Dr Andrea Prah is currently a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Institute for African Studies at East China Normal University based in Shanghai, China. She is also a Research Associate of the Institute for Global Dialogue (associated with the University of South Africa [UNISA]). Her research interests include African Peace and Security studies; Decolonial Political Theory; Africa’s International Relations.

Abstract

This article provides an analysis of less traditional forms of regional security cooperation in Africa through the case study of the Regional Cooperation Initiative for the Elimination of the Lord’s Resistance Army (RCI-LRA) in Central Africa. It explores the progress and shortcomings of this task force. It argues that although its successes were limited by its militarised mandate and approach, the operation has been largely effective in downgrading the threat status of the Lord’s Resistance Army. This example of regional cooperation offers important lessons for other arrangements which deal with similar threats. This type of response represents an emerging trend in security cooperation in Africa and it is clear that task forces of this structure are becoming more frequent in dealing with transnational violence as opposed to more traditional cooperative arrangements organised through the African Union’s African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA).

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the Lord’s Resistance Army has terrorised communities of Northern Uganda and the surrounding region of South Sudan, the Central African Republic (CAR) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In an attempt to eliminate this threat, the African Union-led Regional Cooperation Initiative for the Elimination of the Lord’s Resistance Army (RCI-LRA) was developed. This African Union-authorised task force brought together the states directly affected by the LRA and represented an important example of security cooperation in Africa, with characteristics which are different from traditional arrangements seen with peace support operations. The RCI-LRA is largely heralded as a relative success by the African Union (AU) even though the LRA still exists, albeit at a fraction of the size it once was.

This article seeks to provide a detailed analysis of the RCI-LRA, highlighting its development, challenges and impact on the region. It argues that this task force has been largely effective in downgrading the threat status of the LRA although its successes were limited by its militarised mandate and approach. Nevertheless, there are important lessons to be learnt for other such arrangements. This type of response represents an emerging trend in security cooperation in Africa and it is clear that task forces of this structure are becoming more frequent in dealing with transnational violence, as seen with the development of the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNFTJ) and the G5 Sahel Force. This article draws on data generated from semi-structured interviews conducted with officials at the policy division of the African Union Peace and Security Council as well as key research institutions working on this topic, such as the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) and the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). Secondary source material was obtained from the LRA Crisis Tracker. This dataset was analysed and organised to reflect the quantitative impact of the RCI-LRA on the LRA.

The Lord’s Resistance Army and insecurity in the Central African Region

The development and impact of the LRA under the leadership of Joseph Kony has to be understood within the history and politics of Uganda and the region. However, this is beyond the scope of this paper and is a popular topic that has been widely covered.1 Briefly, the roots of the LRA are linked to historical factors based on an amalgamation of brutal colonial legacies, national struggles for power, and manipulation of uneven regional development. These factors created and sustained specific social cleavages in Uganda. These social divisions resulted in an alienated Acholi community, the community in which the LRA developed.

The Acholi community, located in Northern Uganda, had been economically marginalised since British colonial rule (Branch 2010:26; Doom and Vlassenroot 1999:7). For a long time, political participation was based on this divide and the subsequent ‘ethnic associations’ and socially constructed identities. After independence, these constructions remained, together with the British strategically appointed chiefs who continued to maintain ‘tribal authority’ and in turn reinforced a group political identity (Branch 2010:26). The different constructed ‘tribes’ were encouraged to compete with each other for economic opportunities and political validation (Amone and Muura 2014:249). All these developments worked together to consolidate an Acholi identity. This type of politics inflamed two crises – the crisis for leadership within the Acholi community after independence and the national political crisis – both of which contributed to the development of the LRA. Also, comparisons between the central southern region of Uganda and the north showed that the latter was side-lined from economic and political development (Omara-Otunnu 1995:230). Therefore, the historical militarisation of parts of the Acholi community coupled with the systematic marginalisation of this community through lack of national representation created internal divisions and eventually, politics and mobilisation based on a specific identity.

Along with a lack of national representation of the Acholi community in northern Uganda, the socio-economic grievances of this community increased (Titeca 2010:59–60). The LRA played on these vulnerabilities and gained support for its brutal military campaign against the post-independent government of Uganda. This was exacerbated by the highly militarised politics of Uganda which often pitted Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA) against northern Ugandans (Allen and Vlassenroot 2010:7–8). As suggested by its name, the LRA has been associated with organised religion and specifically, Christian fundamentalism. Tied to the legitimacy of the movement is the fact that their leader, Kony, claims that he is filled with spirits. This belief long sustained the spiritual structure of the LRA which demanded absolute obedience and was crucial to ensuring that the members ‘grow into the LRA’ (Mergelsberg 2005:63). However, an overemphasis on the spiritual aspects of the LRA has often undermined the politics of the LRA. This approach has been most commonly noted in ‘Western media and anthropology’ and has come to frame the group as ‘irrational’, ‘primitive’ and ‘cult-like’ (Titeca 2010:60). Such narratives affect the responses to the LRA. It is therefore more useful to view the spiritual dimensions of the LRA as a means to maintain the unity and organisation of the group by ‘motivating, legitimizing and intimidating the individual fighter’ within the larger socio-economic context of Uganda (Titeca 2010:59).

Over the years, the LRA has increased its numbers through forced recruitment and child abductions. More than 100 000 people have been killed and approximately two million displaced (Fabricius 2016). The latest 2017 statistics published by the Enough Project show that from 1985 there have been over 67 000 abductions, 3000 of whom were children. Such statistics only provide a snapshot as there are many other uncounted victims (The Enough Project 2017; Pham, Vinck and Stover 2008:405). The abductions also extended to southern Sudan, eastern DRC and the eastern CAR. In 2016, there was a serious increase in the number of child abductions (LRA Crisis Tracker 2016:14). The abductees served different roles within the LRA. Young women and girls were sometimes forced to play the role of a ‘wife’ to LRA soldiers. Along with men, they were also forced to act as porters and combatants. The LRA also used abductions as a way to replace defectors or those who had been killed in combat. This created a dependence on abductees, especially from CAR and DRC to fill the lower ranks (LRA Crisis Tracker 2016:14).

