Introduction

This article presents the results of a study conducted in the Bidibidi Refugee Settlement in the Yumbe District of Uganda between June and August 2018. It examines the conflict trends between refugees and host communities. The aim was to understand the drivers and dynamics of conflicts in the settlement.

This article highlights the key findings of the study and some suggestions for conflict transformation for better relationships. The data collection process took 20 days. The methodology used for this research was based on qualitative study design. Qualitative data collection was done through focus group discussions using interview guides, direct observation, and structured and semi-structured interviews with different community-level committees, such as refugee welfare committees (RWCs) and the host population. Non-structured interviews and informal meetings were also held to collect complementary information, especially with the various stakeholders, such as local government officials, the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other implementing partners. Direct observation was used to confirm conflict dynamics reported during interviews, for validity and reliability. This study was inspired by the conflict transformation theory of Lederach. According to Lederach,1 conflict is normal and dynamic within human relationships and can be seen as a catalyst for growth.

Context

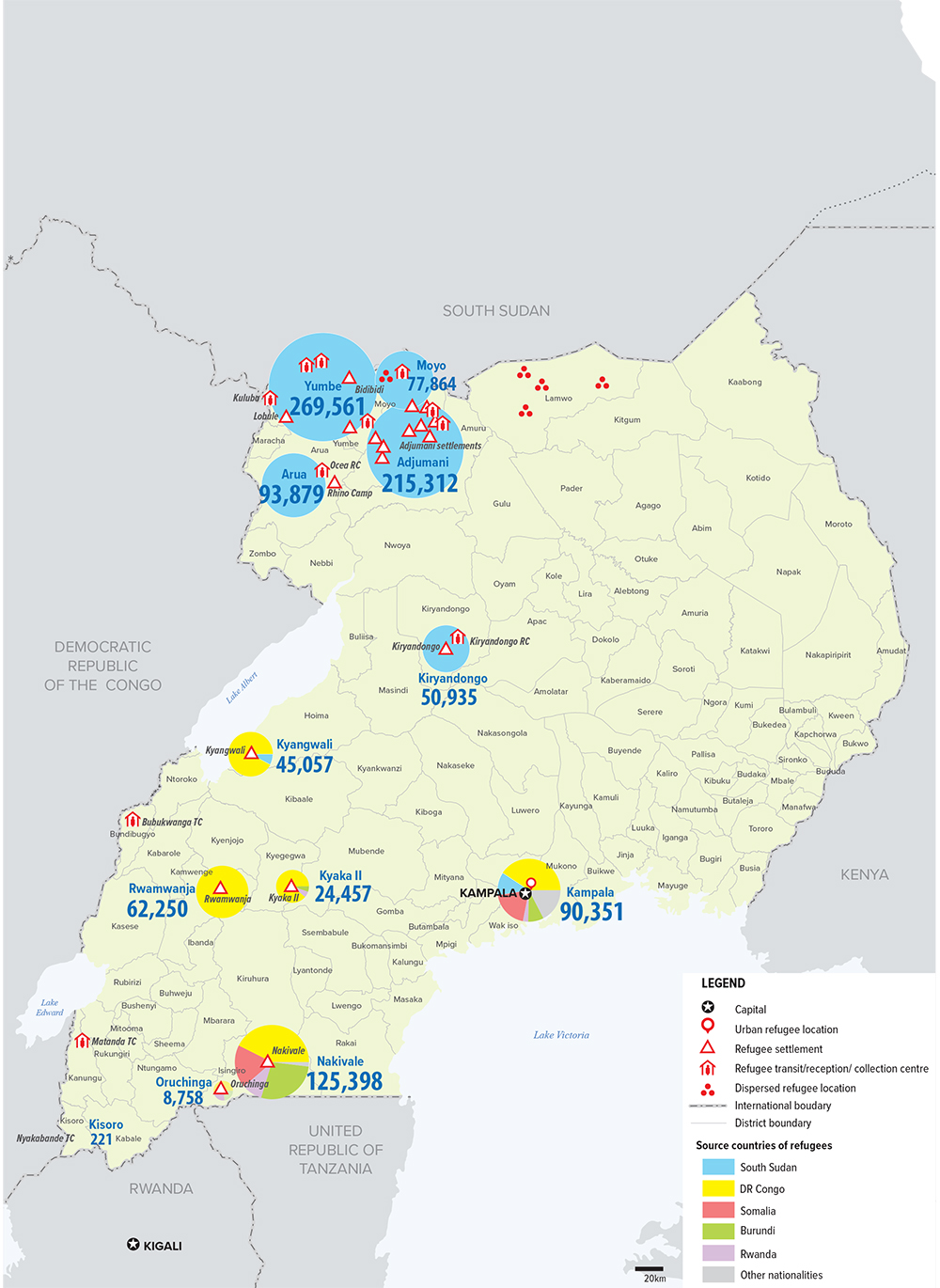

Violent conflict in South Sudan from 2013 to 2016 forced over 977 746 refugees to flee to Uganda, according to statics from the UNHCR.2 Some 86% of those who fled were women and children, with children making up more than 60% of all refugees. The majority of these refugees were settled in the West Nile region of Northern Uganda.

