Introduction

Prior to the advent of so-called scientific knowledge and systems, indigenous knowledge was the single-most important aspect of human development utilised by communities across the world to sustain their well-being. With the advance of technology, indigenous knowledge is often mistakenly labelled as unscientific, illogical, irrational, traditional and a development impediment.1 Such conceptions of indigenous knowledge resulted in the favouring of scientifically driven approaches, which are mainly Eurocentric, as the main solutions to the development–democracy challenges of underdeveloped nations. Indigenous knowledge is also usually viewed as valueless to sustainable development. Consequently, newly independent states in Africa, South America and Asia have followed the adoption of a “one-fits-all” approach to development.

Unfortunately, the adoption of foreign-born and -grown development and democracy models without integration into indigenous development and values creates political and development uncertainties in Third World countries. Policymakers and development planners have thus failed to achieve sustainable development. A dependency syndrome of developing states on Western fabricated development models has thus emerged.

Nevertheless, the last three decades have witnessed a paradigm shift from the total sidelining of indigenous knowledge to the importance of promoting, empowering and linking it to solutions. A new area of interest is indigenous natural resource management mechanisms. As mentioned previously, conservationists and policymakers downgraded indigenous resource management mechanisms. According to Zelealem and Williams:2 “[R]ecent interest by conservationists in indigenous resource management systems, however, has arisen from the failure of many other types of conservation initiatives and the search for viable and sustainable alternatives to current models for managing resource use.”

In this regard, Ethiopia is very rich in indigenous knowledge systems, practice, knowledge creation (such as Qine), architecture, medicine, agriculture, cottage industry, conflict resolution, governance, natural resource management mechanisms, terracing experience (of the Konso people) and building (of houses from stone in North Shewa and Tigray). However, these indigenous knowledge systems and practices are not systematically identified, studied, documented and utilised in a manner that meets sustainable development goals and improves quality of life. The indigenous knowledge system in Ethiopia is an unseen, underutilised and neglected resource with incomparable potential for development.

One of the most effective (but neglected) and oldest communal property conservation mechanisms was the Qero system of Menz Guassa. Since the 17th century to the last quarter of the 20th century, local communities developed and used this sustainable natural resource management system. The Qero system allowed for the equitable use and distribution of natural resources (thatching grass, fuel wood and grazing) that were fundamental to the livelihood and security of the community. This article discusses community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) mechanisms, specifically the Qero system of Menz Guassa, from the perspectives of environmental governance and democratic values and principles.

Community-based Natural Resource Management Mechanisms

There are a variety of terms used to refer to CBNRM mechanisms, including participatory, community, community-based, collaborative, joint and popular natural resource management. CBNRM is an approach that evolved in the 1980s as a result of the failure of Western-born and -developed conservation models and paradigms in Third World countries. The main assumption is that development planners failed to achieve sustainable development and paradoxically created Western dependency. Therefore, communities found their own ways to survive by looking back to indigenous knowledge, which was “tried and tested, effective, inexpensive, locally available, and culturally appropriate; and in many cases [they] are based on preserving and building on the patterns and processes of nature”.3

There is no universal definition of CBNRM. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark4 uses the term CBNRM to denote “all kinds of approaches to managing natural resources that fit”. Roe5 viewed CBNRM from a local perspective as the management of natural resources such as land, forests, wildlife and water by collective, local institutions for local benefit. The definition given by Fabricius6 supports this, as he views CBNRM as the collective use and management of natural resources in rural areas by a group of people with a self-defined, distinct identity, using communally owned facilities.

