From independence to civil war

The independence of South Sudan was the culmination of a 6-year process which began with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of 2005. The UN oversaw the implementation of the CPA and organised a referendum in January 2011 to determine the status of South Sudan.

The UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) took over from the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) on 8 July 2011, the day before South Sudan’s independence. On 15 December 2013, violence broke out between two factions of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), which quickly spread across most of the rest of the country. A peace agreement, the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS), was signed in August 2015 and lasted for almost a year before it violently broke down in July 2016. The war raged on for a further 3 years before a new peace agreement was reached in September 2019, the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS).

The peace process in #SouthSudan is still highly vulnerable to relapse. The peace agreement has brought large-scale fighting to an end, but communal conflict has flared up and will most likely be a major cause of instability and displacement in the year ahead @CedricdeConing

Tweet

When the civil war started in December 2013, the Government of South Sudan accused UNMISS of supporting the opposition forces and although the relationship has improved since then, it remains challenging. A study into the effectiveness of UNMISS undertaken by the Effectiveness of Peace Operations Network (EPON) in 2019 found that obstructions to the freedom of movement of the mission by the Government and other actors was a major factor impeding the performance of the mission. An independent review commissioned by the Security Council late in 2020 similarly found that such obstructions were “the single most important factor limiting the Mission’s ability to carry out its mandated activities.”

The outbreak of the civil war in 2013 triggered one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world. Thousands of people died in the conflict and hundreds of thousands more fled the violence. As of March 2021, more than 1.6 million South Sudanese remain internally displaced and approximately 2.2 million South Sudanese have sought refuge in neighbouring countries and beyond.

When the civil war started thousands of civilians sought safety in UN compounds in Juba, Bor, Akobo, Bentiu, Malakal and Melut. UNMISS had to adapt rapidly from a mission geared to build new state institutions to a mission providing protection to thousands of Internally Displaced People (IDPs). Almost overnight, UNMISS also became responsible for facilitating the feeding, health and safety of the people under its care. At its height UNMISS was responsible for more than 200,000 people in newly formed Protection of Civilians (POC) sites adjacent to the UN bases. The EPON report found that without the direct protection and broader actions undertaken by UNMISS, tens of thousands more people would have died during the civil war in South Sudan.

These developments radically changed the mission’s role. In addition to protecting and caring for civilians, the UN also became responsible for monitoring and promoting human rights, for providing protection to and assisting humanitarian action, and for contributing to support the efforts to end the war. Once the peace agreements were signed in 2015 , UNMISS had an important additional role to support the Cease-fire Transitional Supporting Arrangement Mechanism (CTSAM) and the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC). Following the signing of the 2018 peace agreement, UNMISS has continued to support the Revitalized-JMEC and the CTSAM.

In 2020, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated many of these vulnerabilities and contributed to delays in the implementation of the peace process. The capital Juba has been especially affected and several politicians, government officials, and international staff, including UN peacekeepers, have tested positive.

New priorities for UNMISS in the year ahead

The independent review commissioned by the UN Security Council released its report in January 2021. It found that the R-ARCSS contained a clear vision for securing peace in South Sudan, but that its implementation has been slow and uneven. The review found that instead of prioritizing those elements of the agreement that would strengthen governance and accountability, the parties to the agreement focused on elite power-sharing arrangements. What is important is that the review concluded that although the R-ARCSS has been successful in reducing large-scale fighting and bringing most parties of the conflict into dialogue, it has not yet addressed the underlying drivers that triggered and fuelled civil war in South Sudan. The current peace process is thus still very fragile and the review recommended that the mission prioritizes actions to support the implementation of the peace agreement.