In some cases, members were forced to kill their own families and community members, as an initiation into the group (Allen and Vlassenroot 2010:10). Such actions possibly served as binding acts that linked the captives to the LRA, which compelled them to kill or be killed (African Rights Working for Justice 2002:2). The LRA has disrupted every facet of life for communities in the Acholi region. Their systematic violence is not only used for purposes of recruitment, but for looting civilians to stock up on supplies. The LRA Crisis Tracker (2016:6) notes that, ‘In many cases, victims suffer the added indignity of being forced to carry their hard-earned possessions towards remote LRA camps’. In this way, the LRA has contributed to the increasing impoverishment of people in this politically marginalised part of Uganda. The International Crisis Group (2011:9) explained that ‘many communities are too frightened to go to the fields to farm, so use what little self-sufficiency they may have had’. The terror of the group has also led to the massive displacement of people. Many people who face the brunt of LRA attacks in the Acholi region of northern Uganda have tried to escape by moving to neighbouring districts like Gulu, Kitgum, Pader, Lira, Apac, Katakwi, Kaberamaido and Adjumani. Displacement has also been caused by ‘night commuting’ where thousands of young men and children, who may be potential targets for the LRA, commute or walk into the city centres to escape pre-empted night attacks (Lomo and Hovil 2004:39–40).

The construction of the LRA as a transnational threat

The development of the LRA as a transnational threat in the Central African region is attributed to several factors. It is also this characteristic which necessitated the flexible regional response of the RCI-LRA. The first factor which contributed to the transnationality of the LRA was the favourable geographic terrain. For example, the specific type of dense forest terrain allowed the LRA ease of movement in and between these three states (International Crisis Group 2011:2). This is also linked to the porous borders of the states in these parts of the Central African region which contributed to the mobility of the LRA. The transnational element not only refers to the movement of the LRA but also to its economic sustenance through illegal cross-border trade, particularly of ivory (Lomo and Hovil 2004:41). LRA leader Kony has found a ‘safe haven’ in Sudan, in the Kafia Kingi region where South Sudan, Sudan and CAR merge. This area has poor infrastructure and a limited formal economy and is not a particularly important electoral constituency for the three states (LRA Crisis Tracker 2016:15). In this particularly remote area, the LRA conducts its illegal trade in ivory, which is an important source of income. Ivory tusks have been specifically looted from the DRC. Diamonds and gold also form part of their illicit trading. This allows the LRA to resupply without attacking civilians, and this makes it more difficult for the RCI-LRA and the Ugandan forces to track its movements.

These transnational activities of the LRA would not be feasible if there was an effective state presence at the borders. Poor state security apparatuses therefore facilitated the development of the LRA as a transnational threat. This is possibly linked to a lack of resources or capacity within the respective states, but could also be a result of a general lack of state visibility in marginalised sections of the states concerned. The mobilisation of the LRA between Central African borders, coupled with the lack of state capacity to deal with this challenge, has contributed to the establishment of the task forces, which offered a regional solution to deal with the LRA.

Responses to the LRA outside the RCI-LRA

Organised responses to the LRA have not only come from the task forces, but also from separate interventions by civilians in the northern and northeastern parts of Uganda. Before the military offensive offered by the RCI-LRA, community and religious leaders have played important roles in facilitating group responses. From 1994, communities also mobilised in response to the terror of the LRA by forming an informal community security arrangement known as ‘Arrow Boys’, who worked alongside the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF). Initially the Arrow Boys prevented the spread of rebels to the eastern part of Uganda (Lomo and Hovil 2004:54). However, the LRA launched severe counter-attacks on the Arrow Boys, who were regarded as traitors because they were from the same community. The civilian population, suspected of supporting the Arrow Boys, also became targets of brutal maiming and killing. As a result, the Arrow Boys operation was aborted (Branch 2005:24). Other community approaches included those in CAR where communities employed local mediation mechanisms and established ‘Peace Committees’. This platform allowed representatives from different communities to meet and discuss strategies for prevention of further violence. It played an important role in mitigating local hostilities. Furthermore, they assisted LRA abductees, who found themselves stranded hundreds of kilometres from home (LRA Crisis Tracker 2018a). However, communities have also had to deal with LRA defectors attempting to return to a community where they carry the stigma of having been party to LRA violence. In this case, former abductees either do not return to their communities or join new communities in a fractured and tense social environment.

The Ugandan state has tried to intervene through a combination of dialogue and military means to engage the LRA and while there was limited success, it certainly did not bring an end to the war. In the early 1990s, there were fairly successful peace talks led by former minister Betty Bigombe. These talks broke down, however, for several reasons – chief of which was the dwindling political will and weak negotiation strategy of the Ugandan government (Lomo and Hovil 2004:60). Amnesty offers were also made as part of the dialogue and mediation. The Amnesty Act of 2000 offered former rebel Ugandans amnesty for acts committed from 1986 and was a serious attempt to weaken the leadership of the LRA. However, this also met with limited success. The Ugandan government then adopted a more militarised response, starting with Operation Iron Fist. This operation lasted from 2002 to 20052 and attempted to destabilise the military base of the LRA in southern Sudan (African Rights Working for Justice 2002:1). It was largely considered a failure because it did not protect the local communities and made them more vulnerable to attacks from the LRA. Also, if the LRA suspected any community members of involvement with the army, they faced brutal punishment. Moreover, Operation Iron Fist exposed the operational and tactical weaknesses of the Ugandan national army in comparison with a seemingly stronger LRA who was able to manoeuver through the dense forest terrain more easily because they had spent so much time in this type of environment. In 2006, the Ugandan government restarted negotiations with the LRA, with the support of the Sudanese government. An Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities (ACH) was signed, but this peace process eventually failed when the LRA failed to sign a final peace agreement (African Union 2009:13).

