Introduction

The overthrow of Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir from the presidency of Sudan by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) on 11 April 2019, following several months of protests and civil uprisings by Sudanese citizens, resulted in a prolonged governance and political crisis. Al-Bashir, who was a SAF lieutenant general, came to power in June 1989, through a military coup d’état staged against Sadiq al-Mahdi, who was the then-prime minister of Sudan. Al-Bashir had been in power for almost 30 years, making him one of the longest-serving presidents on the continent. Following his ousting on 11 April 2019, internal political players and stakeholders – mainly the ruling Transitional Military Council (TMC) and a coalition of protesters and opposition groups, led by the Alliance for Freedom and Change/Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) in Sudan – failed to speedily agree and settle on an effective transitional governance authority.

However, following different forms of interventions from regional and international actors and players, the TMC and FFC finally signed the Political Agreement on Establishing the Structures and Institutions of the Transitional Period between the Transitional Military Council and the Declaration of Freedom and Change Forces, on 17 July 2019. Subsequently, on 17 August 2019, the TMC and FFC signed the Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period – widely referred to as the Constitutional Declaration – which replaced the Transitional Constitution of Sudan of 2005. This Constitutional Charter is set to be in force for a 39-month transitional period.

The new prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, was sworn in on 21 August 2019. He appointed his Cabinet of Ministers on 5 September 2019, within the framework of a power-sharing agreement between the military, civilian representatives and protest groups. With a civilian-led government now in place in Sudan, ready to preside over governance in the set transitional period, it is time to reflect on the role of regional and international interventions in resolving the post-coup crisis in Sudan. This article therefore assesses the role played by external actors and players in resolving the post-coup crisis in Sudan, specifically evaluating the accomplishments and setbacks encountered in assisting the parties to fully agree on transitional governance mechanisms. This reflection will assist in understanding the evolving role of regional and international institutions in African conflicts, and their sustainability and broader implications on the continent. The article focuses on the main influential external actors, which include the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Ethiopia (under the Ethiopian Initiative), the African Union Commission (AUC), the Arab League, the Sudan Troika (of the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Norway) and the United Nations (UN).

The Sudan Crisis: Background and Context

Politically, Sudan has a history and political culture of many coups, having experienced these in 1958, 1969, 1985 and 1989, as well as failed coup attempts in 1961 and 1971.1 This lack of consistent, orderly and smooth transfer of power in most of Sudan’s transitions signals deep-rooted and entrenched governance challenges. The country has endured long periods of bloody conflicts and war, interrupted by short periods of peace, since attaining political independence in January 1956. In Sudan: The Elusive Quest for Peace, Ruth Iyob and Gilbert Khadiagala fittingly make reference to Sudan as “a land where peace always seems to hover on the horizon while numerous destructive wars scar its inhabitants”.2

