Introduction

Strengthening and deepening engagement with communities in United Nations (UN) peace operations has emerged as a key priority among high-level reviews of the UN system. The report of the High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO), the report of the Advisory Group of Experts (AGE) for the Review of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture, the Global Study on the Implementation of Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, as well as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, have all emphasised the need to develop bottom-up, people-centred approaches. Across the board, there is a renewed commitment to support constructive state-society relations through inclusive, nationally and locally owned, broad-based, consultative processes.

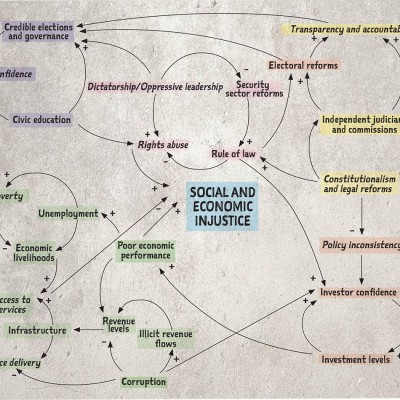

This consensus has come to the fore amidst growing criticisms that the UN remains too state-centric, that it applies predefined peacebuilding templates to diverse contexts and that it increasingly leans on military solutions over political ones. Existing practices often alienate and marginalise the local people whom missions are mandated to serve, and risk “perpetuating exclusion”.1 The renewed resolve to “put people first” is a welcome commitment on the part of the UN, but as a policy commitment, it represents nothing new. What the review processes revealed is that the UN is still not doing enough to ensure local people play an active role in deciding the roadmap to peace. This article highlights the opportunities, challenges and trade-offs peacekeepers have to face when deciding when, who and how to engage with people effectively at the field level. It argues that by integrating bottom-up and people-centric approaches as a core strategy in peace operations, UN practices can be more sensitive and responsive to local people. This will be more realistic if existing practices are incorporated into a coherent strategy, and if communities are involved systematically in decision-making.

A Renewed Resolve to Serve and Protect Local People?

In 2015, the HIPPO report argued that the UN should develop better strategies for community engagement at all stages of the mission cycle, to improve mandate implementation and to ensure that the mission is always responding to local demands.2 The report went on to state that “countries emerging from conflict are not blank pages and their people are not ‘projects’. They are the main agents of peace.”3 The peacebuilding report, criticising the tendency to favour capitals and elites, calls for “inclusive national ownership” and ensuring the participation of broad sectors of society including community groups, women, youth, labour organisations, political parties, the private sector, civil society and marginalised or under-represented groups.4 Both reports call for broadening engagement, particularly to enhance the role played by women and youth in new, challenging domains such as addressing radicalisation and violent extremism. The Global Study also underlined the empirical links between women’s participation and the stability and sustainability of peace, calling for the enhanced role of women in decision-making in all areas of peace operations.5

What is Community Engagement?

Engaging communities and using people-centred approaches have been the backbone of both the development and humanitarian fields for decades. The advent of “participatory approaches” in the 1970s and, later, “people-centred” development in the 1980s emerged as responses to top-down externally led interventions, to empower communities as agents in the design of projects and programmes. Both the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) have released practitioner guidance on “community-based approaches”.6

While “community engagement” has not yet been well defined in the realm of UN peace operations, the Department of Peacekeeping is developing a set of guidelines for mission staff. This is currently in the form of a draft practice note on community engagement. Echoing the HIPPO report, it argues that communities should play an active role in decision-making, implementation, assessment and monitoring, and maps out the potential role of communities at each of these junctures. Three core engagement goals are stated.7 The first is communication, which ensures communities receive the information necessary for self-organisation. The second is consultation, which enables the sharing of perspectives, grievances, needs and priorities that become key data for decision-making and evaluation. The third is empowerment, which facilitates local people’s direct involvement in decision-making. These principles are already practised in most peacekeeping missions, and are usually applied as parallel, complementary processes. For instance, strategies to tackle intercommunal violence often involve communication through media campaigns to assuage hate speech and rumours; consultation with communities take place to monitor volatile situations; and community leaders are often empowered as conflict mediators.8

Community Engagement in UN Peace Operations: Tools, Policies and Best Practices

Over the years, the UN has developed a range of tools, policies and best practices to ensure peacekeeping missions are better equipped to engage with local people. These approaches are still not systematic, and lack a consistent methodology.

