Introduction

The 14 December 2016 announcement of a National Dialogue Initiative in South Sudan by the country’s leader, President Salva Kiir Mayardit, although met with divergent reactions locally, regionally and internationally, presented a rare and convenient opportunity for South Sudanese to engage, build peace and reconcile. This came against a background of cross-country intercommunal violence, political power struggles, national governance challenges, economic instability, massive internal displacement of citizens, disunity and disintegration, which had been aggravated by the near-collapse of the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) in July 2016, following the resumption of fighting between forces loyal to Kiir against those aligned to the then-vice president and leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO), Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon.

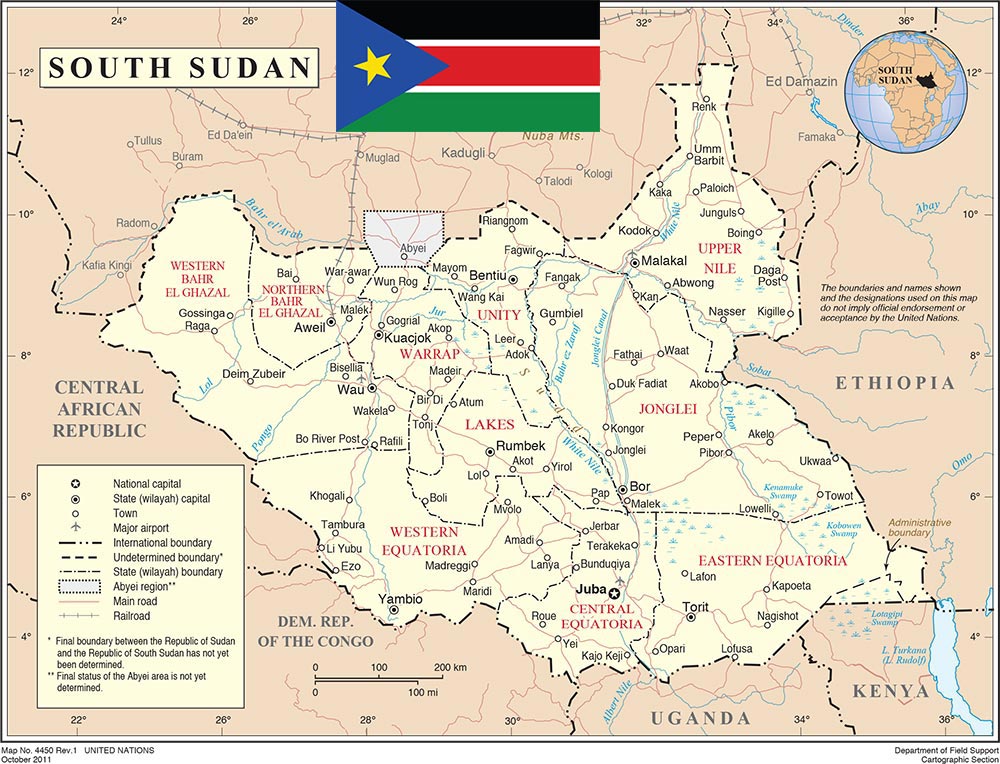

The National Dialogue consultation process started in early November 2017 at local and regional level and is envisaged to end in mid-2018. This process is paving the way for regional dialogue conferences, which will culminate in the National Dialogue Conference in late 2018. Accordingly, it may be timely and worthwhile to take stock of progress made so far, identify current and possible obstacles to the process, and recommend ideas that may assist to sustain the National Dialogue. Granted, a lot of ground is yet to be covered, as the National Dialogue consultations intend to cover each of South Sudan’s 32 states, in addition to refugee and international outreach consultations in 15 countries in Africa, Australia, Europe and North America.1 An assessment of progress and challenges at this stage will allow for early diagnosis of impediments that may hamper and encumber the smooth progression of the process, and thereby provide room for amends.

