Introduction

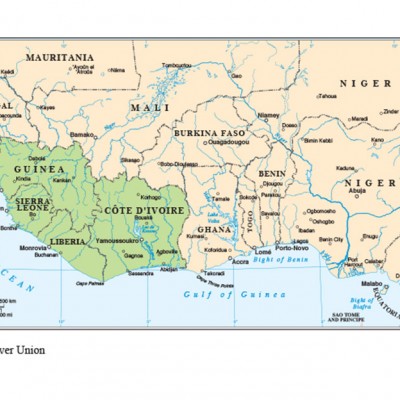

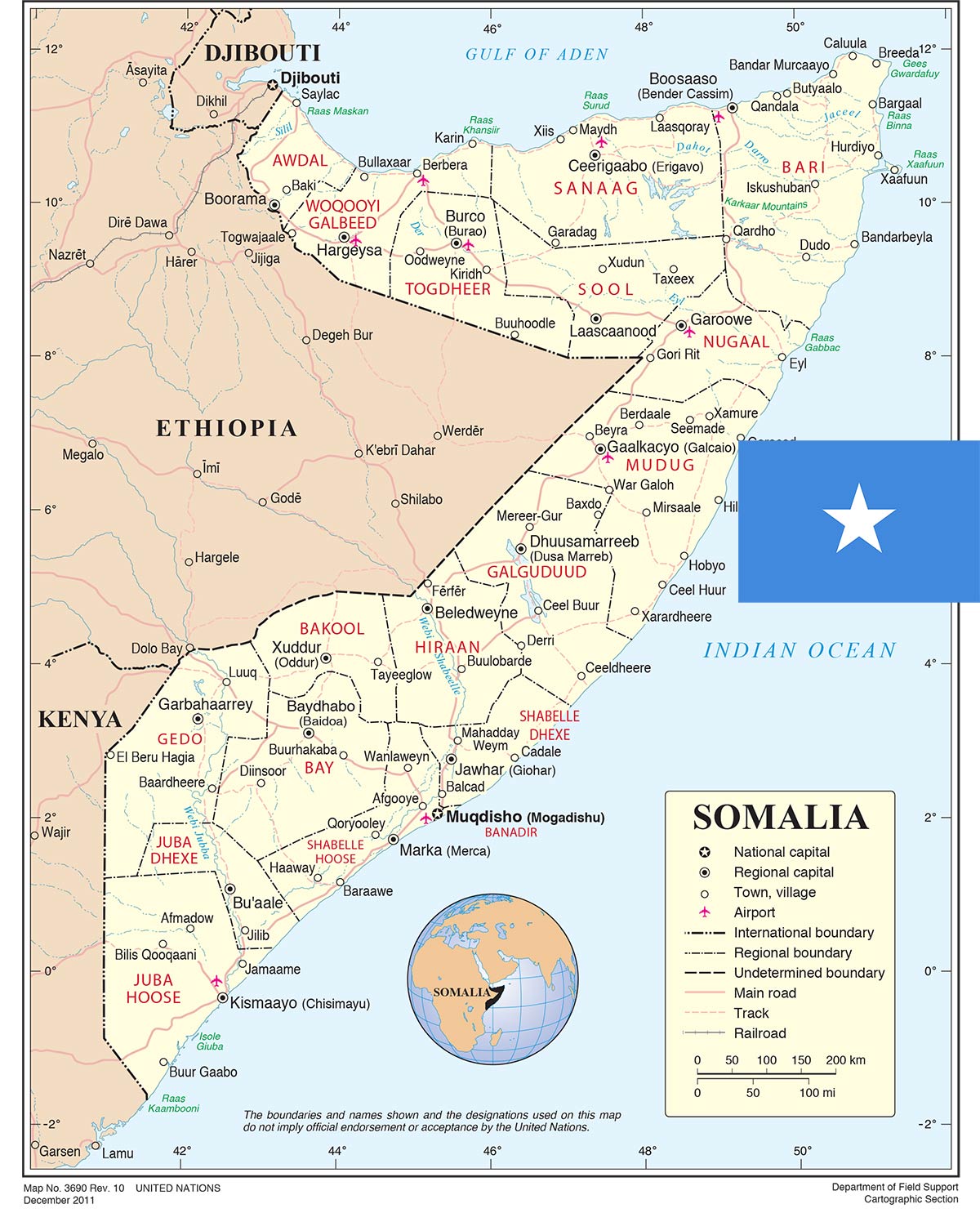

Somalia has experienced state failure, collapse and disintegration since the fall of the Mohamed Siad Barre military regime in 1991. Since then, the country has been the subject of numerous peace processes aimed at the creation of a central government, without any success. This absence of a central government means that Somalia has failed to meet the basic functions associated with the Westphalian state system1 of providing common goods to its population, developing and promulgating laws of the country, and providing security for its population through the use of legitimate force.2 The failure, collapse and eventual disintegration of the Somali state since 1991 facilitated the emergence of civil militia groups, often aligned to various political clan groupings. These militia groups operate under the pretext of providing security to their clansmen and, in the process, have created what scholars describe as a security dilemma, where clans arm themselves in anticipation of attacks by rival clans.

The clan political differences are used as instruments of conflict perpetuation by civil militia leaders in their quest to plunder what remains of Somalia’s resources. This article focuses on the instrumentalist school of thought, and concludes that clan differences are used by civil militia groups as instruments of conflict perpetuation in the Somali conflict. However, given the Somali clan system, arguments from the primordialist school of thought3 cannot be ignored in analysing the situation in the country. Similarly, the suggestion of the Wahhabism4 influence within civil militia groups is not based on empirical evidence, but rather on profiling the Somali state as a breeding ground for religious-related terrorism.

