Introduction

Disengagement, rehabilitation and reintegration for members of violent extremist groups during ongoing conflict is a tricky matter. Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) programmes are normally implemented after a peace agreement is in place. However, this does not apply to south central Somalia, as well as other conflict-ridden areas around the world today. Providing adequate security for those wanting to leave violent extremist groups is arguably a key element for success for programmes operating in such contexts. This article looks at some of the security challenges the Defector Rehabilitation Programme (DRP) for al-Shabaab members has encountered in south central Somalia. The lessons learnt presented in this article were mainly gathered through discussions and presentations made at a training held in Nairobi in November 2017 by the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) for programme staff in the DRP. Interviews and conversations were also carried out with staff members and partners involved in different stages of the programme, and practitioners and stakeholders working to prevent or counter violent extremism in Somalia, during field trips to south central Somalia between 2013 and 2017.

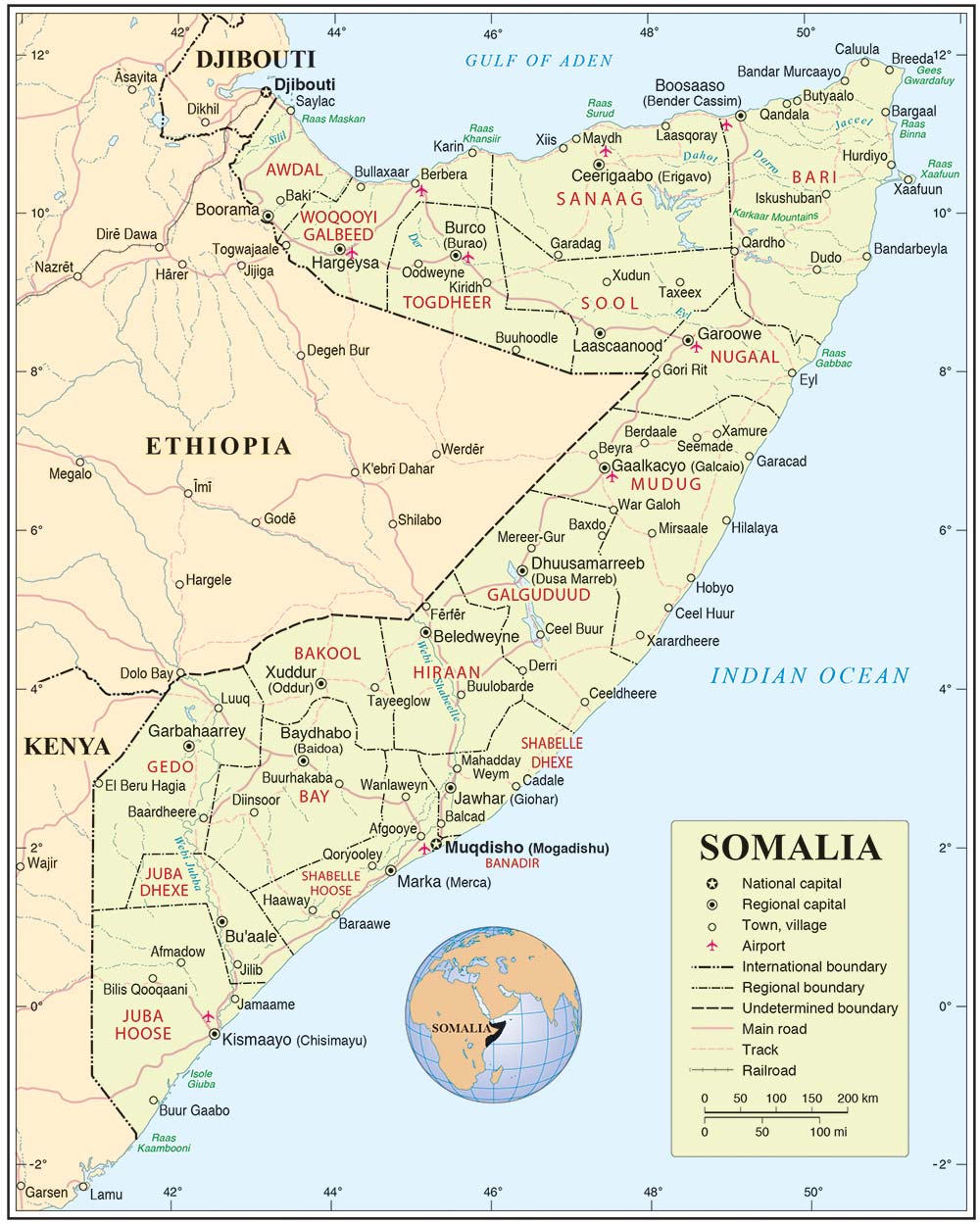

Context

In the Global Terrorism Index (2018), Somalia was ranked sixth on the list of countries most impacted by terrorism in 2017.1 Al-Shabaab, was behind the deadliest terrorist attack in 2017 worldwide, when a suicide bomber detonated an explosives-laden truck, killing 587 people, in Mogadishu on 14 October.2 Al-Shabaab also carries out attacks in neighbouring countries, such as the mass shooting at Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi in 2013, the Garissa University College attack in 2015 and the attack on a corporate campus in Nairobi in January 2019. Although al-Shabaab has had several military setbacks since 2012,3 these attacks – as well as frequent smaller attacks in and outside of Somalia – demonstrate that the group still poses a significant threat to security and stability in the region.

Al-Shabaab is affiliated with and has pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda, and is listed as a terrorist organisation by many countries. Initially, al-Shabaab mainly had a national focus, aiming to take over power in Somalia. However, in recent years, the organisation has changed its profile stating that the Somali fight is also a part of a “global jihad”. In addition to recruitment locally, the organisation has attracted members from western countries as well as other parts of eastern Africa. As the name al-Shabaab (“the youth”) indicates, young people predominate in the group.

The total size of al-Shabaab is unclear, but it has been estimated that the organisation consists of between 7 000 and 9 000 people.4 In 2014, Botha and Abdile published their study, “Radicalization and al-Shabaab Recruitment in Somalia”,5 based on interviews with close to 100 former al-Shabaab members. Of these interviewees, 91% had joined before turning 30, and 40% joined between the ages of 15 and 19.