This led to the preference for military intervention, which was heavily determined by the Ugandan government’s decision not to negotiate with terrorists, a position encouraged by the United States (US). In fact, the US encouraged Museveni to handle the LRA militarily, as part of the former’s own foreign policy objectives not to encourage negotiation with ‘terrorists’ (Lomo and Hovil 2004:28). A purely military intervention was always problematic in circumstances where it is difficult to distinguish between a captive and an LRA combatant. In addition to this, the government also embarked on domestic ‘counter-insurgency’ operations in northern Uganda. This involved the army arresting and torturing ‘suspected’ LRA collaborators, many of whom were possibly innocent (African Rights Working for Justice 2002:7). This contributed to the erosion of trust between the Acholi community and the Ugandan army and affected the public perception of the army, so that in some cases, the UPDF was seen as an ‘aggressor’. This in turn affected their working relationship and the government lost out on possible valuable sources of intelligence (Lomo and Hovil 2004:44). Such treatment also side-lined the voices of Acholi people who were directly affected by the violence from both sides.

In some cases, the Ugandan government’s response to the conflict was framed in geographic and ethnic terms. This dissatisfied many in northern Uganda who believe that the government was ‘portraying the war in ethnic terms’ (Lomo and Hovil 2004: 36–37). Politicians and Ugandans outside of the northern region have therefore also come to associate Kony with an Acholi, which sustains a socially constructed bias. This type of approach reinforced the political isolationism of the colonial era. Communities in this part of northern Uganda have also faced frequent internal displacement. One of the strategies of the Ugandan government to improve protection was to move people out of their homes in the Acholi region into ‘protected villages’ otherwise known as international displacement camps. However, people are not much safer in these camps and are exposed to inhumane living conditions, violence from the soldiers as well as the LRA who have sometimes looted the camps. This displacement has been considered as a potential source of future conflict (Pham, Vinck and Stover 2008:411).

The Ugandan government continued its militarised response and in 2008 launched Operation Lightning Thunder, also known as the Garamba Offensive. This was a joint operation involving Uganda, DRC and Southern Sudan as well as support from the US. In total, the US committed 100 of its special forces, who acted as military advisors to the region, at a cost of approximately 38 million US dollars. This involved air and ground attacks on LRA camps in the Garamba National Park in the DRC and managed to disperse the LRA from this base between 2009 and 2010. The LRA then retreated into the dense forests of the DRC, southern Sudan and CAR (LRA Crisis Tracker 2016:16). One of the main reasons for the failure of Operation Lightning Thunder was that it lacked troops. Initially Uganda committed 4 500 troops but the number dwindled to 500. In mid-2010, Museveni re-routed troops to other regions within Uganda that were considered more urgent. Ironically, troops were also re-routed into the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). In 2011, the Ugandan Army was also redeployed for the 2011 presidential elections. This lack of commitment does not have dire political consequences for Museveni, as he is under little domestic pressure to finish off the LRA. Furthermore, the LRA has morphed into a regional problem as opposed to a purely domestic issue for the Ugandan state (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:3).

While the LRA moved into other surrounding states quickly, it was not always regarded as a regional problem. Initially, Joseph Kabila (former President of the DRC) did not consider it a national priority and the threat of the LRA was largely downplayed. The same can be said for CAR and Sudan. Instead, these states focused resources on violent challenges within their respective states and border disputes (Lomo and Hovil 2004:5). While this was still considered a ‘Ugandan’ problem, the lack of regional cooperation meant that Uganda could not engage in hot pursuit of the LRA once it had crossed borders, making it impossible to control the attack of a highly mobile LRA. Specific examples of this are linked to the failed Ugandan ground and air assaults while pursuing the LRA in southern Sudan, DRC and CAR during Operation Lightning Thunder. This slowed down the military response and created several problems related to one national army operating in another sovereign territory. This issue was particularly contentious between Uganda and the DRC, who share a tumultuous history. This is based on Uganda’s previous support of rebel soldiers who tried to challenge Kabila’s government (Reliefweb 2012; International Crisis Group 2011:7). This meant that Uganda was initially denied access into the LRA hotspots in the DRC, including the infamous LRA hideout – the Garamba National Park. Poor relations between the Ugandans and local Congolese exacerbated the situation on the ground (Reliefweb 2012). Furthermore, on two separate occasions before the task force was established, the DRC requested that Uganda withdraw its troops from its territory with immediate effect. CAR had also requested the withdrawal of Ugandan troops in 2010 when Ugandan troops were suspected of engaging in illegal diamond trading. The lack of initial cohesion and coordination among these states, who were facing a similar threat, led to a more guided oversight role of the AU in the formation of the task force.

Evaluating the RCI-LRA

The operationalisation of the RCI-LRA

The AU recognised the regional threat of the LRA at a fairly early stage and, in 2009, agreed about its urgency and called on states who had participated in the previous military response to eliminate the LRA (African Union 2009:14). In October 2010, the first AU Regional Ministerial meeting on the LRA was held and brought together affected countries (Uganda, the then Government of South Sudan, CAR and DRC), international partners and the UN. The outcome of the meeting was a call for action to address military, security and humanitarian facets of the crisis. The meeting also requested the appointment of a Special Envoy to provide a coordinating role and canvas for international support (African Union 2011a:2). In July 2011, the Assembly of the AU authorised the Regional Task Force with a joint coordination mechanism and a joint operations centre. Under the chairpersonship of the AU Peace and Security Council (AUPSC), it was endorsed by the UN Security Council (UNSC) in July 2011 (UNSC 2011). The UNSC released a strategy on the LRA in support of the RCI-LRA, which outlined specific points of cooperation for UN actors in this operation, and which was a strategy to improve international cooperation and much needed resource mobilisation.3