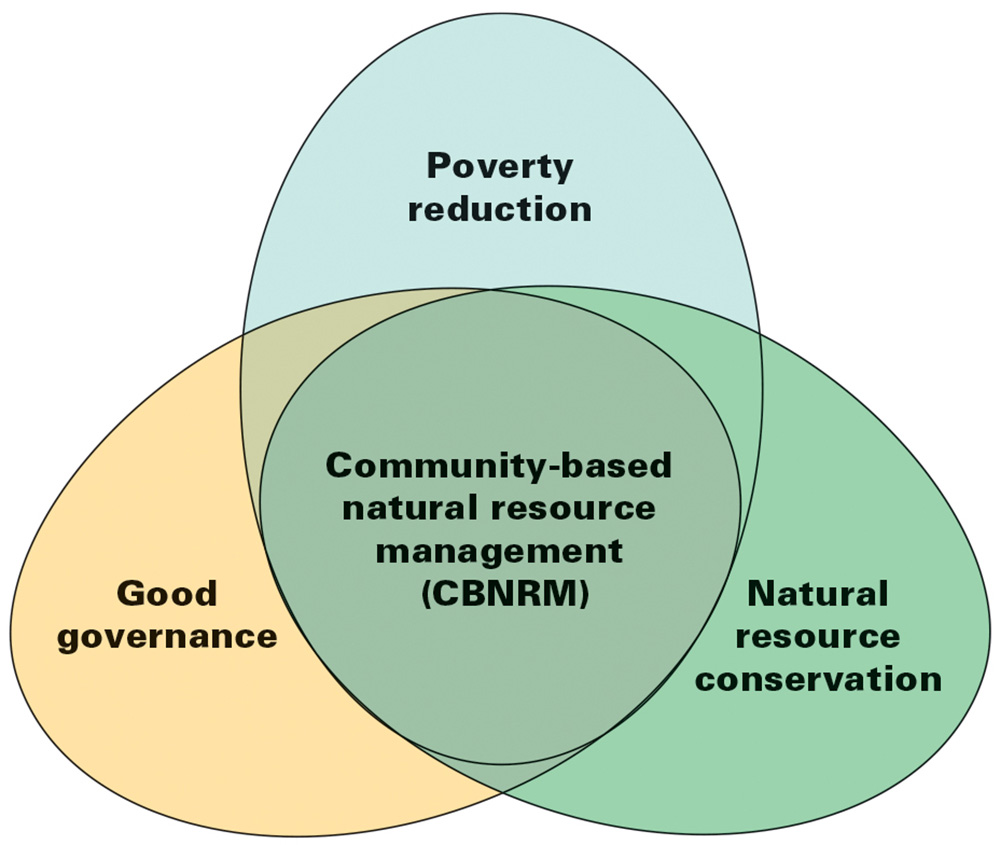

CBNRM has evolved in the last four decades to realise the sustainable use of natural resources, and that people living with the resources should be responsible for their management and should benefit from using these natural resources. CBNRM is a major global strategy for enhancing conservation outcomes while also seeking to improve rural livelihoods. CBNRM has a trinity of goals: poverty reduction, natural resource conservation and good governance. These goals have an overlapping, linked relationship. Since natural resources are the most important resources of communities, poverty alleviation is linked with natural resource use and conservation. However, natural resources are not abundant. Rather, they are scarce resources with uneven distribution; as a result, they are the source of competition and conflict among communities and nations. The socio-economic and political development of a given community is largely determined by access to these scarce resources. It is thus imperative to ensure the sustainable management and use of resources based on principles of equity, community participation and good governance. Governance is the ongoing process of good decision-making; in the contemporary world, decentralisation, inclusiveness, equity, equality and responsiveness have been increasingly acknowledged as the fundamental elements of good governance.