Contextualising South Sudan’s National Dialogue Initiative

The initiation of the National Dialogue in South Sudan may be traced to the outbreak of fighting between Kiir and Machar’s presidential guard personnel at the presidential palace in Juba on the night of 6 July 2016. This fighting later spread to other parts of the country. The fight was triggered by disagreements within the presidential guard following alleged orders to disarm Machar-aligned Nuer members due to an alleged coup plot.2 This had been preceded by continued factional struggles within the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). This contestation for power had become rife in 2013 as the country approached the general elections scheduled for 2015, with the senior leadership openly criticizing Kiir and declaring their intentions to contest him in the elections.3

Since then, the Transitional Government of National Unity’s implementation of the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) – which had sought to resolve the conflict in South Sudan following the initial outbreak of violence on 13 December 2013 – has been minimal. After political tensions and the clashes that followed when Machar and other influential opposition figures fled the country into exile, there was a general deterioration of peace, security and stability in South Sudan as conflict intensified across the country.

Thus, the National Dialogue Initiative came at a time when the political and economic situation in South Sudan had been so dire that it warranted more sustainable interventions to restore stability. Even Kiir, in his National Dialogue Initiative speech, acknowledged without denial that South Sudanese people had been distressed by the continued political conflict and “drastically declining economy”. Accordingly, the time was ripe to engage in a national dialogue process to “end violent conflicts in South Sudan, reconstitute national consensus, and save the country from disintegration and usher in a new era of peace, stability and prosperity”.4

Structural Framework of the National Dialogue Initiative

It is imperative to examine the structural framework that was put in place to facilitate the National Dialogue process. In a way, this constitutes part of the broader challenges that may threaten the efficacy of the dialogue. The structure comprises the National Dialogue Leadership (nine members), the National Dialogue Steering Committee (NDSC) (97 members), the National Dialogue Secretariat (13 members), and the National Dialogue stakeholders and partners.5

The National Dialogue Leadership comprises two co-chairpersons: Angelo Beda and Abel Alier Kwai. Gabriel Yoal Duk, Bona Malual and Francis Mading Deng serve as the deputy co-chairperson, rapporteur and deputy rapporteur/spokesperson respectively, whilst the other members of the leadership are Mary Bensensio Wani, Elizabeth Achan Ogwaru and Lilian Riziq. The role of the leadership is to set policy and strategy, as well as to carry out official communication with political and diplomatic leaders.

The NDSC has 97 members who serve in 15 subcommittees: one subcommittees for each of the 10 states of South Sudan; one subcommittee for the capital city, Juba; two area subcommittees for Pibor and Abyei; one Subcommittee for Refugees and International Outreach; and one subcommittee for security matters.6 The mandate of the NDSC is to organise consultation forums and document input from forum participants, and report on this to the Steering Committee. On the other hand, the National Dialogue Secretariat, which is made up of 13 members, has the role of vetting the work of the NDSC and leadership, as well as communicating to the public and the press.

The stakeholders to the National Dialogue are South Sudanese citizens within and outside its borders, the government, political parties, civil society organisations (CSOs), academia, think-tanks, and national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

The composition and configuration of such important structures define and shape their sustainability, as well as people’s confidence and trust in the National Dialogue process. This will be assessed below.

