Introduction

Over the past three decades, national dialogue has increasingly been recognised as a mechanism for conflict resolution, peacebuilding and a viable framework for expanding the space for political participation and accommodation. Although widely recognised as a nationally owned process, the international community, regional and, more often than not, subregional organisations – depending on the nature and contextual dynamics of conflicts – play an important role in supporting national dialogue processes. This is true with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a subregional organisation with over two decades’ experience in mediating and supporting peace processes in the West African subregion. Whilst regional integration was the singular purpose of ECOWAS’s establishment, political conflicts and instability in the 1990s – and the subsequent need to evolve mechanisms and structures that encourage the peaceful resolution of intrastate and interstate conflicts through good offices, conciliation, mediation and other methods of peaceful settlement of disputes1 – became the impetus for ECOWAS to refocus its attention on developing a regional architecture for peace and security.

This article2 provides an overview of ECOWAS’s efforts at supporting national political dialogue processes in the subregion through its numerous declarations, statements and field interventions, with a focus on Guinea. It is important to note that as a subregional organisation promoting peace, security and regional stability, ECOWAS constitutes one of the pillars of the African Union (AU) Commission’s Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), and works in partnership, cooperation and collaboration with the AU, United Nations (UN) and other relevant international actors in promoting peace processes in its member states.

Contextualising National Dialogue: Definition and Contending Issues

Preventing conflict means “building relationships between people and communities so that they can talk about their problems, in order to prevent those problems from escalating into violence”.3 Dialogue, an essential tool of communication, has been defined as “an interactive conversation between one or more sides working together towards a common understanding”.4 “It is a process of people coming together to build mutual understanding and trust across their differences, and to create positive outcomes through conversation.”5 As part of a wide range of peacemaking approaches, “dialogues are not only to resolve conflicts but more importantly to heal wounds, reconcile groups, build confidence and trust in institutions and in people towards social cohesion and national development”.6 Conceived in this sense, it is argued that “dialogue can only have positive effects when both sides are willing to take into account what the other side considers as its vital interest”.7 Dialogue helps to foster relationships and build an inclusive consensus among a wide group of actors.8

Dialogue can take place at various levels in a given society – at the local and community level, as well as at the national level. Equally, dialogues can come in various forms, among which are high-level or summit dialogues, involving the top leadership of contending sections of the population, often initiated or mediated by the international community; civil society and community-based organisations’ facilitated dialogues; multilevel dialogues, involving various levels of society in an effort to engage citizens in building sufficient national consensus on critical challenges; and political dialogues, which take place as an indispensable aspect of planning for peacebuilding, state-building and development,9 or as a framework for addressing threats in a society that can cause a lapse or relapse into violent conflict.10 These four approaches are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary, with each type having its own advantages and limitations.11

National dialogues, however, have a distinct format, characterised by their national scope and purpose. They have been defined as “nationally owned political processes aimed at generating consensus among a broad range of national stakeholders in times of deep political crisis, in post-war situations or during far-reaching political transitions”.12 In terms of their scope, national dialogues address issues of national relevance, such as power-sharing during peacebuilding processes, preparations for national elections, and the drafting of new constitutions.13 With regard to their purpose, national dialogues aim to restore broken state–society relations and to work on a viable social contract that allows for participatory state and nation-building.14 National dialogues are expected to establish a minimum consensus among all relevant stakeholders at a national level on ending hostilities, and pave the way for creating legitimate state structures of governance and institutions accountable to the public. This means that national dialogues are “expected to be participatory and to include the main political stakeholders, the conflicting parties, as well as societal groups such as ethnic and religious minorities, and civil society representatives”,15 including marginalised populations such as women and the youth.