There are mixed analyses of the response of the participating states, but according to the International Crisis Group (2011:12), Uganda was not as enthusiastic about the other troop contributing countries and about the intervention of the AU, due to a perceived loss of control over the operation. Other research concluded that Uganda had actually approached the AU to legitimise its military campaign (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:6). Other motivations from participating countries to involve the AU are linked to improving external support and funding. This was confirmed by an interview respondent who asserted that ‘They were really looking for financial support. They really wanted the AU to provide legitimacy and a framework which would give it greater exposure to Western donors’.4 The respondent was involved in organising the first donors conference for the RCI-LRA and added that the initial response from the donor community was very poor because there were other more pressing security challenges on the continent, for example, Somalia.

Eventually, the most prominent donor support came from the US. Between 2009 and 2012, the US State Department pledged 56 million US dollars for equipment, supplies and logistics, and a further 17.7 million US dollars in 2013. In 2012, the European Union (EU) also allocated nine million Euros for humanitarian assistance, and then two million Euros in 2014 (Arieff, Ploch Blanchard and Husted 2015). The US also sent in four helicopters to the RCI-LRA, which assisted with much needed strategic airlifts. US military advisers also assisted in training Congolese troops, focusing specifically on reconnaissance in remote areas like the Garamba National Park, a known LRA hideout (International Crisis Group 2011:14). Many Ugandans did not support the US intervention and equated this increased involvement with more potential civilian casualties (Polly 2012).

While this was an AU authorised (not mandated) mission, the implications of this authorisation are not completely clear. It seems that the AU does not have the responsibility to manage the troops or supply troops as it would have in a peace support operation. Instead, the troops were directly accountable to their respective national commanders. The AU was also not responsible for the remuneration of the troops. The main responsibility of the AU was to provide logistical support to the task force, and possibly to increase political pressure on participating states to cooperate. The authorisation of the AU was therefore merely a ‘legalisation’ of the military intervention. However, according to an official in AUPSC, even this authorisation was not entirely clear to the AUPSC.5 The mandate of this task force was to pursue a purely military solution to eliminate the LRA. It consisted of 5 000 troops, 40% of which were Ugandan. Other troop contributing states included CAR, DRC and South Sudan – states all directly affected by the LRA. Military operations were divided according to the respective states: the Ugandan army operated in northern Uganda and had been allowed into CAR. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo operated in South Sudan and the DRC respectively. Deployment was not boosted and the troop arrangements and number remained the same as they were before the AU authorisation, making it look like a ‘rehatted mission’ (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:6).

The operationalisation of the task force represented an important example of African ownership of problems and Africa’s role as the guarantor of peace and security on the continent Also, there was no immediate support from any non-African states. Mixed responses were reported from the European Union (EU) because of the ad hoc nature of the task force which created questions around legality and accountability (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:5). While the RCI-LRA was a regional response, it existed outside of the formalised regional organisations, like the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). In fact, the EAC and IGAD are mandated by the AU as the key security actors in the region. However, no regional organisation responded to the LRA threat and there was no response from the Eastern African Standby Force nor the Central African Multinational Force. This was possibly because the affected member states were scattered in different regional organisations where it was not an institutional priority for other member states. This makes the RCI-LRA an interesting case of informal regional organisation in response to a crisis.

The progress of the RCI-LRA

The activities of the RCI-LRA have seen casualties both on the civilian and the LRA side, which are largely attributed to the task force’s inability to distinguish between LRA combatants and kidnapped civilians. The successes of this operation were limited by the usual hindrances in AU operations, namely weak intelligence due to national security protocol, poor training, inefficient troop rotation6 and serious equipment shortages. These coordination problems were exacerbated by poor communication where some troops speak French (DRC, CAR) and others English (Uganda, South Sudan). Differences in technology and the types of mobile phones used made it difficult for troops to communicate in remote areas, where the LRA thrived.7 These shortcomings made it difficult for the task team to cover its already challenging and vast jurisdiction. This was exacerbated by the lack of political cohesion in the region (Fabricius 2016:1). The task team also operated in a ‘bad neighbourhood’, where its member states were facing domestic crises, wartime scenarios, and accompanying socio-economic emergencies. The instability in the region also made it easier for the LRA to manoeuver. As mentioned in the previous section, Sudan’s support for the LRA was a major hindrance to any attempts to counter the group. According to an AUPSC official, Khartoum’s involvement also undermined the task force by preventing access for troops within Sudan.8