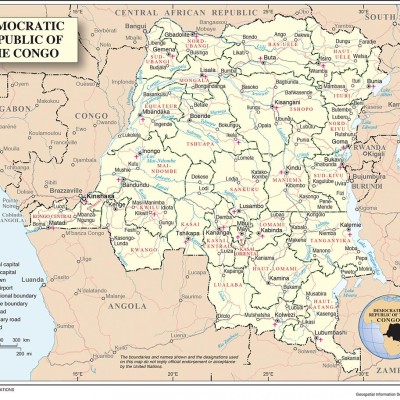

Gathering Local Data and Information Management

Evidence shows that peacekeeping forces which valorise local sources of knowledge consistently develop better relations with local people, and are thus able to carry out their mandates more effectively.9 Civil Affairs teams gather vast and rich data on local conflict dynamics and protection threats on a daily basis. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Must-Should-Could Protection of Civilians Matrix (MSC) enables actors in the field to jointly define and rank protection threats, as well as defining what action should be taken – such as setting up a patrol in a particular village. A key challenge in many missions, however, is that information is not always routinely or effectively funnelled into mission-wide analyses. Local Civil Affairs teams in the UN Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) have overcome this by using the Joint Mission Analysis Cell’s (JMAC) weekly predictive risk assessment matrix, which synthesises risks against civilians in a geographic table, as a modality for organising its information into concise briefs, often on a province-by-province basis.10 This contributes to the overall mission-wide awareness of protection threats.11 Another challenge is that views from the field do not always travel upstream, and fail to reach senior leadership. Experts have thus advocated for both formal processes, such as increased community participation in formal planning and assessment processes, as well as more informal processes, such as systematising town hall visits by senior leadership.12

Perception Surveys

Capturing local perceptions is becoming an important best practice for peacekeeping missions, and helps the mission understand how its interventions impact people on the ground. Since 2005, UN peacekeeping operations have commissioned perception surveys in the DRC, Haiti, Lebanon, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Somalia. Perceptions of local people provide useful insight on local drivers of violence against civilians, which is important when designing protection strategies.13 Public opinion surveys are also useful means of tracking priorities and needs of communities, which change over time. For example, in the DRC, perception surveys revealed that people prioritised softer peacebuilding initiatives (such as local conflict resolution and reconciliation) over infrastructure development, while in Sudan, surveys have resulted in a shift in programming to be significantly more community-based, targeting youth in particular to foster stability.

Information and Communications Technology, and Media

Media and information and communications technology (ICT) are increasingly used as resources for facilitating community engagement from the bottom up, ensuring that key messages reach remote populations. Radio is often the most far-reaching and commonly used means of spreading information in current peace operations. In Mali, radio was an important communication tool used to raise awareness on the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali’s (MINUSMA) mandate, and to inform the public about the purpose of its operations.14 Similarly, Radio Miraya in UNMISS has been an effective channel for explaining the government’s official priorities to remote communities. Still, challenges remain when communities do not have access to such media outlets and when missions reside in large countries with limited infrastructure. ICT can also be used to report back to the mission. For example, text messaging as an early warning tool has been piloted in the DRC to alert the mission about protection threats, and in Kenya to track electoral violence.15 The UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) has distributed mobile phones to women, enabling them to report incidents of conflict-related sexual violence.

Who to Engage?

Both the HIPPO and AGE reports advocate for broader engagement, moving beyond elites to include women, youth and marginalised groups in particular. But choosing who to engage with deserves careful consideration by mission staff. Perceptions by local people that the mission is engaging with one group more than another could lead to accusations of partiality. Common practice has seen the engagement of elites, residing in capital cities, who do not always represent the views of communities living remotely. Exclusion is one of the main reasons why people take up arms and resort to violence.16 Research shows that inclusive processes substantially increase the chances of achieving sustainable peace – particularly when stakeholders are able to make quality contributions that influence decision-making and implementation.17 Locating legitimate representatives can be challenging, as local actors, too, come with their own agendas. Stakeholder mapping – a common practice carried out by Civil Affairs – can be key to deciphering whether leaders have a strong constituent base, which is a critical indicator of legitimacy.

