation has also had some direct repercussions on the security situation prevailing in the country.

Security: The Threat of Salafist Jihadists

Once in power, Ennahda freed thousands of Islamist militants, some of whom were Salafist jihadists, imprisoned by the Ben Ali regime. Ennahda permitted Salafist preachers to exploit mosques across the country as platforms. “By early 2014, 90% of Tunisia’s mosques were under the control of Salafists, which facilitated the propagation of jihadist messages. Those messages resonated with some youth, who had been marginalised under Ben Ali and continued to live on the margin following the 2011 revolution as Tunisia’s economy struggled to recover.”26 As happened in Algeria in the 1990s, self-proclaimed imams manipulated the marginalised youth who were unable even to read the Quran, and provided them with an extremist interpretation that enticed them to join the jihad against the regimes in various Muslim countries, notably in Iraq and Syria (3 000 Tunisian jihadists are said to have joined the fight there).27 The desperate socio-economic conditions have favoured the recruitment and co-option of young people by jihadist networks. The youth, who lost confidence in state authorities, have engaged in the informal sector – organised crime and (arms) smuggling have thrived as a way of surviving in the destitute areas and/or to pursue jihad. Faced with this dangerous security situation, the authorities have restored the intelligence services, which had been dismantled in the post-revolutionary period, and reformed the police force. The country has also relied on Algeria to assist it in the fight against terrorism. Tunisia’s armed forces, however, lack the means to fight the jihadists, who are better armed and are able to escape into safe havens in Libya.

Conclusion

In spite of many remaining challenges and hurdles, Tunisia’s transition to democracy is already a success story in the Arab, African and Muslim world. Overall, the transition has been peaceful and the various political parties, civil society, media, trade unions and associations have demonstrated a level of political consciousness and tolerance unrivalled in the MENA region. The main tasks of the new government are now to bring about greater stability, revamp the economy and restore Tunisians’ confidence in the state and in the democratisation process.28 Tunisia today holds the Arab world’s expectations and hopes for authentic democratisation. The country has shown the necessary maturity to bring the democratic process and consolidation to completion.

Endnotes

- The main exponents of such theses are Bernard Lewis, Daniel Pipes and Samuel Huntington, among others. For an excellent critique, see, Sadowski, Y. (1993) ‘The New Orientalism and the Democracy Debate’, Middle East Report, 183, Available at: <http://chenry.webhost.utexas.edu/civil/2007/Sadowsky/0.pdf>.

- Brooks, Risa (2013) Abandoned at the Palace: Why the Tunisian Military Defected from the Ben Ali Regime in January 2011. Journal of Strategic Studies, 36 (2), pp. 205–220.

- Cavatorta, F. and HaugbÇ¿lle, Rikke Hostrup (2012) The End of Authoritarian Rule and the Mythology of Tunisia Under Ben Ali. Mediterranean Politics, 17 (2), pp. 179–195; Snyder, Richard (2006) Beyond Electoral Authoritarianism: The Spectrum of Nondemocratic Regimes. In Schedler, Andreas (ed.) Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner.

- King, S.J. (2009) The New Authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- The US, for instance, repeatedly praised Tunisia as an example of successful socio-economic progress. See Zoubir, Yahia (2009) The United States and Tunisia: Model of Stable Relations. In Looney, Robert (ed.) Handbook on US Middle East Relations. London and New York: Routledge.

- Zoubir, Y. (2012) The Arab Turmoil: An Exploratory Interpretation. The Maghreb Review, 37 (3–4), pp. 323–333.

- Murphy, E.C. (2013) The Tunisian Elections of October 2011: A Democratic Consensus. The Journal of North African Studies, 18 (2), pp. 231–247.

- Author’s interview with Rachid Ghannouchi, Tunis, April 2011.

- The Carter Center (2011) ‘National Constituent Assembly Elections in Tunisia, October 23, 2011 – Final Report’, p. 54, Available at: <http://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/election_reports/tunisia-final-Oct2011.pdf> [Accessed 10 November 2011].

- Ghannouchi’s political thoughts are developed in Tamimi, Azzam (2001) Rachid Ghannouchi: A Democrat within Islamism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The constitution is available at: <http://www.businessnews.com.tn/bnpdf/Constitutionfrancais.pdf>. The members of the National Constituent Assembly overwhelmingly cast their votes in favour of the adoption of the new constitution, with 200 in favour, 12 against and four abstaining.

- Antonakis-Nashif, A. (2013) ‘Tunisia’s Legitimacy and Constitutional Crisis: The Troika Has Failed’, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), Available at: <http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2013C26_atk.pdf> [Accessed 5 September 2013].