We understand that national dialogues are nationally owned processes. As Giessmann states: “While the inception of a National Dialogue may be brokered or supported by external mediators – such as the UN – the process of a National Dialogue must be convened, owned and driven by its national stakeholders.”16 ECOWAS’s initiatives at supporting national dialogue processes do not deviate from this key defining element of national dialogue as a tool for managing complex political changes and political transitions, or deepening inclusive and participatory politics in all of its member states. It is within this defining element of national dialogue that ECOWAS works to facilitate and create spaces for member states to dialogue over a broad range of issues or specific issues, as the case may be, through the tools of preventive diplomacy, mediation and good offices. However, it is important to emphasise that national dialogues are only one way to address political crises and violent conflicts. “Change processes, whether peace processes, political transitions or processes to prevent or manage a political crisis, tend to incorporate a range of different methods and mechanisms, including mediation and negotiation.”17 Practitioners agree that “dialogue is not a substitute for negotiation and mediation in conflict situations”.18 Rather, it is “an essential part of conflict resolution and prevention processes, wherein the goal is to build sustainable peace”.19

Some of the contentious issues around which individuals and groups agitate for dialogue in ECOWAS member states often relate to access to political power; demands for inclusive and participatory politics; demands for power (re)configurations, based on regional or ethnic balance; demands for equitable and fair distribution of national resources; and political and economic systems restructuring and reforms, including demand for decentralisation of political power and autonomy. Elections and electoral processes equally generate controversies around which national political dialogues are often convened to resolve. Such controversies may revolve around political power tussles between incumbent presidents/prime ministers and opposition leaders; (dis)qualifications of candidates for elections; disagreement on the electoral code, voters’ register and timetable for elections; and questions around the independence and/or composition of the electoral management bodies. There are also demands for national political dialogues over constitutional and institutional issues.

The section that follows examines ECOWAS’s support to Guinea’s political dialogue processes.

ECOWAS’s Support to Political Dialogue Processes in Guinea

Guinea is an important member state of ECOWAS and played an active stabilisation role in the political crisis of the Mano River region in the 1990s and early 2000s. The current president, Alpha Condé, is the ECOWAS-appointed mediator in the ongoing political and institutional crisis in Guinea-Bissau. Guinea has, however, experienced its own internal political crisis from 2007 to 2010, mainly caused by the uncertainty surrounding former president Lansana Conté’s succession, culminating in a military seizure of power on 23 December 2008 by the National Council for Democracy and Development (CNDD) under the leadership of Captain Moussa Dadis Camara. Acting in conformity with the provisions of its relevant legal and normative instruments and protocols, ECOWAS rejected the coup, and suspended Guinea from participating in meetings and all decision-making bodies of the community. However, it negotiated with the CNDD for a return to constitutional order by establishing a National Transition Council under a transitional president, which worked towards the realisation of a return to democratic rule through the conducting of presidential elections in November 2010 in which members of the CNDD – including its leader, Camara – were not allowed to stand for elections.20

