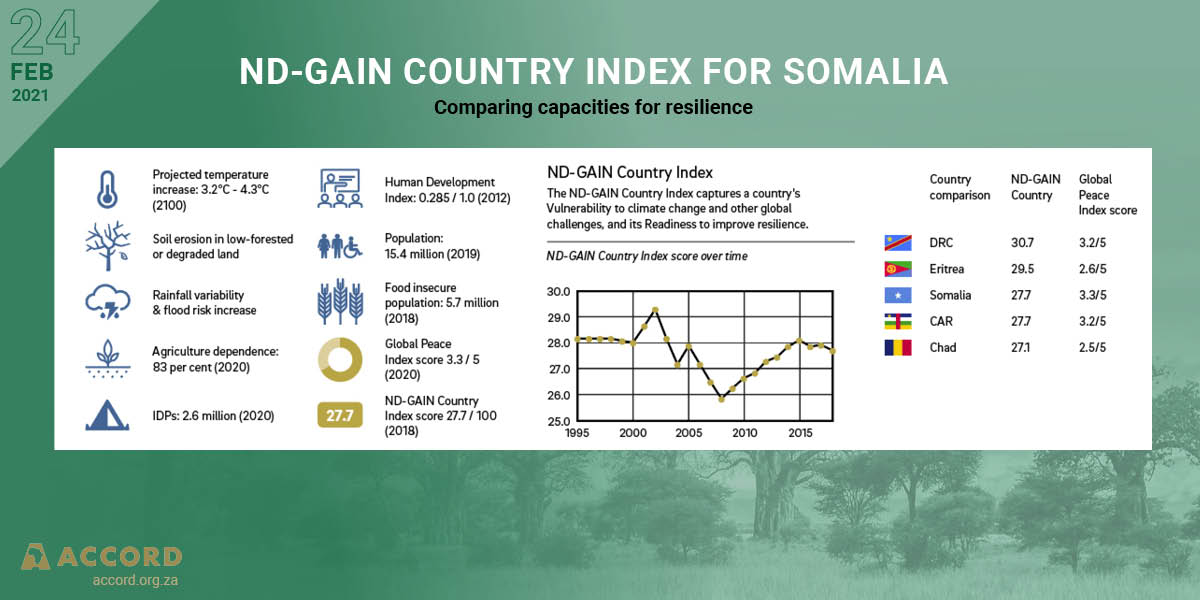

Somalia is very susceptible to the effects of climate change and extreme weather. There has been a gradual, continuous temperature increase of 1 to 1.5°C since 1991, and projected increases of 3.2 to 4.3°C by 2100. Disasters like extended droughts, flash floods and cyclones, have become more frequent in the past 25 years, and the effects of longer-term climatic change – erratic rainfall, disrupted monsoon seasons, strong winds, storms and soil erosion – make fewer headlines but pose a serious threat to 83 per cent of the population reliant on agriculture, pastoralism, hunting, forestry and fishing. The impact of COVID-19 in Somalia is an additional stressor, given the pandemic’s effects on vulnerable groups, services and institutions.

The February 2021 mandate renewal for @amisomsomalia is an opportunity to review what we know about #climatechange and security in #Somalia, and to consider what governments and multilateral organisations can do to improve the way they manage climate related security risks. @AnabGrand & @tarif_kh

Tweet

High dependence on renewable natural resources makes the Somali population very vulnerable to climatic change. As seasonal patterns become harder to predict and adverse weather events occur more frequently, herders and farmers face new challenges because their livelihoods are tied to specific seasons. Dust storms and droughts, stronger winds and notably hotter temperatures adversely affect communities dependent on agriculture and livestock, increasing the risk of resource competition. Somali community leaders told the authors of the 2013 National Adaptation Programme of Action on Climate Change that droughts have fuelled herder-farmer conflicts over diminished pastures and access to water. The COVID-19 pandemic has also had indirect socio-economic effects in Somalia. The International Organization for Migration estimates that 40 per cent of Somali households depend on remittances, which dropped precipitously as a result of worldwide travel restrictions, leaving families less resilient to future shocks.