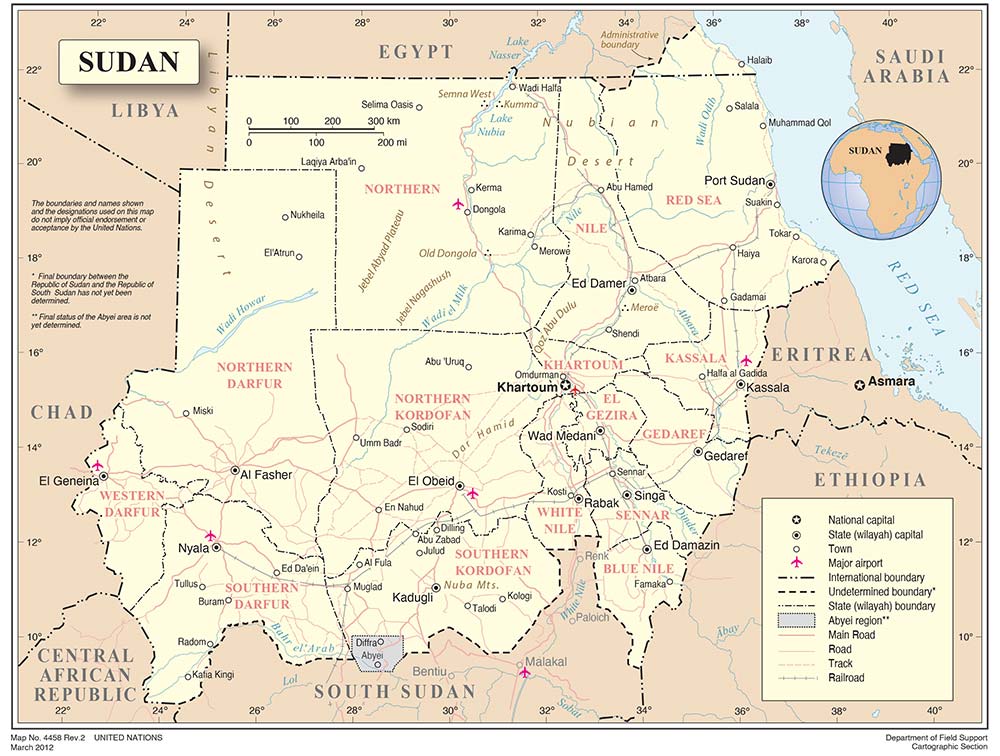

Sudan’s First Civil War (1955–1972) and the Second Civil War (1983–2005) were both motivated by different political, historical, social and economic grievances. These included the clamour for autonomy by the southerners, driven by disgruntlement over regional imbalances, under-representation, exclusion, inequality, exploitation and marginalisation of southerners, unequal access to scarce resources, misgovernance and the curtailment of freedoms and civil liberties on the basis of regionalism, religion, ethnic groupings and political affiliation.3 This ultimately led to the secession of South Sudan in July 2011, following an overwhelming affirmative vote through a referendum in southern Sudan in January 2011. Despite the secession, Sudan continued to experience internal latent conflict, with full-blown conflict in Abyei and South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, mainly due to outstanding issues that emanated from the pre-secession agreement – that is, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of 2005, specifically the Protocol on the Resolution of the Conflict in Abyei Area and the Protocol on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile States, both signed on 26 May 2004 by the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). On the other hand, Sudan also experienced destructive genocidal conflict in the Darfur region from 2003, involving the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebel groups against the government of Sudan, sparked by tribal disputes over access to land and water. This war led to warrants of arrest for al-Bashir in March 2009 and July 2010 by the International Criminal Court on allegations of crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of genocide.

Economically, Sudan has not managed to deliver consistent and inclusive socio-economic development and growth since independence, despite having huge oil reserves and with the country ranked among the top five largest oil producers in Africa before secession.4 The country is also rich in iron ore deposits, copper, mica, zinc, chromium ore, silver, tungsten and hydropower. Over and above the destabilising effects of conflict, failure to diversify the economy and implement effective macro-economic management has led to retarded growth and development in Sudan since independence. In addition, United States (US) sanctions on Sudan, issued under Executive Order 13067 of 3 November 19975 and Executive Order 13400 of 26 April 2006,6 imposed a trade embargo on Sudan and blocked the property of certain people over allegations of supporting international terrorism, destabilising neighbouring governments, human rights violations and threatening the national security and foreign policy of the US. Further, the secession of South Sudan resulted in a loss of oil revenue that accounted for over 50% of government revenue and 95% of its exports; all this was made worse by the 2015/2016 global oil price slump.7 By 2017, Sudan was afflicted by high inflation of over 55%, trade and financial sanctions, persistent fiscal and external trade deficits, higher energy prices, debt distress and macro-economic instability.8

Whilst the previous discussion highlights the background to the Sudanese conflict, the immediate cause of the eruption and escalation of the 2018/2019 protests was the rising cost of living, and the trigger was the disorder caused by the tripling of bread prices and an increase in the fuel price on 19 December 2018.9 These protests started in the town of Atbara and spread to Port Sudan, Dongola and Khartoum, with the protesters ultimately demanding economic transformation, political reforms and the stepping down of al-Bashir. The reaction and response from the government – declaring a state of emergency; dissolving the government and appointing military and intelligence service officers; using excessive force; as well as arresting, incarcerating and torturing protesters – incited more protests. The protests finally led to al-Bashir’s ouster by the SAF on 11 April 2019, before he was transferred from house arrest to prison on 17 April 2019 and charged for political killings on 13 May 2019. The TMC, led by Lieutenant General Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf (who had been the country’s Minister of Defence since 2015), took over after dissolving Cabinet and Parliament, before Ibn Auf stepped down and was replaced by Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan. Continued protests by citizens since then – organised by the Sudanese Professional Association and other opposition groups calling for a civilian transitional authority – have been brutally suppressed by the TMC security forces and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), along with shutting down the internet to disable and disrupt social media protest mobilisation, and with hundreds of people having been injured and killed.10