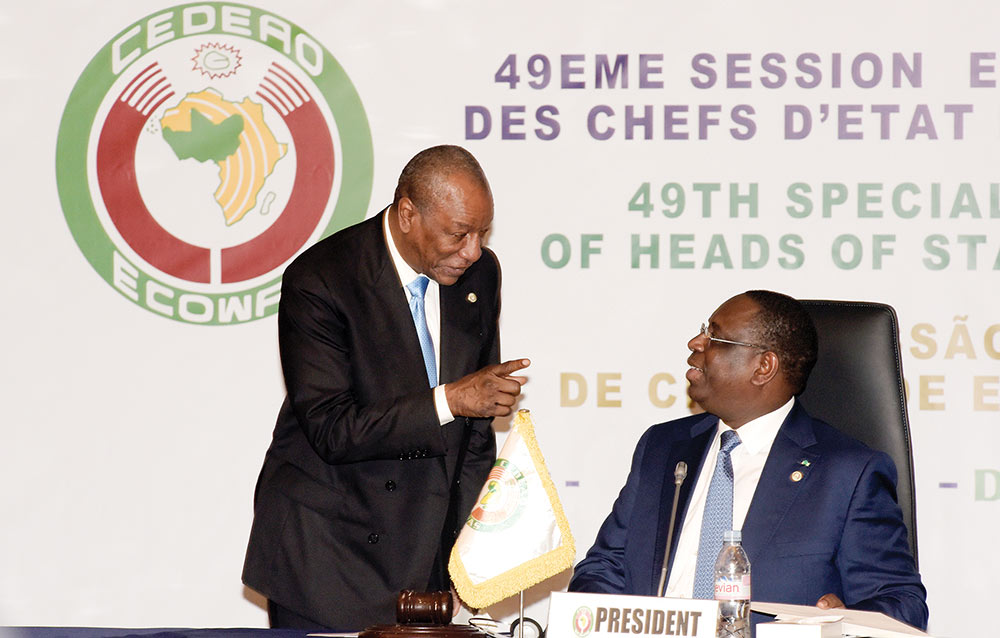

At the onset of the 2007–2010 political crisis in Guinea, ECOWAS initially appointed former president of Nigeria, Ibrahim Babangida, as special envoy for the Guinea crisis, and tasked him to work with Guinean political actors and stakeholders for the promotion of political dialogue towards returning normalcy to the country.21 At its Extraordinary Summit of Heads of State and Government held on 17 October 2009, ECOWAS officially announced former president of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, as its facilitator in the Guinea crisis. It expressed its strong support for his mediation efforts, among other things urging him to take all appropriate steps to re-establish dialogue among the Guinean political actors towards the establishment of the then-transitional authority, to ensure a short and peaceful transition to constitutional order through credible, free and fair elections.22 ECOWAS had mobilised international support for the establishment of the International Contact Group on Guinea (ICG-G), which served as a constructive platform for political dialogue between the CNDD and other stakeholders in Guinea. This led to the holding of elections in 2010, in which Condé, the current president, defeated Cellou Dalein Diallo in the final round on 7 November 2010.

Despite Condé’s victory and the country’s successful completion of the transition to democracy in 2010, Guinea needed a post-transition national political dialogue to address critical unresolved issues. Therefore, it was not surprising that in the lead-up to the presidential elections of 2015, contentious issues were raised. These issues revolved around the ordering of elections; the composition and independence of the electoral commission, Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI); and the unresolved issue of the special delegations that the president had appointed to oversee the administration of local councils/districts following the expiration of their mandate – all became important sources of tension and political deadlock, resulting in violent protests, killings and the destruction of property.

On 11 March 2015, the CENI released the electoral calendar, fixing the holding of presidential elections for 11 October 2015 and local elections by the end of the first quarter of 2016. The electoral calendar was vehemently opposed by the opposition, which preferred the holding of local elections before the presidential elections.23 Amidst growing political tensions and uncertainty, ECOWAS, at its 47th Ordinary Session of the Authority of Heads of State and Government held on 19 May 2015 in Accra, Ghana, emphasised the “need for dialogue among the political stakeholders in Guinea” and urged them to “systematically use dialogue to achieve the consensus necessary for the electoral process”24 to move forward. The ECOWAS Authority subsequently directed the ECOWAS Commission “to facilitate the dialogue between the government and opposition” and “welcomed actions taken by the President of the Commission to dispatch a high-level mission to Guinea to aid the achievement of consensus among stakeholders on the conduct of the elections and preservation of peace in the country”.25 On 25 May 2015, Condé directed his prime minister to engage with opposition leaders in dialogue to put an end to the deadlock. However, the president emphasised that the dialogue must be purely an inter-Guinean political dialogue process. This is instructive in the sense that best practice indicates that “while the inception of a National Dialogue may be brokered or supported by external mediators… the process of a National Dialogue must be convened, owned and driven by its national stakeholders”.26

In June 2015, four months before the scheduled elections, an Inter-Guinean Political Dialogue process was launched, with international partners – notably the UN, ECOWAS, the European Union (EU), the International Organization of the Francophonie (OIF), the United States and France’s ambassadors in Guinea – serving as observers of the dialogue process. After about 10 days of initial talks, assisted by the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), Mohamed Ibn Chambas, it was clear that parties on both sides had taken entrenched positions, with no signed agreement to move the electoral process forward. The dialogue was subsequently put on hold.