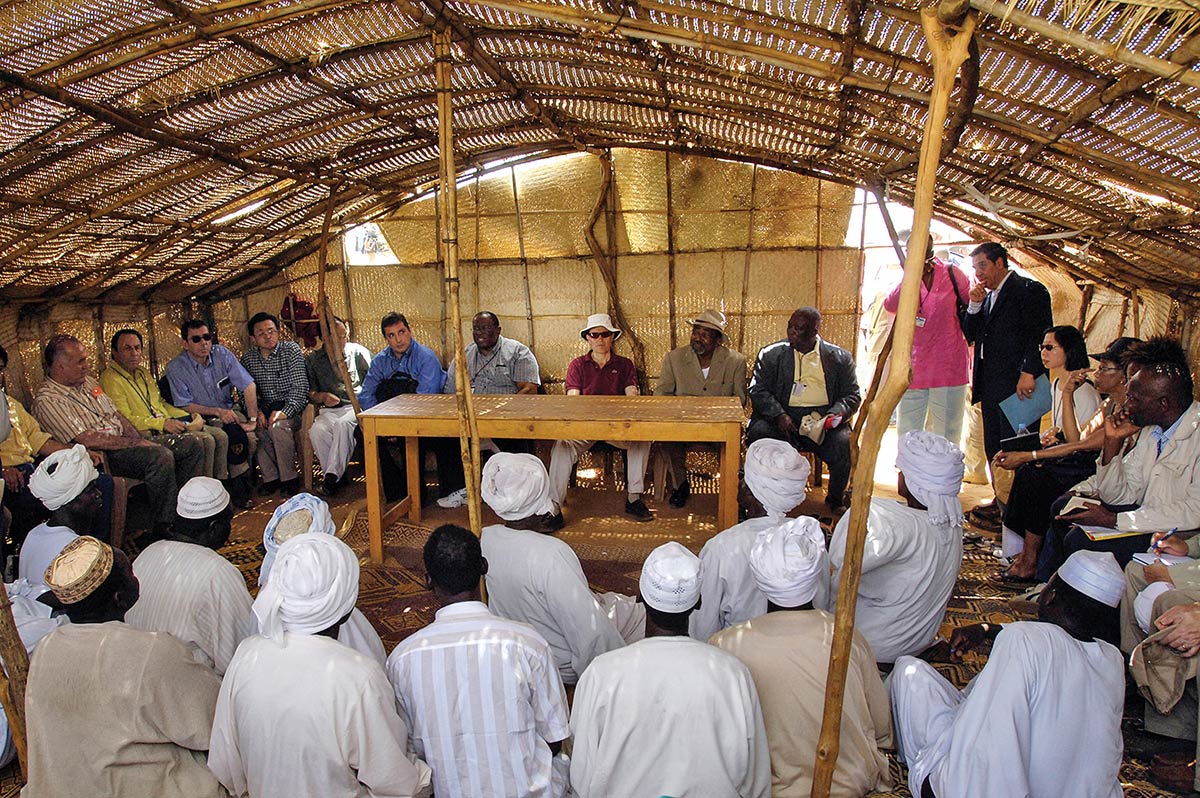

There are, of course, trade-offs between opting for wide versus deep engagement. Small processes may be easily steered and deliver quicker results, while large consultations offer the means for broader representation and participation, but are time-consuming and resource-heavy, as in the case of the Bangui Forum on National Reconciliation in Central African Republic (CAR). The UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) facilitated widespread local consultations prior to the forum to ensure community representatives’ participation. The event gathered over 600 leaders from diverse sections of CAR’s society – including the transitional government, political parties, the main armed groups (the Séléka and anti-Balaka), the private sector, civil society, traditional chiefs and religious groups, women, diaspora and refugee populations – to arrive at a collective vision for the future. However, the consultations were not backed by action plans and failed to generate a concrete roadmap. The donor community was largely absent from the process, which raised scepticism about the feasibility of implementing these recommendations – signalling the importance of also engaging key, strategic players from the top down.