The TMC and the FFC finally reached agreement and signed the Political Agreement on 17 July 2019, and later the Constitutional Declaration on 17 August 2019 – which will both facilitate the sharing of power in the transitional period of three years before elections are conducted. These signings paved the way for the appointment of the Sovereign Council on 21 August 2019, led by General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan, who was also the leader of the TMC. The Sovereign Council is a 11-member joint ruling body that officially dissolved and replaced the TMC. It is made up of five members of the military chosen by the TMC, five civilians chosen by the FFC, and a civilian jointly chosen and agreed on by both the TMC and the FFC, as provided for under Article 10 (2) of the Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period.11 It is the highest authority in Sudan, although it delegates executive powers to the Cabinet of Ministers, led by Hamdok.

The Context and Traditional Basis of External Intervention in Conflict

Before exploring the role of external players in managing the post-coup crisis in Sudan, it is necessary to understand the context and basis upon which external actors get involved in the management and resolution of conflicts within their region. External players are empowered by various aspects of international law to intervene in conflicts.

One of the African Union’s (AU) principle objectives, provided under Article 3 (f), is to “promote peace, security, and stability on the continent”.12 The AU is empowered to intervene in any member state on the strength of Article 4 (h) of the Constitutive Act of the continental body, which provides “the right of the Union to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity”.13 Thus, interventions to promote peace, security and stability take different forms, such as diplomatic efforts, facilitating negotiations, mediation, dispute resolution or exerting political pressure, and so on. However, it is a sacrosanct principle that the sovereignty of member states is respected.

Within the context of Sudan, IGAD is a key regional organisation. In its preamble, the Agreement Establishing the IGAD affirms the desire by member states to promote “peace, security and stability, and eliminate the sources of conflict as well as prevent and resolve conflicts in the region”.14 IGAD member states commit to the peaceful settlement of interstate and intrastate conflicts through dialogue, as well as the maintenance of regional peace, stability and security. In preventing, managing and resolving conflicts at the regional level, regional organisations such as IGAD are guided by Chapter VIII on Regional Arrangements of the UN Charter of 1945 as the enabling law. Article 51 of the Charter encourages regional organisations to engage in pacific settlement of local disputes, either on the initiative of the states concerned or by reference from the UN Security Council.15 Regional organisations thus have interests even in intrastate conflicts, as these may spill beyond borders and threaten regional – and, consequently, international – peace, security and stability.

There has been much debate in international law about the norms governing the basis of intervention in intrastate conflicts by states in their individual capacity. However, this intervention is often based on the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) obligation – that individual states and the international community must take appropriate action in a timely and decisive manner in accordance with the UN Charter if there are situations where populations are at risk of crimes against humanity, war crimes and ethnic cleansing. This principle emanated from the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty Report of 2001 and was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2005.16 It should be stated that the R2P principle is usually argued to be at odds with the principle of state sovereignty.

The Role of Regional and International Actors in Managing the Post-coup Crisis in Sudan

The most influential external actors in Sudan were IGAD, Ethiopia (under the Ethiopian Initiative), the AUC, the Arab League, the Sudan Troika and the UN. Negotiations between the TMC and the FFC were complicated by a lack of compromise on both sides, an impasse over the proposed transitional arrangements and composition of leadership of the Sovereign Council, and repeated interruptions due to violence and killings directed at protestors in Khartoum and other cities that clamoured for civilian rule.

Inter-Governmental Authority on Development

Following the ouster of al-Bashir from the presidency of Sudan on 11 April 2019, as citizens protested against the imposition of military rule, the IGAD Council of Ministers made a commitment, at the regional bloc’s 68th Extra-Ordinary Session on 19 June 2019, to “bring all actors in the Sudan together for the resolution of their differences and to ensure an all-inclusive, Sudanese-led process and outcome that remedies the situation in the Sudan”.17 At the same meeting, IGAD made a decision to “assume a leading role to coordinate all efforts to bring sustainable peace in Sudan”, as well as to “coordinate its efforts with the Special Advisor of the Chairperson of the AUC”,18 consistent with the subsidiarity principle to ensure coherence and synergy, whilst calling on the international community to support the IGAD initiative.