Figure 1: CBNRM goals7

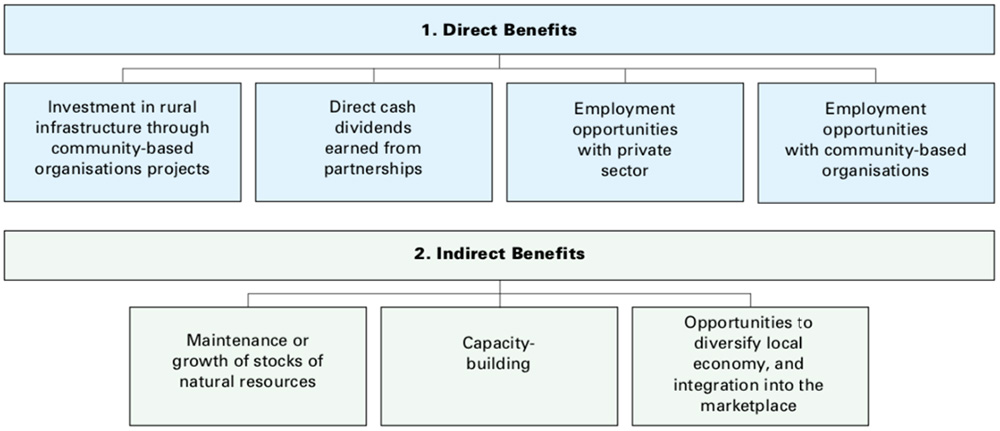

The major principles of CBNRM include being people-focused, being participatory, being holistic, building on strengths, using a partnership approach, being sustainable and being dynamic. CBNRM has become the dominant conservation and development paradigm in the post-1980s, with financial and non-financial benefits8 as outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Benefits of CBNRM9

There are several CBNRM mechanisms that are unique and dynamic to a given community’s physical environment. The Menz Guassa Community Conservation Area is one of the oldest and most recognised common property resource management areas in sub-Saharan Africa. According to Zelealem:10

Ethiopia is home to one of the oldest, most effective conservation management systems in sub-Saharan Africa, the Menz-Guassa Community Conservation Area, an 11,100-hectare region that is home to a rich endowment of grasslands, plants and rare animals such as the Ethiopian wolf, gelada and Abyssinian hare. The history of the indigenous land tenure system known as Atsme Irist reveals a great deal about how people in Menz have been able to regularly use, but also preserve, valuable grazing lands and ecosystem services for more than 400 years.

The Menz Guassa Community Conservation Area

Menz Guassa, at the heart of the Shewan plateau, is home to many endemic but classified endangered plant and animal species as a result of the existence of the Qero indigenous conservation system for more than 400 years. The area has variety of names, including Menz Guassa, Guassa plateau, Menz Guassa Community Conservation Area and Ye Gera ena Asebo Serge. The name “Guassa” is derived from the grass Festuca abyssinica, locally known as Guassa grass. Menz Guassa is found in the north-eastern part of the regional state of Amhara Region.

According to Amhara regional state council regulation No. 97/2012,11 Menz Guassa is found in the Menz Gera Midir woreda (district), covering a total area of 7 800 hectares of land. It shares boundaries with the Lulgie-Seret and Meskel Ber kebeles (neighbourhoods) of the Efrata Gedem woreda to the east, as well as the kebeles of the Menz Gera Midir woreda to the west, north and south. It is a source of more than 26 rivers and is a sanctuary for endangered wild animals, plants and birds that are endemic to Ethiopia, including the Ethiopian wolf, gelada, Abyssinian hare, Abyssinian meadow rat, unstriped grass rat and shrew, and various endemic birds.