The reasons why some young people choose to join al-Shabaab varies. For some, it is seen as a career opportunity and a way to support themselves and their families. Other motivations are grievances and revenge, religious convictions, increased status and power, seeking protection or adventure, or a combination of various factors.6 Some are recruited by force. As members of al-Shabaab, many experience disillusionment with the group, the leadership, the cause or the methods employed.7 Others find the salary they receive in al-Shabaab inadequate or have family obligations that make them want to return to civilian life.8 Some seized the opportunity and disengaged after President Mohamed Abdullahi “Farmajo” Mohamed publicly announced, in April 2017, a 60-day amnesty for al-Shabaab fighters willing to give themselves up.9 The question then arises: how to assist those who want out?

The Defector Rehabilitation Programme

The DRP in south central Somalia operates under the auspices of the Federal Republic of Somalia and the Ministry of Internal Security. The programme has gone through several changes since it was launched in 2012, and today it has nine rehabilitation centres in various locations in south central Somalia, supported or run by international organisations in cooperation with the Ministry.10 As set out in the programme’s policies and procedures,11 the DRP consists of five phases: outreach, reception, screening, rehabilitation and reintegration. Outreach activities seek to spread information to individuals and communities about the programme, to encourage people to leave al-Shabaab. In the reception phase, the people entering the programme are received by national or international forces. The National Intelligence Security Agency (NISA) is responsible for the screening phase, where these individuals are assessed as either low or high risk. The high-risk cohort is taken to safe houses, or sentenced and imprisoned. Individuals in the low-risk group – which is the main focus in this article – are transferred to rehabilitation centres; young persons under 18 years are placed in separate centres for minors. In the rehabilitation centres, the participants are offered basic education and different types of vocational and skills training. During the reintegration phase, programme participants move out of the centres for relocation to local communities. During the start-up of the programme, emphasis was mainly on the rehabilitation process. However, in recent years, efforts have been made to develop and improve the other four phases of the programme; such as implementing new screening mechanisms, upscaling the outreach activities and further developing the reintegration framework.12

To Stay or Leave? Security Considerations before Deciding to Disengage

Leaving a violent extremist organisation involves taking risks. People thinking of disengaging from such groups must give careful consideration to whether it feels safe to do so. Safety for one’s own person – in addition to family members, dependants and others – tops the “basic needs list” in an exit process. Al-Shabaab employs various means of discouraging its members from leaving, including threats and punishment. It has developed efficient mechanisms for keeping the organisation together – for example, by establishing the Amniyat, the al-Shabaab intelligence division and secret police, who are feared within and outside the organisation.13 Intelligence gathering and infiltration are some of al-Shabaab’s greatest strengths. In several cases, people trying to leave the organisation have been killed, or the Amniyat has targeted their family members.14 In addition to the threat posed by the group itself, al-Shabaab members fear potential persecution by national security forces. A further threat is retaliation by local communities, victimised by the actions and atrocities of al-Shabaab. Combined, these security challenges make it difficult for members of al-Shabaab to exit the organisation.