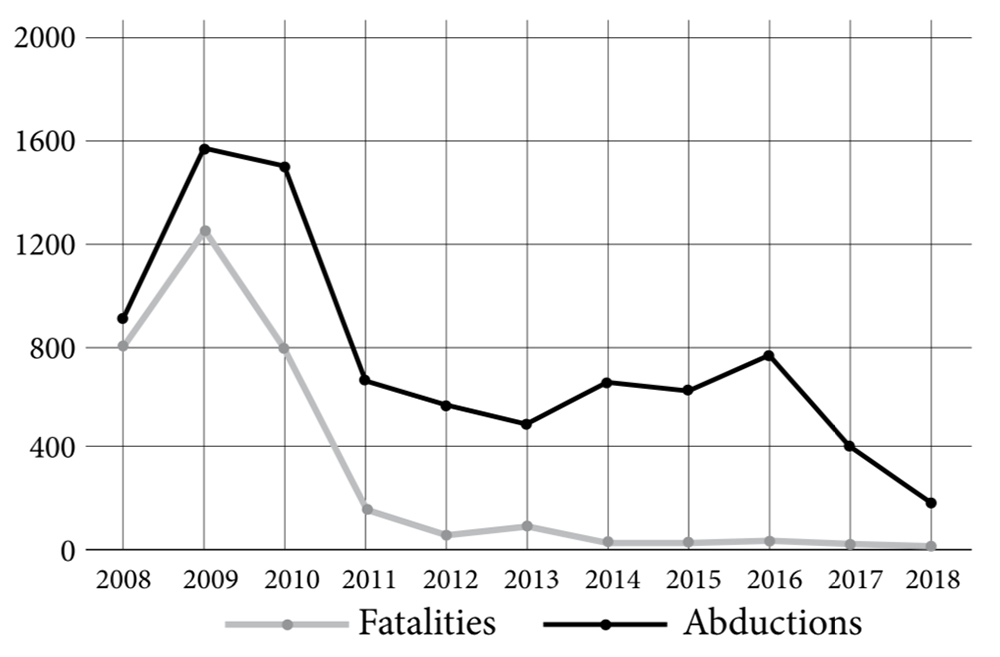

However, while the RCI-LRA was plagued by the abovementioned limitations, it is also clear that its deployment did have an impact on the number of LRA attacks and number of defections (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:8; LRA Crisis Tracker 2016; AU 2018).9 While difficult to conduct due to sovereignty issues, some cross-border patrols acted as a deterrence and allowed civilians more secure freedom of movement. This was specifically seen in CAR, where the UPDF patrolled in ‘secure zones’, which was a five-kilometre radius from the military base (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:11). The graph below (figure 1) indicates the number of civilian fatalities and abductions by the LRA before and during the RCI-LRA operations between 2008 and 2018. From figure 1, it is clear that the LRA activity steadily decreased from the point when the troops were deployed between 2010 and 2012. This decrease was maintained throughout the RCI-LRA operation. A slight increase in abductions between 2013 and 2016 may be explained by ‘opportunistic violence’ which purely focused on the LRA’s ability to survive but also by the internal conflict and instability in South Sudan, CAR and DRC, which represented conditions that left the respective populations vulnerable to attacks from the LRA (LRA Crisis Tracker 2018a).

Figure 1: Civilian fatalities and abductions by the LRA between 2008 and 2018

According to the LRA Crisis Tracker (2018b), the RCI-LRA negatively impacted on the strength and strategies of the LRA. In previous military operations like ‘Iron Fist’ and ‘Lightning Thunder’, the LRA retaliated with more brutal attacks on civilians. However, this pattern of brutal retaliation was not the same with the task teams. While the LRA still maintains a strong core group, its combatant numbers have decreased significantly which has weakened its ability to fight. Several senior leaders have also defected and five senior commanders have been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC). In total, approximately ten high-ranking leaders have defected or been killed (BBC News 2015). Decreased numbers may also be the result of combatants who have been killed as well as those who have defected. The RCI-LRA (in conjunction with US military advisors) also launched a campaign to convince LRA combatants that they may surrender peacefully. The task force would distribute leaflets and ‘come home’ messages over national radio and through helicopter loudspeakers (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:12).

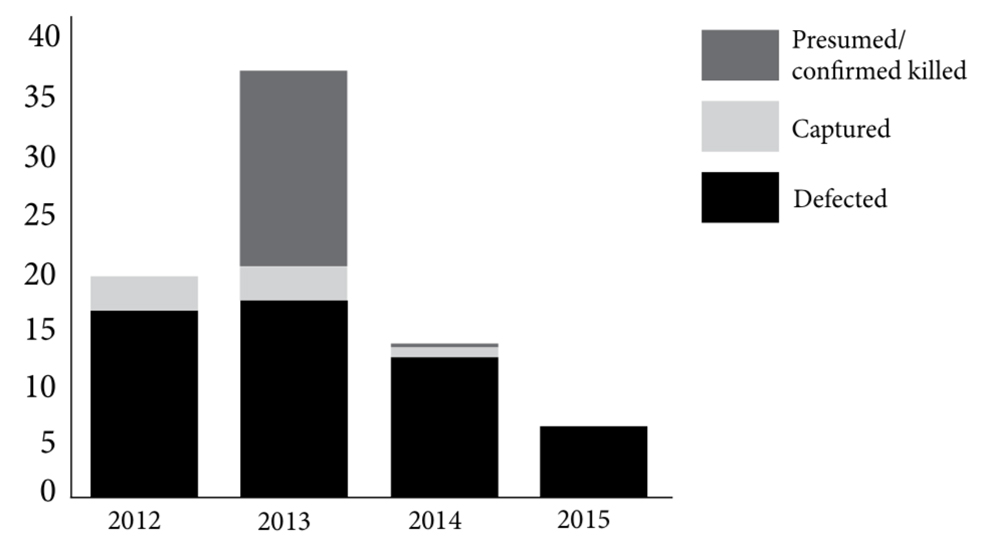

The decreased numbers have led to a fragmented LRA which focuses more on survival than the heinous acts of violence seen from the early 1990s to the 2000s (LRA Crisis Tracker 2016:8). Between 2013 and 2014, there were frequent clashes between the RCI-LRA and LRA forces in Kafia Kingi and eastern CAR and this created more suitable conditions for defection (LRA Crisis Tracker 2018b:9).10 This is depicted in figure 2, which however, only reflects male combatants.

Figure 2: The LRA’s attrition of male Ugandan combatants between 2012 and 2015

Weaknesses of the RCI-LRA

While the significant progress of the RCI-LRA cannot be ignored, there are several weaknesses of the operation that prevented it from being more successful. The central weakness of the RCI-LRA was its purely militarised approach. As discussed in the earlier sections of this paper, the LRA was largely a product of specific socio-economic conditions and weak state governance. While the task force certainly downgraded the strength of the LRA, it could not deal with these underlying structural causes. Another disadvantage of the purely militarised approach, coupled with the structure of the RCI-LRA, was that the AU could not hold the troops accountable for any human rights violations that may have occurred through the military offensive.