Informal consultations, however, continued among Guineans, with isolated interventions from the observers. Against this backdrop, the ECOWAS Commission, acting on the directive of the ECOWAS Authority, dispatched a high-level mission to Guinea from 20 to 24 July 2015, among others to hold consultations with the government, opposition leaders and other stakeholders in the Guinean electoral process with a view to encouraging them to resume the dialogue. The dialogue subsequently resumed and on 20 August 2015, both the government and opposition signed an agreement paving the way for the electoral process to proceed with presidential elections, slated for 11 October 2015; local elections planned for the first quarter of 2016; the recomposition of the special delegations; and the appointment of two representatives of the opposition into the CENI.

Presidential elections were held on 11 October 2015 and Condé was re-elected. With elections over, the commitment to continuing with the political dialogue process and the implementation of the August 2015 agreement soon waned. However, in August 2016, Conakry, the country’s capital city, was caught up in violent protests by supporters of several opposition parties over alleged government corruption.27 With growing grievances against the government by segments of the population, the prime minister and head of government, Mamady Youla – having constitutional responsibilities for promoting social dialogue and being the guarantor for the implementation of agreements entered into with social partners and political parties – took the initiative to revive the Inter-Guinean Political Dialogue. Consequently, on 1 September 2016, 11 months after being re-elected as president, Condé and Diallo, the leader of the opposition, met for the first time for talks over the “political, economic and social situation” of the country.28 Both leaders tried to iron out their differences and agreed to have regular meetings to exchange views on how to move the country forward.29 On 22 September 2016, under the chairmanship of the minister of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, the Inter-Guinean Political Dialogue was resumed. On 12 October 2016, an agreement was signed by the representatives of the majority party, the opposition party and the government, with representatives of the international community and civil society signing as observers to the agreement.30 Among other elements, the signed agreement touched on the auditing of the voter register; the postponement of communal elections; the amendment by the National Assembly of Act 016 on the CENI’s composition, organisation and operation for better management of elections; steps towards the establishment of the high court of justice; measures to release people arrested and convicted during political demonstrations, in accordance with the spirit of the dialogue; and compensation for victims of violent demonstrations during the 2013 legislative elections.

A follow-up committee, tasked with implementation of the agreement, was established as a component of the agreement itself. The committee, chaired by the minister of Territorial Administration and Decentralisation or his representative, is composed of three representatives of the majority party, three representatives of the opposition party and a magistrate of the judiciary. Representatives of civil society and the international community (ECOWAS, OIF, UN, EU and the embassies of the United States and France) participate in the committee as observers. The agreement is in effect until after the 2018 legislative elections. The committee, which has been meeting regularly, held its 13th session on 24 July 2017. The president promulgated a new electoral code on 27 July 2017, after its initial review by the National Assembly and the Constitutional Court.

Conclusion

It is important to note that political dialogue processes should be nationally owned and driven, despite being assisted or advocated by the international community. However, as noted in the United States Institute of Peace (USIP’s) 2015 Peacebrief,31 while national ownership of a national dialogue process is fundamental, there are critical points at which the international community can provide important assistance – such as in helping to negotiate the initial agreement that establishes a national dialogue; making public statements in support of national dialogue processes; advocating for an inclusive and participatory process; and commitment to the dialogue process by national actors and stakeholders. Equally important is that the international community and the regional and subregional organisations can also play a role – at least as observers of the dialogue process and follow-up on the implementation of agreements reached – while ensuring that the main responsibility and decision-making remains in the hands of national actors. The experiences of ECOWAS in supporting national political dialogue processes in the region attests to these guiding principles on how the international community can support national political dialogue processes. While regional and subregional organisations can assist in facilitating political dialogues to broker political deadlocks, national leaders and stakeholders must move beyond such “temporary” mediated brokered peace to initiate wider and deeper national dialogue processes, aimed at consolidating and sustaining the peace gained during periods of deep political crisis and political transitions.

Endnotes

- See Article 58 of the 1993 ECOWAS Revised Treaty. ECOWAS Commission (1993) The Revised Treaty of ECOWAS. Abuja.

- The author prepared this paper as part of self-reflections in the course of the Third Conference on National Dialogue, organised by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland and an International Non-governmental Organisation Consortium, 5–6 April 2017, in Helsinki, Finland, where he served as a panellist on the session on Regional Organizations’ Support to National Dialogue Processes.