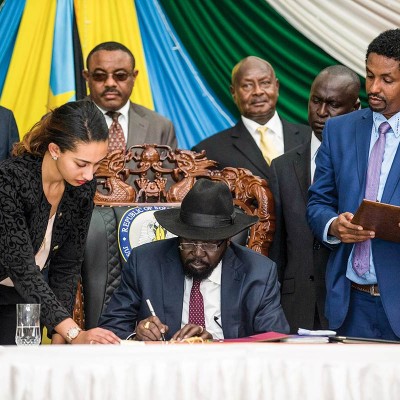

Using local intermediaries that connect the mission with communities is now becoming an institutionalised practice in UN peace operations. UNMISS used county support bases (CSBs) in South Sudan as remote offices for mission staff in rural, remote areas to expand the mission’s presence. In 2010, community liaison assistants (CLAs) were introduced by the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC’s (MONUSCO) Civil Affairs to bridge the gap between local communities and the mission. These local staff, trained and hired by the UN, are deployed with peacekeepers to build networks with local authorities, civil societies and communities in remote parts of the country. As of 2015, there were over 200 CLAs in about 70 military bases throughout the eastern DRC.18 They support increased engagement by offering translation services, establishing connections and informing local people about the mission’s mandate, and are a vital resource for gathering information on local conflict dynamics. This best practice has been commended for facilitating confidence-building between peacekeepers and local communities, and has been replicated in other missions including CAR and Sudan.

The question of whether to engage non-state actors is becoming particularly challenging in conflicts that fall under the purview of the “global war on terror”. Theoretically, the UN has the potential to act as a neutral and impartial arbiter, with the legitimacy to engage all parties to a conflict. However, in the post 9/11 context, labels used to categorise armed non-state actors (ANSA) as “terrorists” and “Islamic violent extremists” place boundaries on with whom missions can publicly engage. This has been a challenge for mission staff in MINUSMA. Being perceived to be soft on “terrorists” will likely result in a backlash from the host state and conflict-affected populations who have been subjected to abuse and occupation. While missions engage in quiet advocacy to encourage ANSA to adhere to international humanitarian law or to stop the recruitment of children, such engagement remains limited and controversial.19

Finally, reconciling engagement with the host state is another challenge for peace operations. Missions face a number of restrictions from the state in places such as Darfur, South Sudan and Burundi, which is a challenge to mandate implementation. When missions take on issues that fall into the domain of “politics”, they are often accused of meddling with sovereign affairs. For example, the UN–African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) is restricted in its ability to engage with communities because of access restrictions. The state prevents the mission from reaching communities that have been affected by state-led counterinsurgency campaigns and which are in grave need of humanitarian assistance, fearing international scrutiny. Negotiating the parameters of consent is a delicate exercise. Pushing these limits too far could result in the removal of the mission – which could jeopardise the well-being of the communities the mission does have access to.

How to Engage Local Communities Effectively

What role should the UN play in community engagement? There is broad consensus among field staff that the UN should play a facilitating or “accompaniment” role, which involves enabling more and doing less.20 This is critical to allow space for self-organisation – an important tenet for building resilience,21 local ownership and sustainability. This involves enhancing existing structures, such as traditional justice mechanisms or local conflict resolution bodies. This resonates with the “process over content” argument, which suggests that the UN should avoid influencing the outcome of engagement activities.22 Such back-seat facilitation could involve providing technical capacity and providing logistical support – for example, by transporting key figures to dialogues or meetings, or using air assets to reach cut-off regions.