Uganda is a landlocked country located in East Africa and the Great Lakes Region. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. It covers an area of 241 038 square kilometres. The population is estimated to be 34.6 million inhabitants,3 with farming as the main economic activity. The country is also home to 56 tribes, all speaking different languages and with different cultural practices. Uganda’s refugee policy is one of the world’s most progressive, promoting refugee integration rather than confinement, and directing aid resources to the host as well as the refugee population.

Refugees and Uganda

Uganda ratified the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1987.5 According to Muluba,6 the presence of refugees in Uganda dates back to the 1940s with the hosting of Polish refugees at Nyabyeya and Koja in Masindi Mukono. However, in 1955, Uganda became involved in a serious situation when some 78 000 refugees from southern DRC, Sudan and Kenya entered its borders. In 2017, World Vision Uganda estimated that 1 064 043 refugees and asylum-seekers lived in Uganda.7 World Vision Uganda also estimated that 68% of this number – equivalent to 723 550 refugees – were from South Sudan alone. Refugees from Rwanda and Burundi have also fled to Uganda. By late 2017, Uganda had the highest refugee/asylum-seeker population in Africa.

The West Nile region is located in the north-west corner of Uganda. It borders South Sudan to the north and the DRC to the east. The region’s ethnic groups include the Lugbara, Alur, Kakwa and Madi. Political instability in the DRC and South Sudan has a direct impact on the region. The multi-ethnic profile of the area creates conflict in terms of cultural difference, intermarriages and migration to urban satellite towns. For over 20 years, West Nile was cut off from the rest of Uganda, due to the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) insurgency in Northern Uganda and the Uganda National Rescue Front II (UNRF II), which ended with the signing of a peace treaty between UNRF II and the Government of Uganda in 2002. The conflict mainly affected the districts of Yumbe, Koboko Arua and Moyo.8 Until late 2000, West Nile was home to thousands of South Sudanese refugees, who returned after the signing of the comprehensive peace agreement between Sudan and South Sudan in 2005.

South Sudan become independent in 2011. In 2013, the internal power struggle within the ruling party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), resulted in clashes in the capital city, Juba. These clashes quickly turned into targeted killings against Nuer, the ethnic group of South Sudan’s vice president, Riek Machar, who fled into hiding and later became the leader of a rebellion against President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka. Civilians were regularly and deliberately targeted in the conflict, leading to large-scale displacements.

Unfortunately, violence continued in South Sudan. According to the Inter-Agency Regional Analysts Network,9 350 000 refugees from South Sudan crossed to the West Nile region between January and October 2017. Because of the high influx, nine new settlements were opened, with Bidibidi as the largest,10 sheltering over 285 000 South Sudanese refugees, predominantly from the Equatoria region. Most of the refugees were women. In 2017, Bidibidi was described as the largest refugee settlement in the world.11

Conflict Dynamics in the Bidibidi Refugee Settlement

The Bidibidi settlement covers an area of 250 square kilometres. It is composed primarily of underutilised “hunting grounds”, considered by the host communities as unsuitable for agriculture. The area consists of low, rolling hills and mostly rocky soil. Bidibidi is divided into five zones, and each of these zones is divided into clusters, which are further divided into individual villages surrounded by host community settlements. Refugee leadership structures parallel Uganda’s own local governance model, which is composed of ascending levels of local councils. At the village level, there is an RWC1; at the cluster level, RWC2; and for each zone, RWC3. These are decided by elections overseen by the OPM. The RWC at each level is headed by a chairperson.

Firewood and Environmental Challenges

The conflict issue that is most significant between the host communities and the refugee population is the issue of firewood. Collection of firewood around Bidibidi is ad hoc, with undefined access rights to both communities. The daily negotiation triggers hostilities, tensions and perceptions of insecurity. Refugees must negotiate daily for access to gather firewood and biomass in the surrounding land. There are no formal land rights granted to the refugees, so there is a constant risk of violence, assault and extortion on an already traumatised population.