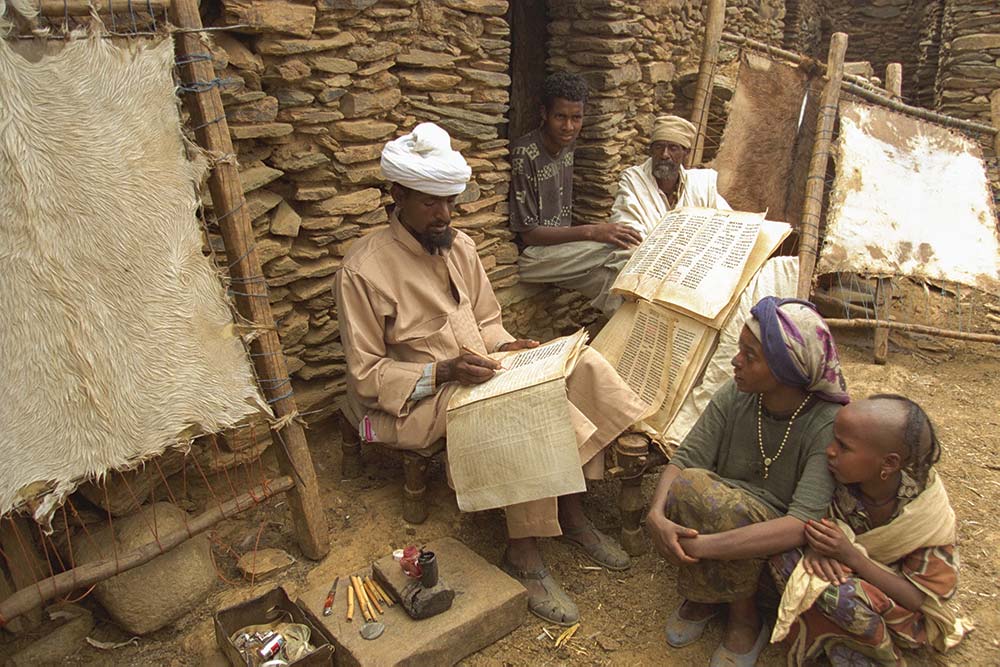

The communities in the surrounding areas of Guassa created an indigenous conservation system in the 17th century known as the Qero system. According to oral sources, this system was founded by the pioneer fathers, Asbo and Geralocally called Aqgni Abat), who were claimed to be the sons of Abeto Negasi Krestos, founder of the Shewan dynasty. Gomeje12 indicates how the Qero system evolved:

The two brothers also evolved their own traditional administration system called Qero and Afero. Qero refers to men specially who are physically strong and have a militia experience and Afero refers to women and children who are considered as weak. The Afero serves to protect the area from cattle grazing and referring them to the Qero and Qero plays the main role in protecting the area forcefully and taking measures. Qere derived from the local word Qre/ ቅ ሬ , a traditional institution which serves the community during the time of death and funeral ceremony. The head of the Qere is called Aba Qere and those who are assigned to lead the system. Aba-Qere was selected from the royal family, because they had time to visit the place since they were not busy by caring production and other activities as the remaining community member. According to key informants, the last two Qere’s of the study area based on the indigenous administration system were Ato Sheresher Wolde from Gera and Ato Demeke from Asebo.

The Qero system was practised by choosing a headman, called an Aba Qero or Afero, who is responsible for protecting and regulating use of the Guassa area. The Asbo and Gera areas each had one Aba Qero (Afero). The Aba Qeros were mostly elected unanimously in the presence of all users of the common property and resource. According to Zelealem and Williams:13

The user communities of the Guassa were further subdivided at a Tabot or Mekdes (parish) level. The Asbo users were organized under six parishes, while Gera users were organized under eight parishes. Each parish had one headman esquire (Aleqa or Chiqa-shum) who was answerable to his respective Abba Qera.

Under the Qero system, the Guassa area was protected from all types of interference – at least for a period of three to five years – until the Aba Qero/Afero announced before a church assembly to the legitimate users to use the Guassa grass for whatever purpose, to collect fuel wood and to graze livestock. The Aba Qero also allowed people to use the Guassa when there was drought and during the times when he believed that the grass had recovered enough. Starting from the announced date to 5 June of that year – locally known as Hamle Abo – the grass would be used. The grassland would then be closed on Hamle Abo.

The Qero System of Menz Guassa

The Qero system had its own rules and regulations that were followed by legitimate users. These included law-making and enforcing mechanisms to protect, manage and use the Guassa in a sustainable manner. The area was divided into two parts: Gera and Asbo, after the two brothers who founded the Qero system. Those who claimed to be descendants of Gera and Asbo used Gera and Asbo’s demarcated areas respectively. Each of the areas had one Aba Qero/Afero. Each Aba Qero/Afero was responsible for his respective area.