In addition to coordinating the efforts of the AUC Special Envoy to Sudan, IGAD also contributed to addressing the Sudanese crisis by condemning violent acts of the TMC towards protesters, especially the 87 people reportedly killed and 168 wounded by security forces on 3 June 2019.19 In the process, IGAD played the lobbying and advocacy role, urging “all actors” in Sudan to “refrain from any act of violence” whilst working towards a lasting solution for an inclusive transitional government. IGAD also made a statement against interference by foreign players in the Sudan crisis.20

The African Union

The AU played a more visible and impactful role in addressing the post-coup crisis in Sudan. One of the boldest and most decisive actions, taken on 6 June 2019 by the AU, was to suspend Sudan from participating in all AU activities. This was a decision of the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) at the 854th Meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in line with the AU Constitutive Act and African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, specifically Article 7 (1) (g) of the Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union, which provides that the PSC may “institute sanctions whenever an unconstitutional change of Government takes place in a Member State, as provided for in the Lomé Declaration”.21 The readmission condition was that Sudan needed to establish a civilian-led transitional authority.

Prior to this decision, the AU visited Sudan to assess the situation and consult with key stakeholders to identify a lasting solution to the crisis. For example, the chairperson of the AUC, Moussa Faki Mahamat, visited Khartoum on 20-21 April 2019 and had consultations with the TMC, political parties, civil society organisations, the UN, European Union (EU), bilateral partners, African diplomatic corps and other members of the international community.22 In addition to this, the AU chairperson, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi of Egypt, convened a Consultative Summit of the Regional Partners of The Sudan on 23 April 2019. This was attended by 12 member states (Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan and Uganda) to contribute to a solution to the post-coup crisis in Sudan.23

The AUC also deployed Mohamed El Hacen Lebatt (principal strategic advisor to the AUC chairperson) on 1 May 2019 as the AU Special Envoy leading the AUC facilitation team, with the mandate to facilitate and technically support the negotiations and dialogue among the Sudanese stakeholders to reach a common agreement that would pave the way for a consensual and civilian-led transition.24 Other than facilitating negotiations, the AU Special Envoy assisted in exerting pressure on the parties to move speedily during periods of sporadic violence in June–July 2019; and also lobbied, through the AU PSC,25 for the launch of transparent investigations into the reported killing of protesters in June–July 2019 by RSF forces. In addition, just as was the case with IGAD, the AU added its voice to caution “foreign actors to refrain from interference” and instead support the Sudanese-led and -owned peace process.26

It is through these marathon AU-mediated negotiations, complemented by Ethiopia, that the TMC and the FFC finally signed the Political Agreement on Establishing the Structures and Institutions of the Transitional Period between the Transitional Military Council and the Declaration of Freedom and Change Forces on 17 July 2019, as well as the Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period on 17 August 2019.

The Ethiopian Initiative

Ethiopia’s involvement in the Sudanese crisis involved the country’s prime minister and his personal envoy. First, the prime minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, met Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan and members of the FFC in Khartoum on 7 July 2019 in an effort to foster dialogue. Later, a special envoy of the Ethiopian prime minister for Sudan, Ambassador Mohamoud Dirir, was dispatched to be part of the AU-brokered negotiations. However, there were concerns that the Ethiopian Initiative and the AU-led mediation were initially not well coordinated and synergised27 – to the extent that at one point during the course of the negotiations, the TMC expressed sharp criticism and displeasure against the approach, in favour of a joint initiative.28 However, this was later addressed as the negotiations proceeded, with the AU and Ethiopia eventually combining their efforts and proposals.