This firewood problem is multilayered. First, there is no designated area for the refugee community to access firewood. According to interviews, the problem is complicated by refugee women’s fear of the Aringa men from the host communities, accusing them of gender-based violence. During interviews, Aringa representatives claim their intentions are often misjudged, due to language barriers – for example, men often need the gathering area for charcoal production. While there have been consistent efforts to mitigate this problem, the issue appears unsolvable until land is clearly designated for firewood collection and/or cooking fuel is provided to the refugees.

Second, environmental degradation continues as biomass is cleared in the vicinities of the refugee settlements. Refugees are considered by the host communities to be temporary visitors, who do not respect the land or care about sustainability. Some host community members call the refugees “insensitive”. A non-governmental organisation (NGO) official explained during interviews that environmental degradation is a very big problem and a key way to solve it is to plant more trees. They have been trying to work on the problem, but need much intervention in terms of planting more trees. While members of the host communities do not relay belligerent complaints with regard to land-sharing, questions about environmental degradation prompt angry replies. Officials in the district confirmed during interviews that the refugee presence has increased Yumbe’s population by 50%. This is a sudden and monumental strain on resources. The host communities are also concerned about the grass, which is needed to feed livestock. Refugees, however, cut grass for their own use to thatch houses – or, sometimes, they burn grass in accordance with traditional customs. A senior Ugandan official remarked during an interview:12

The environment has been degraded. It’s been massive. The community needs mitigation measures to rehabilitate the environment, which is now out of control. It will cause a lot of problems. Environment has many components. There were issues of bush burning. It can destroy grass, and destroy trees. It can also cause pollution in the atmosphere. We want a comprehensive approach to be taken to mitigate issues related to the environment.

During interviews, an OPM official confirmed these challenges, suggesting that agencies should consider providing efficient cooking stoves to refugees and step up efforts to plant trees. He indicated that intervention was minimal and that the conflict between the refugees and the hosts over firewood will not stop unless an alternative is found.

Grievances over promises made by the OPM are imperative as to whether the host communities choose to be cooperative. Host representatives stress that unresolved issues between the host communities and the OPM over land use have produced a backlash against the refugee presence within the host communities. Host communities were promised livelihood programmes that are yet to arrive. This adds to the resentment towards Ugandan administrators, which negatively influences host-refugee relations. Local officials, in particular, note that the infrastructure of the area was already severely underdeveloped before the settlements were established.

Internal Politics and Dynamics

The population of Bidibidi is relatively peaceful, despite the diversity of its inhabitants. Nevertheless, there have been isolated cases of ethnic conflict in the settlement, related to the war in South Sudan. Low-level interpersonal conflict is also widely reported, due to the trauma and hardship of resettlement.

The politicisation of ethnicity has been a defining characteristic of the war in South Sudan, and this ethnic conflict has been mirrored in the settlement. Most of the settlement residents perceive their communities to be on the same “side” of the war, against the South Sudanese government. However, this is not necessarily always the case.

One major flashpoint in the refugee settlement is centred on a small population of Dinkas. Most refugees associate ethnic Dinka groups with the government of President Kiir, the leadership of the SPLA, and the ethnic Dinka Mathiang Anyoor military force deployed in parts of Equatoria in 2016. Many refugees blame these groups for numerous atrocities. As a result, Dinkas have been singled out and isolated from the rest of the South Sudanese refugee community. During interviews, it was clear that tensions over the Dinka presence have occasionally resulted in direct violence – not only in Bidibidi, but also in the Rhino camp settlement, as was the case in June 2018.

The gender disparity in Bidibidi influences both refugee interactions and domestic conflict. There are many women living in the settlement without their husbands, which often leads to personal challenges. Men come to Bidibidi to find their wives, and instead discover infidelity. War brings poverty, which often forces women into sexual exploitation to survive and support their families.13 Adultery also leads to conflicts among women and affects family dynamics. According to interviews with women and refugee leaders, significant interpersonal conflicts and domestic abuse ensue. Depression and anxiety caused by earlier traumatic events in South Sudan, as well as alcoholism and financial stress, are serious problems in the refugee settlement.14

Land Disputes

Land is an emotional and contentious topic, and issues relating to resource-sharing causes feelings of bitterness and insecurity.15 The host communities have deep cultural and emotional ties to their land, which extends beyond the issue of resources. They focus their conversations on Ugandan actors. The government and interlocutors do not seem directly concerned about the refugees and the land given to them. In contrast, the refugees interviewed are more concerned about sharing the land with the host communities. Refugees argue that the land is impossible to cultivate, either because it is too rocky or too close to livestock or too far from their home. This is not an issue between the refugees and host communities, but rather one between the host communities and Ugandan authorities,16 because the Ugandan authorities have not kept their promise of compensating the host communities for the land that was given to the refugees. As indicated previously, host communities were promised livelihood programmes that are yet to arrive. This creates further resentment and negatively affects host-refugee relations. The presence of the refugees and the issue of land is the catalyst for tensions between the Ugandan state and its citizens.