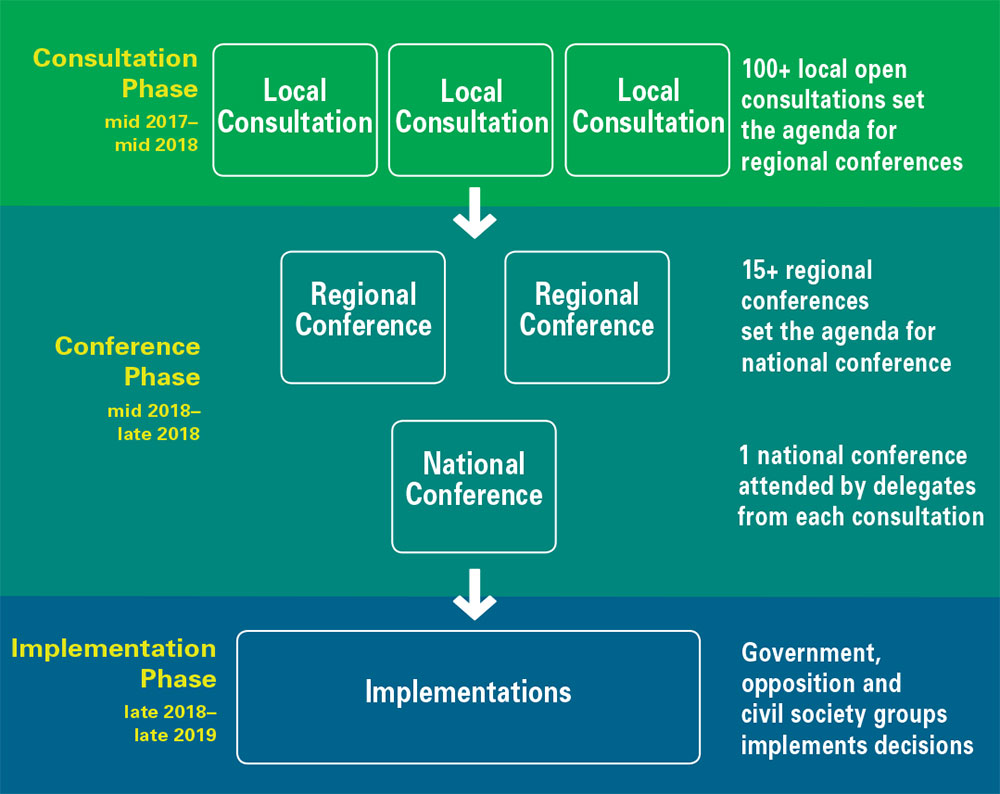

The Envisaged National Dialogue Milestones

Local dialogue consultations are envisaged in each of South Sudan’s 32 states. These will feed into regional conferences in the capitals of all the large states, and will be followed by a national conference. All in all, the National Dialogue will conduct 80 local consultation forums, international outreach forums in 15 countries around the world, 20 regional consultation forums, and one national consultation forum.7 Implementation of the dialogue outcomes has been set for late 2018 to late 2019. The milestones for the National Dialogue have also been set, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Timelines and phases for the South Sudan National Dialogue agenda8

Notable Progress and Milestones Achieved

A fact that cannot be disputed is that considerable effort has been invested into the National Dialogue process, and there are notable achievements that have been recorded to date by the National Dialogue institutions working with the various stakeholders.

The first achievement is national acceptance of the concept. To some extent, almost all South Sudanese have embraced the National Dialogue in principle, although differences still exist with respect to timing and implementation modalities, among other issues of contention. There appears to be a profound acknowledgement by a substantial portion of the population that there is need to engage in a national conversation to manage their differences, renegotiate the social contract and reach common ground on the way forward to secure lasting peace, stability and prosperity. This is evidenced both by attendance at the national and regional consultation forums and public opinion presented in various South Sudanese media platforms.

Second, the government – to its credit – was able to set up the structure and organisational framework to operationalise the National Dialogue. The National Dialogue Leadership, NDSC and subcommittees, and National Dialogue Secretariat are all in place. Whilst Kiir had initially self-appointed himself as the patron of the NDSC in 2016, his decision in June 2017 to recuse himself by relinquishing his patronage of the committee brought some semblance of independence and credibility to the institution. Although the committee appears to be regionally balanced, there are still questions raised over the selection criteria – and, consequently, the extent of independence of the NDSC members. This undoubtedly erodes some of the committee’s credibility. A case in point is that of those who turned down their appointment to the NDSC, such as Roman Catholic Church Bishop Paride Taban, and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement Former Detainees (SPLM-FDs) officials Rebecca Nyadeng de Mabior and Kosti Manibe Ngai. They cited various reasons, including disagreement on the terms of reference, and the absence of “level ground for dialogue, and lack of pre-consultation and transparency”.9