The two Aba Qeros also formed the Aba Qeros council – the highest decision-makers of the Guassa area. Gera’s area had six parish heads, while that of Asbo had five parish heads. Both areas also had a Yegolmasa Getoch, who was responsible for enforcing the rules and regulations of the Qero system. Aba Qeros/Aferos were chosen unanimously by the community, based on certain criteria, in the presence of all users of the common property resource. They were responsible for protecting and regulating the use of the Guassa area. The Qero system rules and regulations included:

- Gag rule: a rule that limited or forbade the users rights during a known period of time. The Guassa area is protected from grazing and any type of use by the community for consecutive periods, for as long as three to five years. This rule was known as yezig hig. The closure year was largely determined by factors such as drought frequency, users’ harvesting demands, recovery of the Festuca (Guassa) grass and local crop harvest.

- Users who claimed and traced their ancestors from Asbo or Gera had the right to use as much grass as needed during the open season of the Guassa grass, regardless of status, property and prestige.

- Users were obliged to leave the Guassa area before Hamle Abo (5 June).

- Users and elected Yegolmasa Getoch were required to strictly follow all rules and regulations of the system. Any violation resulted in harsh punishments, such as burning, beating and payments.

Enforcement Mechanisms

The Qero system had its own law-enforcing mechanisms to protect the common property resource, which was described by the people as “Libsachin and Gursachin”, meaning “Guassa is our shelter and food”. It had three law-enforcing mechanisms: the entire community, Yegolmasa Getoch and Aba Qeros. First, the entire community together had a responsibility to protect their common property. Second, Yegolmasa Getoch were the chosen law enforcers. The Aba Qeros frequently followed up and supervised their respective areas with these household heads, on dates chosen by the Aba Qeros. According to Zelealem and Williams:14 “[E]very able male household head was obliged to go out on patrol, and failure to participate would result in severe punishment for absentees. In some instances, punishment could result in burning down of the absentee’s house.”

Third, the Aba Qeros were also responsible for enforcing the rules and regulations of the Qero system. The Aba Qeros’ responsibility in general included:

- taking measures against those who violated the regulations in a respective area;

- determining whether the Festuca (Guassa) grass was ready for harvest or not;

- announcing the opening date of use for the legitimate and rightful owners of the Guassa community at the church assembly, local marketplaces and funeral ceremonies, such as Qire. The opening day was announced by the senior Aba Qero after he received the blessing of an elder priest; and

- examining drought frequency, the users’ harvesting demand, the recovery of the Festuca (Guassa) grass and the local crop harvest particularly during the belg (rainy season).

Different punishments were meted out when rules were not followed. These punishments were often very harsh.

Democratic and Environmental Governance Principles and Values within the Qero System

The Qero system had democratic and environmental governance values and principles. On the one hand, the Qero system was a direct, participatory democracy – Aba Qeros were directly chosen by the community, based on certain criteria. On the other hand, it was also a conscious democracy model as it had law-making, enforcing and decision-making institutions. The community, headed by the Aba Qeros, developed rules and regulations, and the Yegolmasa Getoch were responsible for law enforcement. Aba Qeros could also take appropriate measures against violators.

Democratic Election of Aba Qeros/Aferos

The Qero system was headed by directly chosen Aba Qeros/Aferos. According to Zelealem and Williams,15 the Aba Qeros were mostly elected unanimously, in the presence of all users of the common property resource.

Sustainable Natural Resources Conservation System

The other environmental governance value found within the Qero system was sustainability. The system was based on the principle of sustainable biodiversity conservation. In Ethiopia, various government-owned and -protected parks are vulnerable to fire and destruction. However, there is no recorded history of the destruction of the Guassa area. This is attributed largely to the Qero system that prevailed, which ensured the sustainable availability of Guassa grass and its associated resources.

Equality of Use and Equity

The Qero system was founded on the principles of equality and equity. For equality to prevail, the first step was to recognise the equal rights of users. The second step was to ensure the equal utilisation of available resources. In this regard, the Qero system recognised the equal rights of each user, and had rules and regulations based on equity. The community, as descendants of Asbo and Gera, had full unconstrained rights to use the Guassa grass for whatever purpose they required during the permitted open season, regardless of the position, status and property they had. Rich and poor users had equal rights.