The Bidibidi settlement is located on the communal land of the Aringa people, who are governed by customary laws. In general, communal land falls under the control of the specific clan with historical claim to the area. Under this system, each clan has a designated “land chief” responsible for speaking on behalf of the community. Most of Bidibidi is on land that was not used prior to the refugees’ arrival, as it was considered unsuitable for agriculture. But this land supported hunting, livestock grazing and charcoal production critical to the livelihood of the host population.

The customary nature of land rights resulted in adjudication on an “as needed” basis, since land rights have not officially been designated. The land that forms the Bidibidi settlement was unsettled on by the host population; consequently, the refugee situation stirred underlying disputes between individuals and sub-clans over the use and boundaries of the area. These manifested in two forms of conflict:

(1) the perceived monetary benefit of land claims near the refugee sites; and (2) the negative effects on those previously using the land for livelihood purposes, primarily charcoal production, grazing and hunting. Several interviewees brought up boundary disputes between the sub-clans of Odravu and Kululu, specifically who has the authority to make decisions. These disputes have compromised relief programmes, including the building of a health facility. Claims to land rights are being waged not only by land chiefs, but also by citizens and agencies who falsely assert ownership.

Host representatives gave different responses about whether or not they were promised anything in exchange for their land. Many were frustrated, because they were not provided with “appreciation” for their generosity. The repeated use of the word “appreciation”, rather than compensation, indicated that an in-kind payment for the land was not expected. One OPM official explained that his office was constrained in its ability to fulfil all of its commitments, due to resource deficits and ambiguity over land rights. Some respondents believed that local politicians and elites were agitating the Aringa elders and land chiefs against the OPM, for their own benefit.

Competition for Resources

There is a low-intensity disagreement among the levels of local government over control of anticipated and actual aid resources that the host communities are to get 30%. The UN and OPM had set a condition that all implementing partners had to allocate 30% of all aid resources (training opportunities, livelihoods, and so on) to benefit the host communities. Representatives of all levels of local councils interviewed in Yumbe district all argued that the “30%” of aid projects destined for the host communities should be targeted to, and controlled by, the hosting village, sub-county and district respectively. The ambiguity of, and lack of transparency in, the “30% rule” has created more overt conflict over these resources. There needs to be clarification on who is entitled to what at all levels of implementation, to avoid the escalation of conflicts.

Conclusion

In general, conflict transformation focuses on relationships between parties. To achieve this, there is a need for a clear mechanism for conflict transformation – such as dialogue focusing on shared interests and resources, since the conflict seems to be focused mostly on resources such as land use and access to firewood collection. The aid resources serve to bridge, but also divide, the host and refugee populations. There are also widening gaps around the politics and grievances of hosting refugees, which could widen if left unaddressed. However, these challenges could also be an opportunity to lay the groundwork for longer-term stability and peaceful relations, with a view towards a likely long-term refugee presence in Yumbe district. The government and implementing partners should focus on clarifying their position with the host communities on land use, to avoid the host communities blaming the refugees. There is also a need to train refugees on Ugandan laws governing land and conflict management. Special attention must be paid to women – most of the refugees are women, and issues that affect their daily lives must be prioritised.

There are some significant positive findings from the Bidibidi settlement. The Ugandan government and aid agencies responded to an emergency crisis of unprecedented scale, all the while negotiating local politics and mobilising emergency relief. The South Sudan refugees, with some notable exceptions, have integrated relatively peaceably. There are a number of local and international NGOs working side by side to support both the refugees and host communities to cope with daily challenges. This is a window of opportunity for collaboration between relevant stakeholders involved in education, livelihoods and conflict management. There is a small-scale butter trade going on between the refugees and host communities, especially between the women. Refugee women exchange food for charcoal or firewood from the host community women. This creates a sense of common need for women, which can further improve relationships.

Some recommendations to improve stability and relations between all communities, and to prevent further conflict in Bidibidi and its surrounds, are:

- OPM should engage in talks with landowners and clan chiefs over land rights and The chiefs and landowners are so powerful that they can be spoilers of peace. The community listens to them and trusts them. Government officials and partners should use these local leaders as connectors of peace to build relationships between the host communities and refugees.