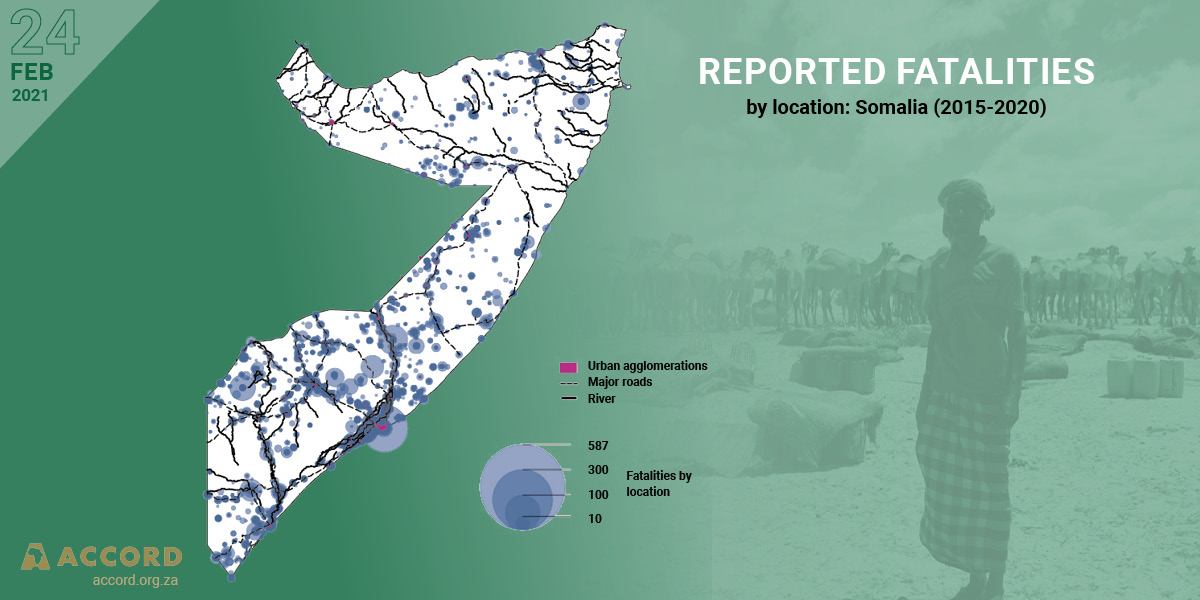

In 2019, over 2.6 million Somalis were displaced by factors including war and climate disasters. Some 53 000 of the displaced came from communities where crops had failed, in turn reducing livestock profitability. Large-scale migration and changing mobility patterns resulting from climate impacts can place additional burdens on the economic resource base in receiving areas, increasing the risk of conflict between hosts and new arrivals. In Somalia, some internally displaced persons (IDPs) sites have been hotspots for clan conflict, as sudden influxes of different communities upend local clan compositions and threaten the control of dominant groups. Climate change, migration and conflict have also intersected when IDPs are targeted for recruitment to armed groups. COVID-19 has placed strain on essential humanitarian services for IDPs, including health services, education, food aid and psychosocial support, leaving vulnerable constituencies even more exposed. In order to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) has imposed measures to limit movement and social interaction; and whilst these actions are necessary to limit the spread of the virus, they place an additional burden on communities that rely on trade and other livelihoods which require social interaction.

The impact of #COVID-19 in #Somalia is an additional stressor, given the pandemic’s effects on vulnerable groups, services and institutions. @AnabGrand & @tarif_kh

Tweet

Armed groups like Al Shabaab have benefitted from climate impacts to boost recruitment and advance control. In the aftermath of droughts and floods, the group has sometimes positioned itself as an alternative service and relief provider in areas the FGS and the Federal Member States (FMS) do not control. Al Shabaab has also used COVID-19 as an opportunity to engage local communities and boost support; for example, the group opened a coronavirus treatment centre in June 2020. Data shows that Al Shabaab increased the number of attacks in 2020, as if to take advantage of an already challenging period.

Local conflict, rather than civil wars, is a more likely outcome of environmental degradation due to climate change. However, small-scale tensions can increase the risk of broader conflict when exploited by elites. Our research on Somalia identified cases where powerful clan militia targeted minority communities with looting and violence, specifically with attacks on livestock and food stores. Climate-related clan and other local disputes need to be resolved before they turn violent. As a result of the political tensions between President Farmaajo, the FMS and opposition politicians over the electoral process, the risk of further political violence is high, and the political uncertainty further undermines the ability of the government at federal and member state levels to adequately respond to the challenges posed by the pandemic, the impacts of climate change, and Al Shabaab.

AMISOM can boost its responses to climate peace and security risks in Somalia by:

- Enhancing its climate-related security risks analysis and reporting on how climate security issues affect its mandate;

- Integrating climate-related security risks in its protection of civilians planning with African Union (AU) support, including use of the AU’s Continental Early Warning System (CEWS); and

- Increasing its preparedness to provide support, on request, to the FGS, FMS and humanitarian actors for responding to slow- and rapid-onset climate impacts.

COVID-19 has already compounded existing vulnerabilities, including those contributed by climate change impacts, and these combined pressures have placed additional stress on vulnerable groups, services and institutions. Anticipatory preventive responses to climate-related security risks, including environmental peacebuilding, can strengthen the resilience of IDPs and local communities – especially women and youth – and contribute to climate-proofing governance, basic service provision and peace and security efforts.

Anab Ovidie Grand (NUPI) and Kheira Tarif (SIPRI) both support a collaborative project undertaken by NUPI and SIPRI to generate evidence-based information on a select number of countries on the UN Security Council agenda. The Climate Change, Peace and Security Fact Sheet on Somalia is available here.