There were also provisions for a demilitarisation, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) mandate, which was emphasised in an official communiqué issued by the AU, saying that the RCI-LRA must ‘ensure the mainstreaming of civilian protection in all military and security initiatives aimed at resolving the LRA problem’ (African Union 2011b). However, this was limited by lack of funding and inconsistent implementation, and slowed down by bureaucratic issues. Much of the DDR responsibility lay with the respective participating states, but a lack of coordination within the RCI-LRA and political will from member states made the DDR processes less effective (Lancaster and Cakaj 2013). In addition, even though the RCI-LRA was an effort to coordinate and maintain security cooperation, it did not always work. While the Ugandan army had demarcated patrol zones in CAR, there were cases where cross border operations were impossible because troops had difficulties moving in and between other states. For example, the Ugandan army had difficulty operating in the sovereign territory of the DRC and specifically in the Garamba Park (a known hotspot for the LRA’s ivory trade). Lack of freedom of movement was a severe limitation in an operation where the threat enjoys the ability to move in and between states.

The RCI-LRA suffered a blow when the US withdrew most of its assistance in April 2017. While the US has agreed to keep some troops for training and military exercises in order to prevent a security vacuum, its support has significantly decreased (Allen-Ebrahiman 2017). According to General Waldhauser of AFRICOM, supporting the RCI-LRA was no longer a strategic point of intervention for the US. In a Department of Defence press briefing, he noted that, ‘The bottom line is, this operation, although not achieving the ability to get to Kony himself, has essentially taken that group off the battlefield. And – and (sic) for the last several years, they’ve really been reduced to irrelevance’ (US Department of Defense 2017). Uganda also followed suit by shrinking its military contribution, but has volunteered to host the RCI-LRA headquarters after South Sudan renounced this duty as a possible response to the US withdrawal of support.11 The decreasing of the Ugandan forces was particularly damaging because Uganda was regarded as the ‘lead nation’ in this operation, with the highest number of troop contributions at approximately 2 000 troops (Institute for Security Studies 2017). Uganda still continues to train soldiers in the CAR, however.12 A spokesperson from Uganda’s army said that the army achieved its mandate by neutralising the LRA and that the LRA with ‘less than 100 armed fighters is now weak and ineffective. It no longer poses any significant threat to Uganda’s security and northern Uganda in particular’ (BBC News 2017). This leaves the RCI-LRA with approximately 1 000 troops from CAR, DRC and South Sudan to patrol a vast terrain.

Impact of the RCI-LRA

Based on the data depicted in figures 1 and 2, it is clear that the LRA has been significantly downgraded as a regional threat. The AU noted that ‘the progress made by the RCI-LRA toward the elimination of the LRA, particularly through the operations conducted by the task force, have (sic) significantly degraded the fighting capacity of the LRA’ (African Union 2017). While the LRA still exists and carries out small-scale attacks, the RCI-LRA has made significant progress in achieving its mandate. It may be assumed that the LRA’s effectiveness would have enjoyed more longevity if the task force had not been deployed. The LRA has been reduced to Kony trying to survive on the run and all LRA attacks are just linked to survival. In other words, ‘we do not see the same kind of attacks from the LRA as we did in the 1990’s and early 2000’s’.13 The shift in focus away from the LRA is also due to the competing and larger conflict in CAR as well as pressing humanitarian issues in South Sudan. Such situations have drawn both funding, donor attention and political impetus away from the RCI-LRA. However, the AU still seems committed to keeping the force alive without the major support of the US or Uganda, and has decided to renew the mandate until May 2018 (African Union 2017:2). All interview participants based at the AU agreed that the LRA has largely been defeated and that the RCI-LRA is basically ‘dead in the water’.14 Based on this evaluation of the task force and the relative successes of the RCI-LRA, it is clear that there are important lessons to be learnt for future cooperative arrangements.

Recommendations for future task forces

The RCI-LRA offers important insights for future task forces mandated to eliminate a transnational threat. Below are recommendations that are important at both a policy level and for future analyses of the task forces.

- Clearer oversight role of the AU The RCI-LRA was a mission ‘authorised’ by the AU as opposed to the usual AU ‘mandated’ missions. The implications of this authorisation were not entirely clear for the troops of the task force as they did not report to the AU, which sometimes created problems for the ‘oversight’ role of the AU. Clearer guidelines and policy harmonisation are needed from the AU as to how it relates to the task forces. This has larger implications for the role the AU is able to play in mediating disputes between the participating states of the task forces.

- Increased accountability. This is linked to the first Participating states need to be held accountable for any humanitarian violations by their troops. Many civilians were caught in the crossfire in the hunt for the LRA and such a casualty count cannot be ignored and needs to be addressed.

- Provisions for the task forces within the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). The relative effectiveness of the RCI-LRA coupled with the development of two new task forces illustrates the increasing preference for these arrangements in dealing with transnational These task forces should therefore be included as peace and security mechanisms within the framework of APSA, thereby also complying with AU norms and values.

- Balancing the militarised response with A completely military offensive ignores other structural causes of the conflict. The militarised response only provides limited and temporary success and has serious drawbacks, including provocation of cycles of violence in the affected communities. The socio-economic underpinnings which motivate supporters and combatants of the LRA need to be carefully understood and addressed in order to avoid a resurgence of violence.

- Increased focus on An important point of intervention to avoid a completely militarised approach is to support and fund DDR programs which ensure that former combatants are reintegrated into society and the economy. Psychological rehabilitation is key for former combatants who have been consistently exposed to violence and other forms of abuse. This is crucial in cases where combatants were kidnapped as children and socialised into particularly violent patterns of behaviour.

- Involvement of community, traditional and religious Community groups, and traditional and religious leaders have an integral role to play in the conflict resolution and the reintegration of former combatants. Indigenous conflict resolution should be prioritised as a key point of intervention.