- Due to the scarcity of natural resources and its impact on the environment, the Ugandan government and partners should advocate to donors to scale up existing projects for alternative energy. The firewood issue needs to be resolved to avoid ongoing conflict and intimidation, by providing alternative cooking fuels that can replace wood fuel and charcoal, as well as developing skills for the construction of Three types of cooking fuel that can be explored are briquettes, pellets and ethanol.

- There should be more capacity building for RWCs and local committees to hold local courts for matters between hosts and refugees in terms of alternative dispute mechanisms and legal However, there is also a need for awareness campaigns to ensure that the local courts avoid adjudicating beyond their jurisdiction.

- Implementing partners should use the “Do No Harm” conflict-sensitive approach, which focuses on reducing the negative effects of aid on war and conflict17 so as to minimise the drivers of conflict and focus on connectors of peace.

- Communal land ownership between chiefs and sub-clan members should not be These are elders elected by the community to be the custodians of community properties, and the government needs to work with them for access to any community resources. Importantly, refugees need to be provided with land for cultivation and resources for education on land use.

- Many refugees are still living with the effects of the traumatic experience of war, which can be triggered at any time. It is important to allocate resources such as counselling services to respond to the trauma of the refugee population. Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders has already phased out its emergency response in Yumbe, but there is still the need for such services.

Endnotes

- Lederach, John Paul (2003) The Little Book of Conflict Transformation: Clear Articulation of the Guiding Principles by a Pioneer in the Field. Pennsylvania, USA: Good Books, pp. 14, 17.

- UNHRC (2018) ‘Refugees and Asylum-seekers from South Sudan, February 2018’, Available at: <http://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/southsudan?id=1378> [Accessed 4 July 2018].

- The Republic of Uganda (2016) ‘National Population and Housing Census (2014) – Main Report’, Available at: <https://www.ubos.org/onlinefiles/uploads/ubos/NPHC/NPHC%202014%20FINAL%20RESULTS%20REPORT.pdf> [Accessed 3 July 3018].

- World Vision Uganda (2017) ‘Uganda Now Home to a Million Refugees and Asylum-seekers’, Available at: <https://www.wvi.org/uganda/article/uganda-now-home-million-refugees-and-asylum-seekers> [Accessed 6 July 2018].

- United Nations (1951) ‘UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951’, Available at: <https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetailsII.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=V-2&chapter=5&Temp=mtdsg2&lang=en> [Accessed on 10 June 2018].

- Mulumba, Deborah (n.d.) Humanitarian Assistance and its Implication on the Integration of Refugees in Uganda. Unpublished report, Makerere

- World Vision Uganda (2018) ‘Refugees and Asylum-seekers from South Sudan – Total as for February 2018’, Available at: <http://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/southsudan?id=1378> [Accessed 10 July 2018].

- Mischnick, Ruth and Bauer, Isabella (2009) Yumbe Peace Process. Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 1–2.

- Inter-Agency Regional Analysts Network (2017) ‘Bridging the Gap: Long-term Implications for South Sudanese Refugees in West Nile, Uganda’, Available at <https://www.actionagainsthunger.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/bridging_the_gap_-_final.pdf> [Accessed 6 August 2018].

- Hodgson, Camilla (2018) ‘Satellite Images Show How the Tiny Ugandan Village of Bidi Bidi Became the World’s Largest Refugee Camp’, Business Insider, 23 January, Available at: <https://www.businessinsider.com/birdi-satellite-images-refugees-south-sudan-2018-1>[Accessed 25 July 2018].

- Ibid.

- Interview with a senior Ugandan official, conducted by author, in Yumbe (2018).

- Sjoberg, Laura (2014) Gender, War and Cambridge UK: Polity Press, pp. 35–36.

- Amnesty International (2016) ‘Our Hearts Have Gone Dark’, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AFR6532032016ENGLISH.PDF> [Accessed 3 June 2018].

- Barigaba, Julius (2017) ‘Shrinking Land Opens New Challenge Facing South Sudanese Refugees’, The East African, 10 September, Available at: <http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/news/Land-challenge-facing-South-Sudanese-refugees/2558-4089756-2o81rw/index.html> [Accessed 15 September 2018].

- Vogelsang, Ard (2017) ‘Local Communities’ Receptiveness to Host Refugees: A Case Study of Adjumani District in Times of a South Sudanese Refugee Emergency’, Thesis, Utrecht University Repository, Available at: <https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/353562> [Accessed 5 August 2018].

- Anderson, Mary (1999) Do No Harm: How Aid can Support Peace or War. Boulder CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.