Somali State Failure, Collapse and Disintegration

The terms “collapsed state” and “failed state” signify the consequences of a process of decay at the nation-state level, where the capacity of those nation-states to perform positively for their citizens has atrophied.5 The phenomenon of state collapse is generally understood as the breakdown or disintegration of centralised political institutions and the system of authority that underlies them, and the unravelling of complex relationships between the state and society. In the case of extreme state collapse, the very order of society disintegrates.6 First, like many post-colonial states, Somalia was fundamentally weak since its creation by British and Italian colonialists. Second, the creation of the post-independence Somali state was hampered by poor leadership, which lacked the capacity to define national priorities conducive to consolidating short-term achievements related to the granting of political independence by colonial powers. In elucidating the role of leadership in state failure, William Reno observes that political leadership which lacks capable administration finds markets to be useful for controlling and disciplining rivals and their supporters, while intervening in markets enables rulers to accumulate wealth directly, which is then converted into political resources they can distribute at their discretion.7 Reno further observes that a failed state bears the hallmark of a fragmented society divided along ethnic, clan and religious lines. Most importantly, ethnicity is used as a rallying point to mobilise society for war. The early post-independence Somali leadership was caught in this poor leadership syndrome of distributing patronage along divisive clan affiliations that further weakened the state-creation process.