The Arab League

Given that Sudan is a member of the 22-member Arab League – a regional organisation formed in March 1945 by Arab states from the Middle East, North Africa and Horn of Africa – there were efforts from the Arab League meant to contribute to the peace process. On 16 June 2019, the Secretary General of the Arab League, Ahmed Aboul-Gheit, held talks with the TMC’s Burhan and FFC leaders in Khartoum, adding pressure for a civil government. However, the Arab League seemed not to have any tangible intervention or initiative to support negotiations other than encouragement for dialogue. Before the TMC–FFC negotiations resumed, an Arab League initiative led al-Sisi to meet the deputy head of the TMC, Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, on 29 July 2019 in Cairo, to discuss the security situation in Sudan. This led to insinuations that the Arab League favoured the TMC over the FFC. In August 2019, the Arab League issued a statement welcoming the signing of the Constitutional Declaration by the TMC and the FFC, reiterating its support of the transitional government.29

The United Nations, European Union and the Sudan Troika

The AU, as the leading facilitator of dialogue in Sudan, commended the collaboration of the UN, EU and the Troika of the USA, United Kingdom (UK) and Norway for the support they rendered to the mediation process.30 Since the beginning of the crisis in December 2018, the Troika issued several statements condemning the abuse of human rights and curtailment of freedoms, as well as the use of violence against peaceful protesters, whilst declaring its willingness to support dialogue and political and economic transition in Sudan.

The Troika also convened several meetings, attended by different stakeholders, to discuss the Sudanese crisis. For example, on 18 May 2019 and 21 June 2019, the Troika met in Washington DC and Berlin to discuss the post-coup crisis in Sudan. These meetings were attended by the Troika states, the EU, the AU, Germany, France, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Following the signing of the Constitutional Declaration, the Troika affirmed its commitment to support transitional processes in Sudan as well as economic, legal and constitutional reforms during the transitional period.31 By and large, the Troika has played a lobbying and advocacy role, using its historical influence in Sudanese politics.

On the other hand, the UN has been monitoring and assessing the situation in Sudan since the outbreak of demonstrations in December 2018, and engaged in preventive diplomacy to prevent the crisis from escalating. As such, it has issued statements strongly condemning the use of violence, rape, intimidation and excessive force by the TMC, and reminded the TMC of its responsibility to ensure the safety and security of citizens as well as protection of people’s freedoms, whilst also urging the protestors to exercise restraint.32 From the onset, the UN declared its willingness to support peaceful resolution of the conflict, inclusive dialogue and peaceful transition. During the course of negotiations, the UN encouraged the parties to agree on a settlement, and also pledged to support the transition process in Sudan after the signing of the Political Agreement and Constitutional Declaration, through legal, political and institutional reforms.33

Outcome of Interventions: Accomplishments and Setbacks

The various regional and international actors – namely IGAD, Ethiopia, the AUC, the Arab League, the Sudan Troika and the UN – contributed in different ways to address the Sudan crisis. IGAD, Ethiopia and the AUC were very active through facilitative mediation, whilst the other players were engaged more in preventive diplomacy to prevent the escalation of the crisis, as well as shuttle diplomacy to persuade the TMC and the FFC to engage in dialogue and reach a compromise agreement. The main setback was that the actors were not well coordinated, with each actor involved in its own initiative. However, IGAD, Ethiopia and the AUC ultimately engaged in a coordinated joint initiative. The major setbacks were the failure by the two parties in Khartoum to timeously reach a compromise, which was worsened by the heavy-handedness of the RSF in dealing with protesters, thus delaying negotiations. There were a few major accomplishments:

- the restoration of relative peace and stability;

- the success of the mediators in facilitating the signing of the Political Agreement and Constitutional Declaration;

- the readmission of Sudan into the AU;

- the ultimate formation of a transitional government; and

- the regaining of confidence in the transitional government by the international community.

Conclusion and Way Forward

There is no dispute that the role of regional and international actors is effective in addressing conflicts in Sudan and in the subregion. Although it is understandable that the various actors are motivated by different geostrategic, political and sometimes economic interests in their interventions, what is recommended is more cohesion and coordination of efforts in addressing conflicts in Africa. As the key player in regional conflict resolution and management, the AUC needs to have a clear template for being the interface between regional organisations to avoid uncoordinated and disjointed interventions.