Third, to a considerable extent, the National Dialogue institutions have managed to secure regional and international buy-in to the process. In principle, the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), African Union (AU) and the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) have all expressed their support of the National Dialogue process in South Sudan. However, their support may be interpreted as equivocal and non-committal, as they have consistently stressed that they would support a National Dialogue process that is all-inclusive, independent, transparent and constructive, whilst underscoring the fact that the dialogue initiative should complement rather than supplant the ARCSS.10 For instance, the IGAD Council of Ministers emphasised the need for the South Sudan NDSC to reach out to the opposition and ensure that the National Dialogue was conducted in an “inclusive, genuine and transparent manner”.11 Similarly, the AU Peace and Security Council, in its Communiqué of the Ministerial Meeting held in September 2017 relating to South Sudan, reiterated that “the National Dialogue must be all-inclusive, independent and transparent to ensure the credibility and public acceptance of its outcomes”. It added that the process “should complement and not be perceived as replacement for the full implementation of the ARCSS and the Revitalization process led by the IGAD Council of Ministers”.12

Fourth, progress has been made in terms of conducting the actual consultations. To its credit, the NDSC (working with its 15 subcommittees) has already managed to conduct local consultation forums, regional consultation forums and international outreach forums in Uganda and Kenya. In the period between early November 2017 and early January 2018, local and regional dialogue consultation forums have been conducted in several districts in Yei River State, Central Upper Nile State, northern Bahr El Ghazal, the Lakes states, the eastern Equatoria region, Torit, Imatong State, Jubek State, Malakal, Renk and Terekeka State.13 In Kenya and Uganda, the Subcommittee for Refugees and International Outreach carried out dialogue consultation forums in the capital cities and refugee settlements in the two countries between 13 November and 1 December 2017. Nonetheless, the pace of coverage is behind schedule, considering the stipulated time frame.

Pitfalls of the National Dialogue Initiative

Notwithstanding some progress achieved thus far, the National Dialogue process in South Sudan faces its own challenges, and its success continues to be under threat from both internal and external factors. Drawing from an analysis of the situation in South Sudan, an evaluation of various reports emanating from the dialogue consultation forums conducted so far, and observation of live recordings of some of the consultation sessions, these challenges relate to the exclusion or non-involvement of key stakeholders to the conflict; non-existence of a conducive environment for peaceful dialogue; mistrust and misperceptions by some stakeholders to the conflict; low levels of attendance during dialogue consultation forums; shortage of resources; and the prevalence of fear among some citizens. Whilst some of these challenges can be addressed with ease, a number of them appear to be complex.

Perhaps the most difficult factor is that some key stakeholders to the dialogue have excluded themselves from the process. Given the nature of the South Sudanese conflict, any dialogue process that excludes the opposition parties and rebel groups may be counterproductive. Without engaging influential figures who are instrumental in the power matrix that is perpetuating the conflict, it is difficult to achieve peace in South Sudan. Whilst agreeing to the dialogue in principle, almost all the influential opposition leaders – SPLM-FDs, SPLM-IO, the National Democratic Movement (NDM), South Sudan National Movement for Change and several other parties – distanced themselves and their followers from the dialogue. This was done on the basis that the dialogue lacked pre-consultation engagements, the inappropriateness of the venue, concerns over the proposed methodology or implementation modalities, inclusivity, transparency, impartiality and that there is an absence of an enabling security environment.14