Being able to guarantee robust security measures is crucial to have an impact on the level of disengagement.

For the DRP to provide an attractive alternative to membership in al-Shabaab, people considering exiting need to know that their security will be ensured throughout all phases of the programme. Protection from threats and risks, access to safe transport to rehabilitation centres, and safekeeping of sensitive information are central in the programme’s three first phases (outreach, reception and screening). It is also vital to ensure that programme participants are treated humanely and with respect, according to national and international human rights law.

Who to Trust? Living in a DRP Rehabilitation Centre

The fourth phase of the programme for the low-risk group is the rehabilitation process, conducted in the rehabilitation centres. The average time programme participants live in the centres may vary between the centres, and depends on the individual participant’s needs and circumstances.15 As the programme is intended to weaken al-Shabaab, the rehabilitation centres are potential targets, at risk of being attacked. A continuous challenge is therefore to ensure that the premises are properly secured and the people there protected. A further challenge is infiltration by al-Shabaab. There have been incidents where active al-Shabaab fighters entered the programme, pretending to want to disengage. In some cases, it is challenging to determine who is a potential infiltrator and who is genuinely seeking exit from the group.16 Safekeeping of information is therefore important to prevent sensitive information about the centres, and the staff and participants staying there, from falling into the wrong hands. However, providing a safe space, training, education and presenting the participants with alternative worldviews may also prove to have a positive impact, even on infiltrators. In one case, an al-Shabaab member infiltrated a centre; then, after having spent some time there, decided to continue in the programme and leave al-Shabaab.

There are also security risks involved in bringing together, inside the same facilities, people who have been involved in a violent organisation. People who have been trained in and have carried out violence are vulnerable to post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and aggressive and violent behaviour. Some are also victims of violence themselves. High priority must be given to psychosocial treatment to decrease levels of unrest and violence within the centres. Moreover, the command and control structure of al-Shabaab subgroups was, in some cases, brought into the centres. Detecting this early and having sufficient trained staff available to recognise and dismantle such group dynamics is essential.

During the time participants stay in the rehabilitation centres, they communicate with friends and family on the outside, including people who are still active members of al-Shabaab. If former members feel safe and have positive experiences while in the centres, this message may be conveyed further, thereby increasing the chances of motivating others to join the programme.

Now What? The Reintegration Phase

In the final stage of the programme, the reintegration phase, security is also a major challenge. Due to al-Shabaab’s modus operandi, it is hard to know whom to trust in a community. Al-Shabaab has “sleeper cells”, where members are embedded in local communities and their role in al-Shabaab is kept hidden until the cell is activated. In addition, there are areas that are still controlled by al-Shabaab where the organisation has significant support from the local population. All these factors make the thorough assessment of possible locations for relocating programme participants when they move out of the rehabilitation centres a challenging but highly important task. Careful consideration must be given to whether participants will be secure living with family, relatives or others in their networks. Some may have family members or friends who are still active members or supporters of al-Shabaab. In some cases, the best solution is to relocate individuals to a different area than their community of origin.

Some local communities are hesitant to receive former members of al-Shabaab. As a result, individuals may be stigmatised or isolated in the reintegration process if their background should become known. Some of those who decide to leave al-Shabaab do so quietly, without entering a programme, simply trying to settle into a new environment anonymously. To be able to provide an alternative to such “self-reintegration”, the programme needs to have a specific, detailed individual plan for each participant, to mitigate security risks in the reintegration phase. The safety of those who are relocated to a local community may, in some cases, hinge on the willingness of clan leaders, elders, religious leaders and other central figures to provide protection and support. Respected leaders in the communities are also in a position to initiate and employ traditional methods of conflict resolution and restorative justice processes to prevent harmful or unwanted reactions from local communities. Establishing, improving and maintaining cooperation with such local resource people should therefore be a key component in the further development of the reintegration phase. Close involvement of local leaders, as well as family members, mentors and, in some cases, local security forces, may prevent individuals from returning to al-Shabaab or becoming involved in other violent or criminal activities and milieus.