Engaging local people can also happen at a micro scale – in the daily practices of peacekeepers. As a first step, this would involve increasing interaction with local staff by sharing office spaces and resources to integrate local colleagues, as ways to increase “socialisation”.23 However, community engagement must also be strategic, with sufficient buy-in from top-level leadership. Field staff with the best intentions regularly face bureaucratic and programmatic challenges. Incentivising senior leadership to shift their thinking towards communities will be key for an effective community engagement strategy. This could be achieved through incorporating benchmarks in the mission strategy and tying community engagement to the mission mandate, to hold decision-makers accountable. These commitments must also be backed by financial and human resources, which should be reflected in the mission budget.

UN missions engage local communities through a range of modalities. Examples include organising workshops and meetings with government officials, tribal leaders or other authority figures for conflict resolution, or facilitating town hall meetings. Of course, these types of meetings should be backed up with action to avoid “dialogue fatigue”. Consultations create expectations, and if these are not met it can lead to frustration from local people. Practitioners have also highlighted that ensuring two-way information streams between the mission and local people is fundamental to building trust and confidence. Local people often complain that mission staff only visit to collect information, but rarely provide answers to their questions in return. Improved mechanisms for follow-up, feedback and complaint channels should be developed.

The most comprehensive, systematic attempt to integrate a bottom-up strategy that involved local people in decision-making was implemented in the DRC under the purview of the International Security and Stabilisation Support Strategy (I4S) – a donor-led stabilisation initiative that seeks to unite MONUSCO, UN agencies, local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and donors behind a common strategy for stability. Between 2009 and 2012, US$367 million was spent on stabilisation activities such as infrastructure projects, and extending state authority through the training and deployment of state officials and the army. This strategy was criticised for being elite-focused, top-down, technical and far removed from the local dynamics of conflict. Most significantly, it did not lead to a reduction in violence.24 These failures precipitated a drastic revision of the I4S, led by the Stabilisation Support Unit (SSU) in MONUSCO. In the revised strategy, one of the core pillars is “democratic dialogue”, which gathers representatives from all sections of the community – including armed groups – in an effort to identify root causes and solutions to conflict.25 Local peacebuilding NGOs function as implementing partners in the roll-out of projects. The downside of such a methodological approach, however, is that it is time-consuming, resource-heavy and project-heavy, which means replicability to other missions that are already underfunded could be challenging.

Operating in a Securitised Landscape

As peace operations are increasingly being deployed in areas where there is no peace to keep, security constraints will hinder systematic community engagement in the absence of a peace agreement. In Mali, MINUSMA’s Stabilization and Recovery Section (S&R) designed regional stabilisation strategies through a bottom-up consultative process, but was limited in its engagement with local actors because of security threats – civilian staff had to be accompanied by military contingents, and the most remote regions under armed group occupation could not be reached at all. The mission had to rely on the All Source Information Fusion Unit (ASIFU) – the first intelligence unit deployed in a UN mission – to conduct its conflict analysis, which served as a basis for developing programme priorities. Another important issue to consider is the risk borne by communities that engage with mission staff. In Mali, one of the key causes for armed groups attacks on civilians is retaliation and reprisals for suspected collusion with “foreign” forces.26 In such cases, it is vital that the mission conducts comprehensive risk assessments to ensure that individuals or communities are not jeopardised by the mission’s actions.

Conclusion

Community engagement strategies have the potential to make peace operations more responsive to local dynamics. Yet, as this article highlights, there are a number of dilemmas that arise when considering community engagement strategies in practice. The UN already has a range of tools and policies at its disposal, but for community engagement to be more systematic, these need to be harnessed into a coherent strategy. Choosing who to engage with also requires careful stakeholder mapping and identifying the risks associated with excluding certain groups. Not all contexts will be conducive to introducing a system-wide community engagement strategy, due to resource and security constraints. Moving forward, the UN will not only have to develop concrete guidance and toolkits for peacekeepers, but will also have to foster senior leadership buy-in to consider how mission structures and budgets can be reformed to ensure that the commitment to engage communities moves from rhetoric to reality.

Endnotes

- United Nations (2015) The Challenge of Sustaining Peace: Report of the Advisory Group of Experts for the 2015 Review of the United Nations Peacebuilding Architecture. New York: United Nations, p. 21.

- Ramos-Horta, José (2015) Report of the High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations on Uniting our Strengths for Peace: Politics, Partnership and People. New York: United Nations.