Acceptable Communal Conservation System

The Qero system was a communally accepted institution. For any system to be democratic, it must have the free consent of the populace. In this regard, the Qero system was an institution based on the free consent and unwritten covenant of the Asbo and Gera communities.

Conclusion

The Qero system was an effective, indigenous, communal natural resource conservation mechanism in Ethiopia. It was in effect until the 1974 revolution, after which it declined due to the sociopolitical changes taking place in the country. The Qero system had modern environmental governance values and principles such as sustainability, equality, equity and participation. Moreover, it was a direct and conscious democracy model, with values such as free consent of the community, the democratic election of Aba Qeros/Aferos, representation of the community and recognition of users’ full rights. What made the Qero system successful was the existence of rules and regulations, with enforcing institutions. The Qero system had a dual function: on the one hand, it was a natural resource conservation, protection and management mechanism, and on the other hand, it was a mechanism of community livelihood. The Qero system showed that there is an imperative to indigenise government conservation mechanisms and policies. While it is unlikely that the Qero system will be revitalised in modern-day Ethiopia, it is important to realise that local conditions and interests must be considered when mechanisms are developed to protect and manage communities.

Endnotes

- Kaya, Hassan O. and Matowanyika, Joseph Z.Z. (2017) ‘The Value of African Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Community-based Climate Observation Practices and Synergies with Climate Information Services in Africa’. Paper presented at the WISER Knowledge Management and Communication Workshop, 24–26 May 2017, UNECA/ACPC, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Available at: <https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/images/day_3_-_joseph_matowanyika_the_role_of_indigenous_knowledge_in_cis_knowledge_management_strategies.pdf> [Accessed 5 August 2019].

- Zelealem, Tefera Ashenafi and Williams, N. Leader (2005) Indigenous Common Property Resource Management in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Human Ecology, 33 (4), pp. 539–562.

- Grenier, Louise (1998) Working with Indigenous Knowledge: A Guide for Researchers. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark (n.d.) ‘Community Based Natural Resource Management’, Available at: <http://www.netpublikationer.dk/um/8283/html/printerversion_chapter01.htm> [Accessed 1 June 2019].

- Roe, Dilys (2011) Community-based Natural Resource Management: An Overview and Definitions. In Abensperg–Traun, Max, Roe, Dilys and O’Criodain, Colman (eds) The Relevance of CBNRM to the Conservation and Sustainable Use of CITES-listed Species in Exporting Countries. Vienna: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, p. 18.

- Fabricius, Christo (n.d.) ‘Community-based Natural Resource Management. Management of Agricultural, Forestry, and Fisheries Enterprises’, Available at: <https://www.eolss.net/sample-chapters/C10/E5-15-01-01.pdf> [Accessed 1 June 2019].

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark (n.d.) op. cit.

- Pailler, Sharon, Naidoo, Robin, Burgess, Neil D., Freeman, Olivia E. and Fisher, Brendan (2015) Impacts of Community-based Natural Resource Management on Wealth, Food Security and Child Health in Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 10 (7), pp. 1–22.

- World Wide Fund for Nature (2006) Community-based Natural Resource Management Manual. Wildlife Management Series, p. 8.

- Zelealem, Tefera (2016) ‘The Resilience of an Indigenous Ethiopian Commons’, Available at: <https://www.twn.my/twnf/2016/4449.htm> [Accessed 3 June 2019].

- Regulation No. 97/2012, The Amhara National Regional State – the Menz Guassa Community Conservation Area Boundary Demarcation and Administrative Determination, Council of Regional Government Regulation.

- Amessie, Gomeje (2014) Opportunities and Challenges of Community-based Natural Resource Management in Menz-Guassa Community Conservation Area, Ethiopia. Unpublished MA thesis, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, p. 29.

- Zelealem, Tefera Ashenafi and Williams, N. Leader (2005) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.