Security for Programme Staff and Resource People

Another central issue is the security of programme employees and key people in the communities and local institutions involved in the various phases of the DRP. For example, local staff at the DRP rehabilitation centres are potential targets for al-Shabaab, and risk being attacked, killed or pressured for information. This also applies to their families. For this reason, many staff members try to keep their involvement in the programme hidden. As Botha and Abdile17 point out, providing secure housing and transport to and from work for local staff working at the DRP centres could help to make them less vulnerable. Protection measures for family members of staff should also be taken into consideration. Moreover, to prevent infiltration through employees, thorough background checks must be conducted when hiring staff, accompanied by regular follow-up of employees. Also, resource people and organisations involved in the four other phases of the programme should be subjected to a thorough assessment of potential risks, and necessary protection measures should be applied.

Conclusion

Lessons learned from the DRP in south central Somalia shows that disengaging, rehabilitating and reintegrating al-Shabaab members in the midst of the still-ongoing conflict is not an easy task. The context is complex, with high levels of insecurity, and the modus operandi of al-Shabaab makes it difficult to protect disengaging members from risks and threats throughout the various phases of the programme. Attacks from al-Shabaab, infiltration and reprisals from local communities are some of the challenges encountered. Programme staff and partners, especially at the local level, are equally at risk and in need of protection. Constant consideration and an assessment of security is required for the programme to achieve its goals. If current members of al-Shabaab do not feel it is safe to enter the programme, they may either opt to remain in the extremist group or try to exit on their own. The various security risks demonstrate the challenging, but necessary, task of establishing robust measures to mitigate risks in the further development and implementation of the DRP, if the programme is to succeed in weakening al-Shabaab. These lessons learnt from the DRP are applicable not only to south central Somalia, but have wider relevance for similar programmes and contexts across Africa, as well as globally.

Endnotes

- The Institute for Economics and Peace (2018) ‘Global Terrorism Index 2018. Measuring the Impact of Terrorism’, IEP report, Available at: <http://globalterrorismindex.org/>

- Ibid., pp. 4 and 10.

- Hansen, Stig Jarle (2013) Al-Shabaab in Somalia. The History and Ideology of a Militant Islamist Group 2005–2012. London: Hurst.

- BBC News (2017) ‘Who are Somalia’s al-Shabab?’, BBC News World – Africa, 22 December, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15336689>

- Botha, Anneli and Abdile, Madhile (2014) ‘Radicalization and Al-Shabaab Recruitment in Somalia’, ISS Paper 266, Available at: <https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/Paper266.pdf>

- Khalil, James, Brown, Rory, Chant, Chris, Olowo, Peter and Wood, Nick (2019) ‘Deradicalisation and Disengagement in Somalia. Evidence from a Rehabilitation Programme for Former Members of Al-Shabaab’, RUSI Whitehall Report 4–19, Available at: <https://rusi.org/publication/whitehall-reports/deradicalisation-and-disengagement-somalia-evidence-rehabilitation>; Hansen, Stig Jarle (2013) op. cit.; and Botha, Anneli and Abdile, Madhile (2014) op. cit.

- Botha, Anneli (2017) ‘Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Former Al-Shabaab Fighters in Somalia’, RIMA Occasional Papers 5, No. 25, Available at: <https://muslimsinafrica.wordpress.com/2017/12/04/rehabilitation-and-reintegration-of-former-al-shabaab-fighters-in-somalia-dr-anneli-botha/>

- Khalil, James et al (2019) op. cit.

- BBC News (2017) ‘Al-Shabab Fighters Offered Amnesty as New Somali President Declares War’, BBC News World – Africa, 6 April, Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-39513909>; and Khalil, James et al (2019) op. cit.

- Tervahartiala, Anna (2017) ‘From Al-Shabaab Back Home’, Elm Magazine, 21 December, Available at: <http://www.elmmagazine.eu/articles/from-al-shabaab-back-home/>

- Federal Republic of Somalia (2017) National Programme Policies and Procedures. Ministry of Internal Security, Defectors Rehabilitation Programme.

- Khalil, James et al (2019) op. cit.

- Hansen, Stig Jarle (2013) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- In the National Programme Policies and Procedures document (2017), it is estimated that the time the participants stay in the centres ranges from six to 24 months. In one of the centres in Mogadishu, residency is ideally regarded to last around six months up to a maximum of one year [Khalil, James et al (2019) op. cit., p. 19].

- According to the RUSI report [Khalil, James et al (2019) op. cit., p. 21], screening procedures were improved in recent years through the development of a standardised screening tool to more adequately determine risk levels and eligibility criteria for rehabilitation in relation to at least one of the centres.

- Botha, Anneli and Abdile, Madhile (2014) op. cit.