- Ibid., p. 78.

- United Nations (2015) op. cit., pp. 21–22.

- UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN WOMEN) (2015) Preventing Conflict Transforming Justice Securing the Peace: A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. New York: United Nations.

- See, for example, UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) (2008) A Community-based Approach in UNHCR Operations. New York: United Nations. pp. 1–13; and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (2015) ‘OCHA Message: What is Community Engagement?’, p. 1, Available at: <https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OchaOnMessage_CommunityEngagement_Nov2015.pdf> [Accessed 10 August 2016].

- This draft practice note is a constantly evolving document and has not yet been published. Therefore, these “engagement goals” should be interpreted flexibly.

- Policy & Best Practices Service Department of Peacekeeping/Department of Field Support (2016) Draft Practice Note: Community Engagement. New York: United Nations, pp. 9–10.

- Williams, Paul (2013) Protection, Resilience and Empowerment. Political Studies Association, 33(4), pp. 287–298, DOI: 10.1111/1467-9256.12014.

- Brockmeier, Sarah and Rotmann, Philipp (2016) ‘Civil Affairs and Local Conflict Management in Peace Operations: Practical Challenges and Tools for the Field’, Global Public Policy Institute Policy Paper, p. 32, Available at: <www.gppi.net/civilaffairstoolkit> [Accessed 9 August 2016].

- Ibid.

- Policy & Best Practices Service Department of Peacekeeping/Department of Field Support (2016) op. cit., pp. 19–20.

- Giffens, Alison (2013) ‘Community Perceptions as a Priority in Protection and Peacekeeping’, Issue Brief 2. Civilians in Conflict. Stimson. Available at: <https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/171557/CIC-No2.pdf>. [Accessed 8 August 2016]

- Anonymous (2016) Interview with the author on 24 June. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Scaturro, Giorgia (n.d.) ‘Tech for Peace: Facts and figures’, SciDev.Net, Available at: <http://www.scidev.net/index.cfm?originalUrl=global/conflict/feature/tech-for-peace-facts-and-figures.html> [Accessed 10 August 2016].

- Paffenholz, Thania (2015) Inclusivity in Peace Processes: Briefing Paper for the UN High-level Review Panel. Tokyo: United Nations University Centre for Policy Research.

- Ibid.

- MONUSCO Civil Affairs (2014) CLA Best Practice Review 2014. New York: United Nations.

- Von Einsiedel, Sebastian (2015) ‘Non-military Protection of Civilians in UN Peace Operations: Experiences and Lessons’, p. 7, Available at: <http://i.unu.edu/media/cpr.unu.edu/attachment/1182/OC_03-Non-Military-PoC-in-UN-Peace-Ops.pdf> [Accessed 10 August 2016].

- Views gathered from the Community Engagement in UN Peace Operations Workshop, hosted by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs and United Nations Policy and Best Practices Service, New York, 2–4 February 2016.

- De Coning, Cedric (2016) From Peacebuilding to Sustaining Peace: Implications of Complexity for Resilience and Sustainability. Resilience, DOI:10.1080/21693293.2016.1153773.

- De Coning, Cedric et al (2015) Towards More People-centric Peace Operations: From ‘Extension of State Authority’ to ‘Strengthening Inclusive State-Society Relations’. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 4(1): 49, pp. 1–13, DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/sta.gl>.

- Autesserre, Séverine (2015) ‘A Message from Peaceland: Change the Way UN Peace Operations Interact with Local Actors’, global peace operations review, Available at: <http://peaceoperationsreview.org/interviews/a-message-from-peaceland-change-the-way-un-peace-operations-interact-with-local-actors/> [Accessed 9 August 2016].

- De Vries, Hugo (2015) Going Around in Circles: The Challenges of Peacekeeping and Stabilization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. CRU report. The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael.

- Solhjell, Randi and Rosland, Madel G. (2016) New Strategies for Old Conflicts. Policy brief, Thematic Paper Series. Oslo: NORDEM.

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) (2015) ACLED Country Report on Mali. ACLED.