Although Kiir decided to continue the dialogue process without the opposition, having failed to meet their preconditions, the entire National Dialogue becomes a monologue and risks not achieving its intended outcome. As Paffenhholz et al point out in What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues?, using case studies of 17 national dialogues in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America, one of the success factors of national dialogues is the inclusion of key national elites, both unarmed and armed significant opposition parties and, occasionally, the military, over and above other representative groups.15 The main goals of the South Sudanese dialogue are to end all forms of violence, re-establish unity, address issues of diversity, settle historical disputes and further national healing and peace – yet some of the major players and parties to the conflict are uninvolved. Above all, the resolutions of the National Dialogue process are expected to be binding on all stakeholders to the conflict in South Sudan, against a background of exclusivity. Experiences in the recent past should remind the South Sudanese leadership that non-inclusive peace processes are unsustainable. For example, the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities, Protection of Civilians and Humanitarian Access, signed by the government and some opposition parties on 21 December 2017 in Addis Ababa, has already been violated several times16 – largely because it excluded some key opposition players, such as Machar.

Another critical constraint is the absence of a peaceful and conducive environment to maintain and sustain a genuine National Dialogue consultation process. This has been echoed by the opposition. It may be argued that the initiation of a dialogue process will bring an end to the ongoing hostilities, but that may only be the case if all the parties to the conflict have consented to the dialogue.

As it stands, the political, social and economic situation in South Sudan is not conducive for genuine dialogue within the country. Reporting on the economic developments and security situation in South Sudan for the period between early September and mid-November 2017, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) noted that the country faced “serious economic challenges”, characterised by triple-digit inflation and an annual consumer price index of 131.9%. In addition, there were clashes between SPLA forces and the pro-Machar SPLM/A-IO, as well as intercommunal violence in regions such as the Lakes, Greater Bahr el-Ghazal, Greater Upper Nile and Greater Equatoria.17 Relating to the sociopolitical status quo, the UNSC Report for December 2017 indicated that 1.86 million people had been displaced by conflict across South Sudan, with an additional 2.1 million people having fled as refugees to neighbouring countries, including Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Uganda, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda, among others.18 The report added that an estimated 4.8 million people faced severe food insecurity, and projected that the number was likely to rise to 5.1 million people by the start of 2018.19 As of 11 January 2018, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) had received 204 172 displaced South Sudanese civilians at its bases in the Central Equatoria, Unity, Upper Nile, Jonglei and Western Bahr El Ghazal regions due to continued fighting, violence and intercommunal clashes.20

Perhaps there was merit in the proposals tabled by the opposition parties for inclusive pre-dialogue commencement engagements between the government and armed and unarmed opposition parties to commit to a mutually agreed ceasefire. Although well intentioned, the unilateral ceasefire declared by Kiir will remain ineffectual. Ceasefire declarations by all parties to the conflict would have had a greater prospect of soliciting the much-needed cooperation, commitment and accountability from all parties in terms of implementation. Such an approach would create a conducive environment where citizens are free and secure to participate in dialogue.

Mistrust, negative perceptions and misperceptions are also part of the challenges faced by the national dialogue process. Some citizens are still sceptical and suspicious of the motive, intentions and goodwill behind the National Dialogue Initiative. As the Report of the UN Secretary-General on South Sudan observed, “[M]any stakeholders perceive that the Government is using the national dialogue to override the implementation of the peace agreement [ARCSS].”21 In the end, citizens and stakeholders lose confidence in the whole process, as they perceive elite manipulation. This may explain the reason why the attendance figures, as reported by the NDSC, are not very encouraging. This has also been coupled with the fear of reprisals, which still exists among some citizens whenever they are given the platform to discuss National Dialogue agenda issues. For example, the Subcommittee on Refugees and International Outreach reported that “[t]here was a sense of misinformation and apprehension of what exactly was the mission of the National Dialogue in Kenya”.22 This definitely affected the quality of deliberations, as well as the outcome of the dialogue sessions. However, it is encouraging to note that in a number of consultation sessions, citizens were reported to be engaging in frank, open, honest and fearless discussions, as observed by the NDSC.