Moving forward, it is also recommended that regional and international actors address the key priorities of the post-crisis phase in their support of the Sudanese Transitional Government by addressing the root causes of the crisis. These actors should also address the need for economic stabilisation, recovery and improving social service delivery; institute proceedings to investigate human rights abuses committed during the post-coup crisis; build strong and resilient institutions of governance; reform state institutions, including the security sector; and support initiatives to build sustainable peace across the country, including Darfur, especially at a time when the country is ranked as the eighth most fragile state in the world.34 Having said this, the success and effective delivery of the Sudanese Transitional Government is dependent upon the willingness of South Sudanese to work together harmoniously and constructively engage in the development of their own country. More importantly, the various actors that assisted in different ways to resolve the post-coup crisis in Sudan need to continue to invest efforts towards ensuring that the transitional government delivers its functions and mandate effectively. The Sudanese case presents vital and instructive lessons on how to facilitate and improve the efficacy of regional and international interventions during times of crisis and conflicts in Africa.

Endnotes

- Vhumbunu, Clayton Hazvinei (2018) Reflecting on the Root Causes of South Sudan Secession: What Can Other African Leaders Learn? Journal for Contemporary History, 43 (2), p. 154.

- Iyob, Ruth and Khadiagala, Gilbert M. (2006) Sudan: The Elusive Quest for Peace. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers Incorporated, p. 13.

- Vhumbunu, Clayton Hazvinei (2018), op. cit., p. 155.

- World Bank (2009) ‘Sudan: The Road Toward Sustainable and Broad-Based Growth’, p. 57, Available at: <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/337451468130798599/pdf/547180ESW0P07610public0distribution.pdf> [Accessed 19 November 2019]. See also: United States Energy Information Administration (2013) ‘Oil and Natural Gas in Sub-Saharan Africa’, p. 6, Available at: <https://www.eia.gov/pressroom/presentations/howard_08012013.pdf> [Accessed 19 November 2019].

- United States of America (1997) ‘Executive Order 13067 of November 3, 1997. Blocking Sudanese Government Property and Prohibiting Transactions With Sudan’. Federal Register, 62 (214), 5 November, p. 3, Available at: <https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Documents/13067.pdf> [Accessed 18 July 2019].

- United States of America (2006) ‘Executive Order 13400 of April 26, 2006 Blocking Property of Persons in Connection With the Conflict in Sudan’s Darfur Region’, Federal Register, 71 (83), 1 May, p. 1, Available at: <https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Documents/13400.pdf> [Accessed 18 July 2019].

- World Bank (2019) ‘The World Bank in Sudan: An Overview’, Available at: <https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/sudan/overview#1> [Accessed 19 July 2019].

- International Monetary Fund (2017) ‘IMF Staff Completes 2017 Article IV Visit to Sudan’, Available at: <https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/09/27/pr17373-imf-staff-completes-2017-article-iv-visit-to-sudan> [Accessed 20 July 2019].

- Gideon, Beny (2018) ‘Sudan After Ousting President al-Bashir: A Coup or Popular Uprising?’ The Sudan Tribune, 14 April, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article67372> [Accessed 21 July 2019].

- Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (2019) ‘Scores of Protesters Wounded and Seven Dead on Sudan’s Streets’, The Guardian, 1 July, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/30/fears-of-violence-as-sudan-gets-ready-for-million-man-march-khartoum> [Accessed 23 July 2019].

- Republic of Sudan (2019) ‘Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period’, p. 5, Available at: <http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Sudan%20Constitutional%20Declaration%20%28English%29.pdf> [Accessed 19 September 2019].

- African Union (2000) Constitutive Act of the African Union. Constitutive Act of the African Union Adopted by the Thirty-Sixth Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, 11 July 2000, Lomé, Togo, p. 5.

- African Union (2000), op. cit., p. 7.

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (1996) Agreement Establishing the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD). Assembly of Heads of State and Government, Nairobi, 21 March 1996, p. 4.

- United Nations (1945) Charter of the United Nations and Statute of the International Court of Justice. San Francisco, p. 11.

- United Nations (2005) ‘Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 16 September 2005 [without reference to a Main Committee (A/60/L.1)] 60/1’, 2005 World Summit Outcome, 24 October 2005, p. 30, Available at: <https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_60_1.pdf> [Accessed 22 September 2019].

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (2019) ‘Communiqué of the 68th Extra-Ordinary Session of IGAD Council of Ministers on Situation in the Sudan and the Status of the South Sudan Peace Process’, 19 June 2019, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, pp. 2–3, Available at: <https://igad.int/attachments/article/2155/07-01-19-Communique%20of%2068th%20Extra%20Ordinary%20Session%20of%20IGAD%20Council%20of%20Ministers.pdf> [Accessed 24 September 2019].