Conclusion

It is clear that the RCI-LRA has made significant progress in downgrading the LRA to a minimal threat status. The LRA is still in existence but is a shadow of its former self, a feat which the existing analyses and the fieldwork of this research have attributed to the RCI-LRA. The implications of this effort illustrate the potential for security cooperation in Africa under specific conditions. Based on the evaluation of the task force, the most important conditions are: proximity to the threat, and impact of the threat. These conditions created commonalities among the member states which facilitated cooperation, that would have been unlikely in any other scenario. The central weakness of this approach was the purely militarised strategy which did not address the larger structural social and economic issues of northern Uganda. These were the very issues which Kony capitalised on, to mobilise the LRA combatants in the first place. The LRA still remains a downgraded security threat, but it is no longer a priority for both the AU and the states of the task force. As noted, Kony and a small group are still on the run, and remain an uncertain future threat for the region.

Endnotes

- See Karugire (1980:100); Speke (1863); Amone and Muura (2014); Ginyera-Pinycwa (1992); Omara-Otunnu (1995); Dunn, 2010:9; Fearon and Laitin (2003); and Von Acker (2004:338–339).

- In 2005, a Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed, as a result of negotiations between the LRA and Kampala. However, there was a problem with commitment from both sides. There was a complete breakdown in negotiations in 2008 with Kony refusing to sign the draft agreement (International Crisis Group 2011:1).

- The UNSC strategy focussed on five objectives: ‘Implementation of the RCI-LRA; enhancement of efforts to promote the protection of civilians; expansion of current disarmament, demobilisation, repatriation, resettlement and reintegration activities to cover all LRA-affected areas; promotion of a coordinated humanitarian and child protection response in all LRA-affected areas; and provision of support to LRA-affected governments in the fields of peacebuilding, human rights, rule of law and development, so as to enable them to establish state authority throughout their territory’ (UN Department of Political Affairs 2012).

- Non-attributable comment by UN political officer, 16 July 2018, Tripoli.

- Non-attributable comment by AU official, 9 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

- An important example of this was seen when Uganda moved troops out of CAR and replaced them with inexperienced and poorly trained troops. As a result, many troops were garrisoned for training which reduced the actual number of troops on patrol (Shepherd, Davis and Jowell 2015:9).

- Non-attributable comment made by AU official, 7 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

- Non-attributable comment made by a second AU official, 7 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

- Non-attributable comments made by AU officials, 7 and 9 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

- In many cases, those who escape the LRA are hundreds of kilometres away from home. Poor infrastructure in the remote rural areas where the LRA operate make it difficult for returnees to access government services. According to the 2017 Annual Brief of the LRA Crisis Tracker (2018a:9), approximately 14 returnees (including children) are stranded.

- Non-attributable comment by AU official, 7 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

- Non-attributable comment by AU official, 7 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

- Non-attributable comment by ISS researcher, 26 July 2018, Pretoria.

- Non-attributable comment by UN official, 16 July 2018, Tripoli; Non-attributable comment by ISS Researchers, 26 July 2018, Pretoria, and 4 August, Addis Ababa; Non-attributable comment by AU officials, 9 August 2018, Addis Ababa.

Sources

- African Rights Working for Justice 2002. Operation Iron Fist: What price for peace in Northern Uganda? Pambazuka News. Available from: <https://www.pambazuka.org/human-security/operation-iron-fist> [Accessed 21 June 2018].

- African Union 2009. Report of the Chairperson of the Commission – Special Session of the Assembly of the Union on the Consideration and Resolution of Conflicts in Africa. Tripoli, 30–31 August 2009. Available from: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/report-ch-tripoli-special-session-final-eng-.pdf> [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- African Union 2011a. Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Operationalization of the AU-led Regional Cooperation Initiative Against the Lord’s Resistance Army. Peace and Security Council 299th Meeting. Addis Ababa, 22 November 2011. Available from: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/pressreleases/24637-pr-299th_psc_report_eng.pdf> [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- African Union 2011b. Communiqué of the African Union Peace and Security Council PSC/PR/CCXCVIX. 22 November 2011. Addis Ababa.

- African Union 2017. African Union Peace and Security Council 685th meeting Communiqué PSC/PR/COMM.(DCLXXXV). Addis Ababa, 12 May 2017.

- Allen, Tim and Koen Vlassenroot 2010. The Lord’s Resistance Army: Myth and reality. London, Zed Books.

- Allen-Ebrahiman, Bethany 2017. US will keep fighting Lord’s Resistance Army after all. Foreign Policy, 21 April 2017. Available from: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/21/u-s-will-keep-fighting-lords-resistance-army-after-all/> [Accessed 28 August 2018].

- Amone, Charles and Okullu Muura 2014. British colonialism and the creation of Acholi ethnic identity in Uganda, 1894 to 1962. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 42 (2), pp. 239–257.

- Arieff, A., L. Ploch Blanchard and T.F. Husted 2015. The Lord’s Resistance Army: The U.S. Response. Congressional Research Service, 28 September 2015. Available from: <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R42094.pdf> [Accessed 27 August 2018].

- BBC News 2015. LRA rebel Dominic Ongwen surrenders to US forces in CAR. BBC News, 7 January 2015. Available from: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30705649> [Accessed 27 August 2018].

- BBC News 2017. Uganda ends hunt for LRA leader Joseph Kony. BBC News, 19 April 2017. Available from: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-39643914> [Accessed 28 August 2018].

- Branch, Adam 2005. Neither peace nor justice: Political violence and the peasantry in northern Uganda, 1986 1998. Africa Studies Quarterly, 8 (2), pp. 1–31.

- Branch, Adam 2010. Exploring the roots of LRA violence: Political crisis and ethnic politics in Acholiland. In: Allen and Vlassenroot eds. pp. 25–44.