The resource factor cannot be underestimated, as it has potential to undermine the scope of coverage and to pose logistical impediments. The NDSC admitted from the beginning that the government has no capacity to fund the dialogue process.23 Whilst donors – the governments of Japan and Germany, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and UNMISS – have plausibly committed to and still assist with funds, resources, technical and governance support, there should not be over-reliance on external funding sources for such an important national process, as this may have its own demerits in terms of process ownership and sustainability.

Further, there is a possibility that the National Dialogue process in South Sudan may be yet another initiative that will trap the country in the never-ending conflict cycle, if the South Sudanese leadership refuse to learn from their past mistakes and calls from the UN, AU, IGAD and its immediate neighbours. The consistent call has been that the South Sudanese leadership should exhibit political will and the maturity to refuse to be ensnared in the unproductive politics of a power struggle, implement all peace agreements as per commitment, respect the rule of law, establish and maintain vibrant institutions of good governance, and lead by example in cultivating and fostering a culture of peace, tolerance and unity in diversity. Whilst Kiir stated that the National Dialogue process will ultimately culminate in the adoption of resolutions emerging from the consultations, which will then be forwarded to “different processes such as constitutional conference, peace, healing and reconciliation, et cetera, for consideration and inclusion therein”,24 the implementation of such resolutions by the leadership in power – based on the leadership’s governance track record and the South Sudanese political culture – may be possible, but highly improbable. In any case, all the views that are emerging from the consultations (such as separation of powers, unity in diversity, accountability in governance, ending power struggles, anti-corruption, broad-based economic development, de-ethnicisation of politics and governance, human rights observance, among others) are not new – they are eloquently expressed and enshrined in the Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan, as well as the ARCSS. Unfortunately, if the past mistakes are not acknowledged and addressed, there may be no guarantee or political assurance that the outcome of the dialogue process (resolutions) will be respected and implemented, and this will signal a conflict cycle trap.

Conclusion and Way Forward

Based on the analysis of the progress and pitfalls of the National Dialogue in South Sudan, it is evident that whilst there are notable milestones achieved, the dialogue faces a number of challenges that may affect not only the quality of its output, but also threaten the ultimate attainment of the initiative’s overall purpose. As stated, it is difficult to envisage a successful dialogue that excludes the key parties to the conflict. As a way forward, efforts should be made to innovatively address the conditions tabled by the opposition parties, to ensure that all opposition parties and armed groups are part of the dialogue. On the part of SPLM-IG and all opposition parties in South Sudan, there is need for a paradigm shift from destructive combative, hostile and confrontational politics towards politics of constructive engagement, national convergence, tolerance, consensus-building and cooperation, punctuated by a commitment to agreements, goodwill, constitutionalism and respect of the rule of law – and good governance rather than empty rhetoric, pretence and the selfish pursuit of political power.

Endnotes

- South Sudan National Dialogue Secretariat (2017a) ‘Consultation Events Structure’, Available at: <https://www.ssnationaldialogue.org/events/event-consultation-structure/> [Accessed 21 December 2017].

- Vhumbunu, Clayton Hazvinei (2016) Conflict Resurgence and the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan: A Hurried and Imposed Peace Pact? Conflict Trends, 2016 (3), p. 5.

- Ibid, p. 5.

- Republic of South Sudan (2017a) ‘Speech of His Excellency the President Announcing the Commencement of National Dialogue’, 14 December 2016, Available at: <https://paanluelwel2011.files.wordpress.com/2016/12/president-kiir-address-to-the-nation-the-call-for-national-dialogue-initiative-in-south-sudan.pdf> [Accessed 20 December 2017].

- South Sudan National Dialogue Secretariat (2017a), op. cit.

- Republic of South Sudan (2017b) ‘Republican Order No. 08/2017 for the Reconstitution of the National Dialogue Steering Committee 2017 A.D’, 25 April 2017, Available at: <https://paanluelwel2011.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/presidential-decree-reconsttitution-of-the-national-dialogue-steering-committee-april-25-2017.pdf> [Accessed 2 December 2017].