- Muasher, M. and Bentivoglio, K. (2014) ‘Tunisian Parliamentary Elections: Lessons for the Arab World’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Available at: <http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=57049> [Accessed 5 November 2014].

- Wolf, Anne (2014) ‘Power Shift in Tunisia Electoral Success of Secular Parties Might Deepen Polarization’, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP Comments 54), Available at: <http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2014C54_wolf.pdf> [Accessed 3 January 2015].

- ElShayyal, Jamal (2014) ‘Essebsi Declared Tunisia Presidential Winner’, Al Jazeera, 22 December, Available at: <http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/12/essebsi-declared-tunisia-presidential-winner-2014122212464610622.html> [Accessed 26 December 2014].

- Ben Tarjem, Khansa (2015) ‘Un nouveau gouvernement tunisien, sans enthousiasme’, (‘A New Tunisian Government, Without Enthusiasm), Le Monde, 6 February, Available at: <http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2015/02/06/un-nouveau-gouvernement-tunisien-sans-enthousiasme_4571136_3212.html> [Accessed 10 February 2015].

- Zoubir, Y. (2012) ‘The Libya Spawn, What the Dictator’s Demise Unleashed in the Middle East’, Foreign Affairs, July, Available at: <http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/137796/yahia-h-zoubir/qaddafis-spawn>.

- Santi, E., Ben Romdhane, S. and Ben Aïssa, Mohamed Safouane (2011) ‘Impact of Libya’s Conflict on the Tunisian Economy: A Preliminary Assessment’, p. 7, Available at: <http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/The%20Impact%20of%20Libyan%20Conflict%20on%20Tunisia%20ENG.pdf> [Accessed 10 April 2012].

- Kaouther, A. and Castel, V. (2012) ‘Inflation in Tunisia: Perception and Reality in a Context of Transition’, Available at: <http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/ECON%20Vincent%20notes%20avril%202012%20anglais_ECON%20Vincent%20notes%20avril%202012%20anglais.pdf> [Accessed 5 May 2012].

- Santi, E., Ben Romdhane, S. and Ben Aïssa, Mohamed Safouane (2011) op. cit., p. 8.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Author’s interview with Tunisian official, Addis Ababa, 30 January 2015.

- Ghilès, Francis (2014) ‘Tunisia Turns a Political Corner but IMF Inspired Measures May Not Offer the Right Economic Prescription’, CIDOB Note, 86, Available at: <http://www.cidob.org/en/publications/notes_internacionals/n1_86/tunisia_from_hope_to_delivery> [Accessed 2 February 2015].

- Ghilès, F. (2014) ‘Tunisia has Made Strides in Democratic Transition: Can It Get the Economy Right?’, Available at: <http://www.juancole.com/2014/04/tunisia-democratic-transition.html>; see also Ghilès, F. (2013) ‘Still a Long Way to Go for Tunisian Democracy’, The Maghreb Center Blog – Informed Analyses and Commentaries on North African Affairs, Available at: <http://themaghrebcenterblog.org/still-a-long-way-to-go-for-tunisian-democracy-francis-ghiles-financial-times-north-africa-correspondent-from-1981-to-1995-senior-researcher-at-cidob-and-maghreb-center-associate/> [Accessed 5 February 2015].

- Khatib, Lina (2014) ‘Tunisia’s Security Challenge’, Carnegie, Available at: <http://carnegie-mec.org/2014/11/26/tunisia-s-upcoming-challenges/hvfs> [Accessed 27 November 2014]. For a thorough economic analysis, see United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2014) ‘Tunisia: Economic Situation and Outlook in the Current Transition Phase’, Available at: <http://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/publications/note_tunisie_eng.pdf> [Accessed 5 February 2015].

- Mölling, Christian and Werenfels, Isabelle (2014) ‘Post-election Tunisia: Security Issues as a Threat to Democratisation Germany Should Help Reform and Strengthen the Security Sector’, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SPW Comments 53), Available at: <http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2014C53_mlg_wrf.pdf> [Accessed 10 January 2015].

- A 2014 Pew Research Center poll found that 30% of Tunisian youth believe that the system of government “doesn’t matter”; only 13% were “satisfied with the country’s direction”. Overall, censuses steadily recount a feeling that life was better under Ben Ali’s regime, especially for the 2 million government workers, because there was stability and institutional coherence. Therefore, Tunisians wish to have a stable government that meets their security and economic needs. Pew Research Center (2014) ‘Tunisian Confidence in Democracy Wanes: Ratings for Islamist Ennahda Party have Declined Since Revolution’, Available at: <http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/10/15/tunisian-confidence-in-democracy-wanes/> [Accessed 20 October 2014].