Globally, prisons are understood to be crucibles, hosting, accelerating and spreading disease generally because of overcrowding and associated unsanitary conditions. When COVID-19 emerged in late December 2019, there was a united reaction towards isolating the world’s estimated 10.7 to 11 million prisoners from having contact with their nations’ outside populations.

When the novel COVID-19 appeared on the continent in February 2020, countries reacted almost in unison towards containment, isolation and preventing spread into society, while launching parallel efforts to eradicate the pandemic within prison facilities.

Tweet

On the African continent, 53 countries account for 1.1 million prisoners, outside of the unknown figures from Somalia and Eritrea. The environment of African prisons has been regarded as almost universally poor, with serious neglect towards alleviating overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. This view is reinforced by the African Union Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (AUCHPR), which has pointed out: “Conditions of prisons and prisoners in many African countries are afflicted by severe inadequacies including high congestion, poor physical, health, and sanitary conditions, inadequate recreational, vocational and rehabilitation programmes, restricted contact with the outside world, and large percentages of persons awaiting trial, among others (sic).”

When the novel COVID-19 appeared on the continent in February 2020, first in Egypt and then in Algeria in the same month, countries reacted almost in unison towards containment, isolation and preventing spread into society, while launching parallel efforts to eradicate the pandemic within prison facilities. From March through to May 2020, a discernible three-pillar strategy evolved towards guiding the continent’s counter-preventative response. In the first instance, states issued instructions to the judiciary, acting under disaster management and emergency laws, “ordering judges to avoid sentencing people to prisons ‘at all costs’ in order to prevent coronavirus spread.” The intention was to freeze numbers in the prisons while urgent efforts were launched to deal with a preferred static community. This is important as in the prison cycle, thousands of inmates either on remand or sentenced by the courts enter prisons, while at the same time, thousands are released and rejoin society.

Guiding the management of inmates on the African continent are the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules), revised and adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in December 2015.

It is interesting to briefly review the debate that ensued between various states and stakeholders leading to the decision to decongest prisons during the initial period of responding to COVID-19. This understanding is important in guiding the subsequent new policies in particular, as the continent is confronted with an even greater threat than that witnessed in February associated with the possible spread of COVID-19 from prisons.

To this end, on 26 March in Nigeria, the interior minister called for a “massive decongestion of the country’s prisons” to prevent the spread of COVID-19. State governors were advised to visit prison establishments to identify detainees eligible for release. In Nigeria, the statistics showed that 42% of prisoners were on remand and should be considered a priority for release. In South Africa, three organisations played a role: there were submissions from prosecutors to impose a freeze by the judiciary in processing prisoners, as the correctional services department was perceived as failing to cope in transporting the numbers. Second, two other civic organisations also weighed in: the South African Prisoners Organisation for Human Rights (SAPOHR) and the South African Sentenced and Awaiting Trial Prisoners Organisation (SASAPO) both argued against the 19 000 prisoners whom the government had decided to release, and instead called for a minimum of 24 000 prisoners to be released. This would then significantly reduce the total prison population to about 120 000. In Malawi, the Chilungamo Programme – whose aim is to make it easier to relieve overcrowding in the country’s prisons by promoting sentencing adjustments – made special appeals to the state for increased numbers to be released, rather than a miniscule 1 397 prisoners. In Cameroon during May, the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners (CL2P) stated that a “large number” of prisoners had already tested positive for COVID-19, and requested the government to release significantly more than the 7 000 freed out of a total of 29 341 prisoners. Finally, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Bill Clinton Foundation for Peace (BCFP) pressured the government to speed up the release from the estimated 20 000 rather than the 2 500 offered amnesty.

Ultimately, governments agreed to release inmates aged over 60 years, those that have served their sentences with only three years remaining and have been exemplary inmates, those living with disabilities, and those who had committed non-violent crimes. What is clear from this sampling survey is that governments commonly decided on conservatively smaller numbers against the higher submissions of civic and professional stakeholders.