- Doom, Ruddy and Koen Vlassenroot 1999. Kony Message: A new Koine? The Lord’s Resistance Army in Northern Uganda. African Affairs, 98 (390), pp. 5–36.

- Dunn, Kevin 2010. The Lord’s Resistance Army and African International Relations. African Security, 3 (1), pp. 46–63.

- Fabricius, Peter 2016. The LRA are rising again. ISS Today, 2 July 2016. Available from: <https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-lra-rising-again> [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- Fearon, James and David Laitin 2003. Ethnicity, insurgency and civil war. American Political Science Review, 97 (1), pp. 75–90.

- Ginyera-Pinycwa, Anthony G.G. 1992. Northern Uganda in National Politics. Kampala, Fountain.

- Institute for Security Studies 2017. Why is the AU going it alone in fighting the LRA? Peace and Security Council Report. Available from: <https://issafrica.org/pscreport/on-the-agenda/why-is-the-au-going-it-alone-in-fighting-the-lra> [Accessed 28 August 2018].

- International Crisis Group 2011. The LRA: End Game? Africa Report No 182. Available from <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/lord-s-resistance-army-end-game> [Accessed 25 June 2018].

- Karugire, Samwiri Rubaraza 1980. A Political History of Uganda. Nairobi, Heinemann Educational.

- Lancaster, Phil and Ledio Cakaj 2013. Loosening Kony’s grip: Effective defection strategies for today’s LRA. The Resolve LRA Crisis Initiative Available from: <http://www.theresolve.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Loosening-Konys-Grip-July-2013-FINAL.pdf> [Accessed 27 August 2018].

- Lomo, Zachary and Lucy Hovil 2004. Behind the violence: The war in Northern Uganda. Institute for Security Studies. Monograph 99. Available from <https://issafrica.org/research/monographs/monograph-99-behind-the-violence.-the-war-in-northern-uganda-zachary-lomo-and-lucy-hovil> [Accessed 27 June 2018].

- LRA Crisis Tracker 2016. The State of the LRA in 2016. The Resolve LRA Crisis Initiative. Available from: <https://reports.lracrisistracker.com/pdf/2016-The-State-of-the-LRA.pdf > [Accessed 22 June 2018].

- LRA Crisis Tracker 2018a. 2017 Annual Brief. The Resolve LRA Crisis Initiative. Available from: <https://invisiblechildren.com/blog/2018/03/21/lra-crisis-tracker-2017-annual-brief-released/> [Accessed 23 June 2018].

- LRA Crisis Tracker 2018b. LRA Crisis Tracker Dashboard. Available from: <https://www.lracrisistracker.com> [Accessed 25 August 2018].

- Mergelsberg, Ben 2005. Crossing Boundaries: Experiences of returning ‘child soldiers’. Draft report, December 2005. Cited in Titeca 2010.

- Non-attributable comment made by AU official, 7 August 2018, Addis Ababa. Non-attributable comment made by AU official, 9 August 2018, Addis Ababa. Non-attributable comment by ISS researcher, 26 July 2018, Pretoria.

- Non-attributable comment by ISS researcher, 4 August, Addis Ababa.

- Non-attributable comment made by second AU official, 9 August 2018, Addis Ababa. Non-attributable comment made by UN political officer, 16 July 2018, Tripoli.

- Omara-Otunnu, Amii 1995. The dynamics of conflict in Uganda. In: Furley, O.W. ed. Conflict in Africa. London/New York, I.B. Tauris. pp. 223–236.

- Pham, Phuong, Patrick Vinck and Eric Stover 2008. The LRA and forced conscription in Northern Uganda. Human Rights Quarterly, 30 (2), pp. 404–411.

- Polly, Curtis 2012. Hunt for Joseph Kony will kill more innocent people, charities warn. The Guardian, 19 April 2012. [J/OL] Available from: <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/19/hunt-joseph-kony-kill-innocents> [Accessed 27 August 2018].

- Reliefweb 2012. African Union welcomes progress made towards eliminating the Lord’s Resistance Army. Reliefweb, 12 September 2012. Available from: <http://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/african-union-welcomes-progress-made-towards-eliminating-lord%E2%80%99s-resistance-army> [Accessed 27 August 2018].

- Shepherd, B., L. Davis and M. Jowell 2015. In new light: protection of civilians, the Lord’s Resistance Army and the African Union Regional Task Force. Conciliation Resources. Available from: <http://www.c-r.org/downloads/InNewLight_AURTF%20and%20POC_May2015.pdf> [Accessed 27 June 2018].

- Speke, John 1863. The journey of the discovery of the source of the Nile. London, Unwin.

- Titeca, Kristof 2010. The Spiritual Order of the LRA. In: Allen and Vlassenroot eds. pp. 59–74.

- The Enough Project 2017. The Enough Project. Available from: <http://enoughproject.org/conflict/org> [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- UN Department of Political Affairs 2012. UN and partners build momentum in the fight against the LRA. UN Department of Political Affairs E-News, July 2012. Available from: <http://www.un.org/wcm/content/site/undpa/lang/en/main/enewsletter/news0612_lra> [Accessed 27 August 2018].

- United Nations 2011. Security Council Press Statement on Lord’s Resistance Army SC/10335, 21 July 2011. Available from: <https://www.un.org/press/en/2011/sc10335.doc.htm> [Accessed 24 August 2018].

- U.S. Department of Defense 2017. Department of Defense Press Briefing on U.S. African Command by General Thomas D. Waldhauser, commander. U.S. Africa Command transcript, 24 March 2017. Available from: <https://dod.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/1130131/department-of-defense-press-briefing-on-us-africa-command-by-general-thomas-d-w/> [Accessed 28 August 2018].

- Van Acker, Frank 2004. Uganda and the Lord’s Resistance Army: The new order no one ordered. African Affairs, 103 (412), pp. 335–357.