- The Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC) (2015) Creating Spaces for Dialogue: A Role for Civil Society. Dialogue and Mediation Series, Issue No. 1. The Hague: GPPAC, p. 8.

- West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP) (2012) Dialogue and Mediation: A Practitioner’s Guide. Accra: WANEP, p. 5.

- Pruitt, Bettye and Thomas, Philip (2007) Democratic Dialogue: A Handbook for Practitioners. Stockholm: International IDEA, p. 9.

- WANEP (2012) op. cit., p. 2.

- Folke Bernadotte Academy (2006) Preventing Violent Conflict through Dialogue and Leadership. Seminar Report, Conflict Prevention in Practice Project. Stockholm, p. 3.

- United Nations Development Programme (2014) Guidance note. In UNDP Supporting Insider Mediation: Strengthening Resilience to Conflict and Turbulence. New York: UNDP, p. 10.

- ‘The Role of Political Dialogue in Peacebuilding and Statebuilding: An Interpretation of Current Experiences’. International Political Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding, May 2011, p. 2. Available at: <https://www.pbsbdialogue.org/media/filer_public/bd/c8/bdc8e1a2-65b0-4305-94d8-20d02d05323e/the_role_of_political_dialogue_in_peacebuilding_and_statebuilding>.

- WANEP (2012) op. cit., p. 6.

- The Role of Political Dialogue in Peacebuilding and Statebuilding’, op. cit., p. 2.

- Berghof Foundation (2017) National Dialogue Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners. Berlin: Berghof Foundation, p. 21.

- Giessmann, Hans J. (2016) Embedded Peace. Infrastructures for Peace: Approaches and Lessons Learned. New York: UNDP, p. 35.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- International IDEA (2007) Democratic Dialogue: A Handbook for Practitioners. Stockholm, p. 22.

- Ibid.

- For a detailed analysis of this phase in the history of Guinea and ECOWAS mediation efforts, see Yabi, G.O. (2010) The Role of the ECOWAS in Managing Political Crisis and Conflict: The Cases of Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. Abuja: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- ECOWAS Commission (2008) Communique of the Thirty-fifth Ordinary Session of the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government, held in Abuja, Nigeria, 19 December 2008, p. 9.

- ECOWAS Commission (2009) Communique of the Extraordinary Summit of the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government, held in Abuja, Nigeria, 17 October 2009.

- In the view of the opposition, the CENI should have organised local elections before presidential elections, in accordance with the terms of the 3 July 2013 political agreements. The opposition argued that the president dictated the order of elections to the CENI, to enable the special delegates appointed by the government to perpetrate electoral fraud that would facilitate his re-election. On the part of the government and majority party, the political agreement of 3 July 2013, which the opposition referred to, did not address local elections but rather that of legislative elections. They argued that local elections were the subject of an addendum to the agreement and were only signed by the majority and opposition facilitators, and the international facilitator. It was not binding on the government.

- ECOWAS Commission (2015) Communique of the Forty-seventh Ordinary Session of the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government, held in Accra, Ghana, 19 May 2015.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Giessmann, Hans J. (2016) op. cit., p. 35.

- France-Presse, Agence (2016) ‘Guinea Protests against President Conde leaves One Dead –Reports’, The Guardian, 16 August, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/17/guinea-protest-against-president-conde-leaves-one-dead-reports> [Accessed 3 August 2017].

- AFP (2016) ‘Guinea President, Opposition Meet after Anti-govt Protests’, The Daily Mail, 2 September, Available at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3770279/Guinea-president-opposition-meet-anti-govt-protests.html> [Accessed 3 August 2017].

- Ibid.

- The international partners that followed up on the dialogue process and signed as observers were the UN systems coordinator in Guinea, International Organization of the Francophonie, ECOWAS, the EU delegation in Guinea, the US ambassador, the French ambassador and representatives of civil society.

- United States Institute of Peace (USIP) (2015) ‘National Dialogues: A Tool for Conflict Transformation?’ Peacebrief, 194, p. 4, Available at: <www.usip.org>.