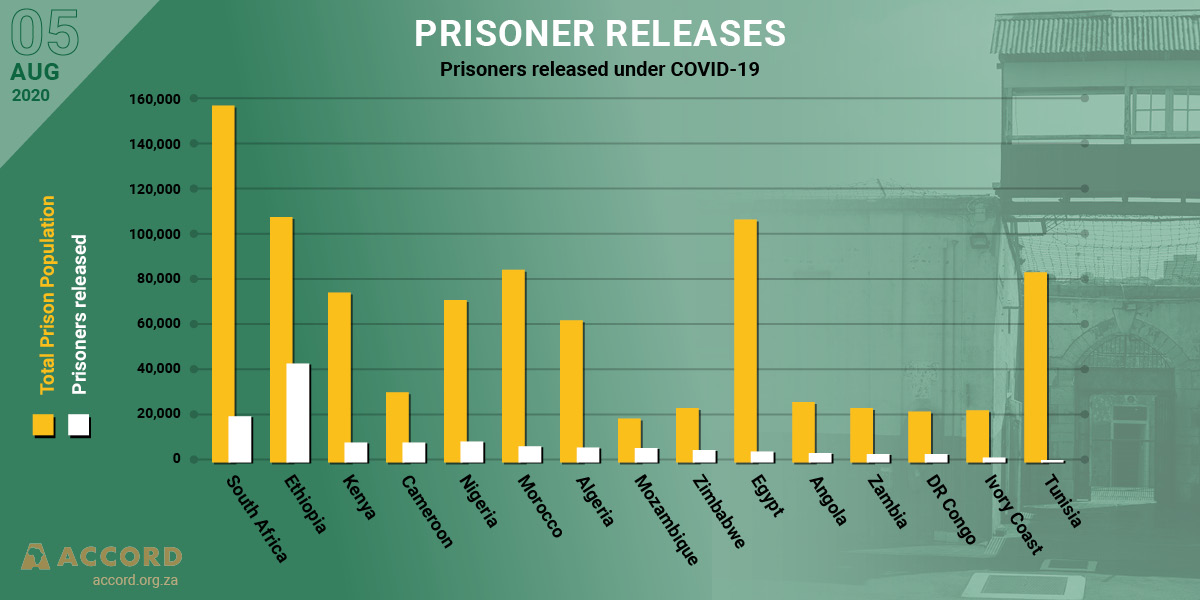

The table below shows the 15 African countries with the highest number of prison inmates released, when the decisions were taken against the total prison population in each country.

| Country | Prisoners released | Date | Total prisoner population |

| South Africa | 19 000 | 10 June 2020 | 158 111 |

| Ethiopia | 41 560 | 6 May 2020 | 113 727 |

| Kenya | 7 000 | 11 May 2020 | 74 000 |

| Cameroon | 7 000 | 23 June 2020 | 29 341 |

| Nigeria | 7 813 | 7 July 2020 | 73 631 |

| Morocco | 5 654 | 20 May 2020 | 85 767 |

| Algeria | 5 037 | 20 May 2020 | 61 000 |

| Mozambique | 5 032 | 6 April–4 June 2020 | 19 832 |

| Zimbabwe | 4 208 | 1 May 2020 | 22 000 |

| Egypt | 4 011 | 23 April 2020 | 106 000 |

| Angola | 2 997 | 20 May 2020 | 24 000 |

| Zambia | 2 528 | 22 May 2020 | 22 823 |

| DRC | 2 500 | 23 April 2020 | circa 20 550 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2 004 | 6 April 2020 | 21 186 |

| Tunisia | 1 428 | 31 March 2020 | 82 663 |

Sources: Prison Insider; https://www.prisonstudies.org/map/africa [accessed 30 July 2020].

The new threat – the virus is out of the confines of African prisons

There is evidence showing that the initial strategy to contain, isolate and prevent the spread of COVID-19 in and from African prisons as part of national efforts towards flattening the curve has failed. Alarming confirmation of the presence and rapid acceleration of COVID-19 within and from prisons started emerging from civic and stakeholder comments before the official confirmation of prison warders themselves becoming infected with COVID-19. For instance, in South Africa – which holds the largest number of prisoners on the continent and where statistics are published and updated daily on the correctional services department website – figures showed that at the beginning of August 2020, a significant 3 389 correctional services officials had been infected against 1 753 inmates, giving a total of 5 142 cases within the prisons. A more broad assessment therefore indicates that in the interim, prisons are likely to be understaffed, which raises concerns about the security and health of prisoners.

Furthermore, the effect of those infected prisoners continuing to spread the virus within the prisons, as well as contaminating those visiting the facilities, needs to be considered. And finally, new prisoners continue to enter prison facilities while others continue to be released at the end of their sentence and rejoin society. These discharged prisoners may be asymptomatic – and may unknowingly pass the virus onto others. In total, the African prison system may now be playing the exact role that was feared and which governments sought to prevent in March 2020.

A new strategy is required, based on evaluating the factors considered in phase one and the context of the new threat, and appropriate countermeasures then need to be developed. The new strategy will necessarily have to be built on the foundations of the Nelson Mandela Rules of December 2015. However, beyond this, policy frameworks have been produced from which guidance may be selected. These include the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidance on preventing COVID-19 outbreaks in prisons; the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) position paper on COVID-19 preparedness and responses in prisons; and finally, the Penal Reform International briefing note on coronavirus: Healthcare and Human Rights of People in Prison. There must also be engagement with national civil society organisations, whose understanding of local characteristics remain central in identifying the specificities of each country to achieve the appropriate strategy required to contain, isolate and prevent COVID-19 from exiting African prisons, while caring for the inmates’ welfare. Lastly, a balance has to be reached between exacting penal sentencing and the challenge to respond to public a health crisis as it relates to the dynamics of imprisonment.

In conclusion, it is imperative that governments consider the need to decongest prisons through a number of measures to ensure the human rights of prisoners and to further limit the spread of coronavirus to the outside population. Prisoners, after all, are afforded rights, and theirs should not merely be discarded because of a criminal record. The era of COVID-19 is unprecedented and offers an opportunity to manage prison populations on the continent in a different but innovative manner.