- South Sudan National Dialogue Secretariat (2017a), op. cit.

- South Sudan National Dialogue Secretariat (2017b) ‘How National Dialogue Works’, Available at: <https://www.ssnationaldialogue.org/how-national-dialogue-works/> [Accessed 22 December 2017].

- Radio Tamazuj (2017) ‘Kosti Manibe Declines Appointment into National Dialogue Committee’, 30 April, Available at: <https://radiotamazuj.org/en/news/article/kosti-mabibe-declines-appointment-into-national-dialogue-committee> [Accessed 5 January 2018].

- United Nations Security Council (2017a) Report of the Secretary General on South Sudan (Covering the Period from 2 September 2017 to 14 November 2017), 1 December, p. 3.

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (2017) ‘Communiqué of the 58th Extra-Ordinary Session of IGAD Council of Ministers on the Situation in South Sudan’, 23–24 July, Juba, South Sudan, Available at: <https://igad.int/attachments/article/1599/Communique%20of%20the%2058th%20Extra-Ordinary%20Session%20of%20IGAD%20Council%20of%20Ministers%20on%20South%20Sudan.pdf> [Accessed 3 January 2018].

- African Union (2017) ‘Communiqué, Peace and Security Council, 720th Meeting at the Level of Ministers’, PSC/MIN/COMM. (DCCXX), 20 September, New York, USA, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-720-comm-south-sudan-20-09-2017-new-york.pdf> [Accessed 29 December 2017].

- South Sudan National Dialogue Secretariat (2017c) ‘National Dialogue Updates’, Available at: <https://www.ssnationaldialogue.org> [Accessed 2 December 2017].

- Sudan Tribune (2017) ‘S. Sudan Opposition Sets Condition for “Meaningful” Dialogue’, 2 May, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article62335> [Accessed 7 January 2018].

- Paffenhholz, Thania, Zachariassen, Anne and Helfer, Cindy (2017) What Makes or Breaks National Dialogues? Inclusive Peace and Transition Initiative Report, The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, October, p. 9.

- United Nations Mission in South Sudan (2018a) ‘Joint Statement by the Chairperson of the African Union and the Secretary-General of United Nations on the Situation in South Sudan’, 17 January, Available at: <https://unmiss.unmissions.org/joint-statement-chairperson-african-union-and-secretary-general-united-nations-situation-south-sudan> [Accessed 13 January 2018].

- United Nations Security Council (2017a), op. cit., pp. 4–5.

- United Nations Security Council (2017b) ‘December 2017 Monthly Forecast for South Sudan’, 30 November, Available at: <http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2017-12/south_sudan_38.php> [Accessed 29 December 2017].

- Ibid.

- United Nations Mission in South Sudan (2018b) ‘UNMISS POC Sites Update No. 187’, 16 January, Available at: <https://unmiss.unmissions.org/unmiss-poc-sites-update-no187> [Accessed 18 January 2018].

- United Nations Security Council (2017a), op. cit., p. 1.

- South Sudan National Dialogue Secretariat (2017) ‘Media Briefing on Consultations in Uganda and Kenya’, press release, 5 December, Available at: <https://www.ssnationaldialogue.org/press-release/media-briefing-on-consultations-in-uganda-and-kenya/> [Accessed 10 January 2018].

- Republic of South Sudan (2017c) ‘National Dialogue Steering Committee (NDSC) Remarks by the RT Hon Angelo Beda, Co-Chair on the Occasion of the Launching and Swearing In of the National Dialogue Steering Committee’, 22 May, Available at: <https://www.ssnationaldialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/Hon-Angelo-Beda-speech-on-May-22.pdf> [Accessed 15 January 2018].

- Republic of South Sudan (2016) ‘South Sudan National Dialogue Concept Note’. December, Available at: <https://www.ssnationaldialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/Concept-Note-of-SSND-by-President-South-Sudan-National-Dialogue-Final.pdf> [Accessed 18 January 2018].