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Reuters (2019) ‘Sudan Says 87 Killed, 168 Wounded when June 3 Protest Broken Up,’ 27 July, Available at: <https://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFKCN1UM0BG-OZATP?feedType=RSS&feedName=topNews> [Accessed 28 September 2019].

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (2019), op. cit., p. 2.

- African Union (2002) ‘Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union’, 9 July, p. 9. Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37293-treaty-0024_-_protocol_relating_to_the_establishment_of_the_peace_and_security_council_of_the_african_union_e.pdf> [Accessed 19 November 2019].

- African Union (2019a) ‘Communiqué on the Visit of the Chairperson of the Commission to Sudan’, 21 April, Available at: <https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20190421/communique-visit-chairperson-commission-sudan> [Accessed 1 October 2019].

- Arab Republic of Egypt (2019) ‘President El-Sisi’s Closing Statement at Consultative Summit of Regional Partners of Sudan’, 24 April, Available at: <http://sis.gov.eg/Story/139654/President-El-Sisi’s-Closing-Statement-at-Consultative-Summit-of-Regional-Partners-of-Sudan?lang=en-us> [Accessed 2 October 2019].

- African Union (2019b) ‘Communiqué on the Dispatch to Sudan of a Mission to Support the Negotiations among the Sudanese Stakeholders’, 1 May, Available at: <https://au.int/ar/node/36556> [Accessed 3 October 2019].

- African Union (2019c) ‘Peace and Security Council 854th Meeting, 6 June 2019, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PSC/PR/COMM.(DCCCXLIV)’, p. 2, Available at: <https://archives.au.int/bitstream/handle/123456789/6386/850th%20Meeting%20of%20the%20AUPSC%20on%20the

%20Situation%20in%20Sudan%2c%206%20June%202019_E%20.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y > [Accessed 4 October 2019]. - African Union (2019d) ‘Statement of the Chairperson on Sudan Following Visit by IGAD Chair’, 8 June, Available at: <https://au.int/ar/node/36783> [Accessed 5 October 2019].

- Atta-Asamoah, Andrews and Mahmood, Omar S. (2019) ‘Sudan after Bashir: Regional Opportunities and Challenges’, Institute of Security Studies, East Africa Report, August, p. 2, Available at: <https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/ear-23.pdf> [Accessed 7 October 2019].

- Xinhua (2019) ‘Sudan’s Military Council Calls on African Mediators to Provide Joint Initiative’, 24 June, Available at: <http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-06/24/c_138167309.htm> [Accessed 8 October 2019].

- Al-Youm, Al-Masry (2019) ‘Arab League Welcomes Agreement between Sudan’s Military Council and Protesters’, Egypt Independent, 3 August, Available at: <https://egyptindependent.com/arab-league-welcomes-agreement-between-sudans-military-council-and-protesters/> [Accessed 8 October 2019].

- African Union (2019e) ‘AUC Chairperson Commends the Sudanese Stakeholder for the Progress being Made toward Reaching a Political Agreement’, 29 May, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/en/article/auc-chairperson-commends-the-sudanese-stakeholder-for-the-progress-being-made-toward-reaching-a-political-agreement> [Accessed 9 October 2019].

- Government of the United Kingdom (2019) ‘Sudan: Troika Statement, July 2019,’ 18 July, Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/sudan-troika-statement-july-2019> [Accessed 10 October 2019].

- UN News (2019a) ‘Sudan: “Exercise Utmost Restraint” Urges Guterres as Thousands March in Khartoum, Sparking Deadly Clashes’, 8 April, Available at: <https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/04/1036321> [Accessed 13 October 2019]. See also: UN News (2019b) ‘Sudan: Top UN Official Demands Cessation of Violence and Rape against Civilians by Security Forces’, 13 June, Available at: <https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/06/1040471> [Accessed 11 October 2019].

- UN News (2019c) ‘Milestone Agreement Paves the Way for New UN Human Rights Office in Sudan’, 25 September, Available at: <https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/09/1047482> [Accessed 12 October 2019].

- Fund For Peace (2019) ‘Fragile States Index Annual Report 2019’, p. 7, Available at: <https://fundforpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/9511904-fragilestatesindex.pdf> [Accessed 13 October 2019].