This year will be critical for #SouthSudan. @UNMISSmedia has an important role to play in supporting the Govt @IGADPeace & @AU_PSD to implement the peace agreement, to prevent and manage communal conflict and to prevent and manage the spread of #COVID19 @CedricdeConing

Tweet

The UN Security Council considered the report of the independent review and the UN Secretary-General’s recommendations and renewed the mandate of UNMISS for a year on 12 March 2021. Although the four core elements of the mandate remain unchanged, a number of specific tasks was added. For example, regarding the support to the peace process, the mission was tasked to provide by 15 July 2021, a needs assessment for creating an enabling environment for elections. New tasks also include strengthening the coordination with relevant regional actors like the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the African Union (AU). The new mandate has also re-designated the POC sites as IDPs camps, signalling a change in posture for UNMISS and greater responsibility for the UN and other humanitarian actors in managing these camps. Three of the five POC sites have already been re-designated. The new mandate also tasks UNMISS to support the Government, through technical assistance and capacity building, to help build and reform the rule of law and justice institutions. This represent the start of the return of the peacebuilding elements of the original UNMISS mandate, that was interrupted by the civil war. The new resolution also no longer makes any reference to the Regional Protection Force (RPF) which was mandated after the July 2016 violence to help stabilize the capital Juba, but which was never fully deployed due to objections and obstruction by the Government.

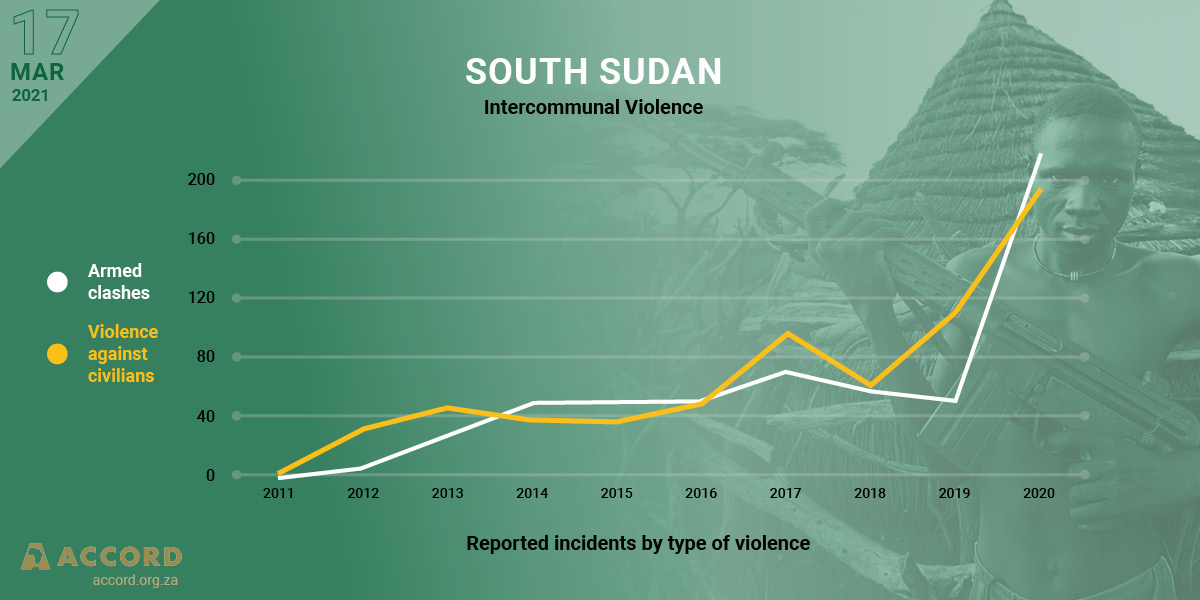

The new resolution also strengthens the language on the adverse effects of climate change on the humanitarian situation and stability in South Sudan, and it tasks UNMISS (and urges the Government) to include climate-related security risks into its comprehensive risk assessments and risk management strategies. This is important because although the R-ARCSS has more-or-less brought large-scale fighting to an end, inter-communal conflict – which was a major cause of fatalities and displacement before the civil war – has significantly increased since 2019. These conflicts will be a major source of instability and displacement in the years ahead if the national, state and local governments and communities, with support from UNMISS and other international partners, are not able to prevent and manage these disputes before they turn violent.

The next year will thus be critical for South Sudan and UNMISS. UNMISS has an important role to play in supporting the Government, IGAD, the AU and other international partners with the implementation of the peace agreement, prevention and management of inter-communal conflict, as well as with the prevention and management of the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cedric de Coning is a senior advisor for ACCORD. He is a research professor with the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) where he co-directs the NUPI Centre on UN and Global Governance.