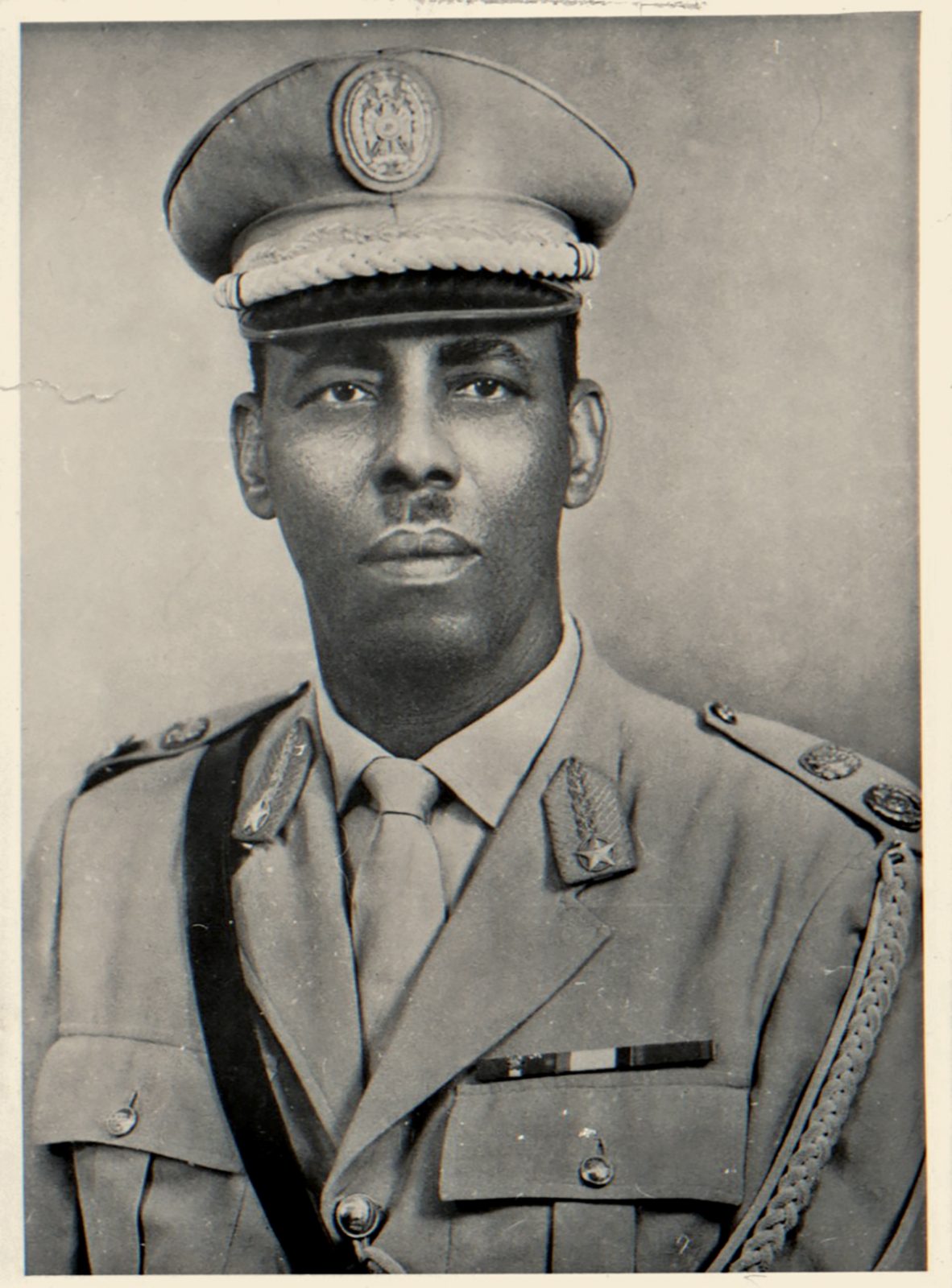

Siad Barre and Civil Militia Groups

The rise of General Siad Barre’s military government in 1969 was a major contributory factor in the process of state failure in Somalia. It was during Barre’s military rule that ethnicity became a factor of political life in Somalia. The Siad Barre military government was commonly referred to as MOD (Marehan, Ogaden and Dulbahunte)8 – which were the main clans that exercised hegemony over other clan families during the military rule. Ioan Lewis observes further that the political exclusion of other clans and a crackdown on the religious establishment became a source of conflict between the regime and those excluded from the mainstream politics, economics and social spheres of the country.9 Although Siad Barre claimed to embrace pan-Somali nationalism, his military regime was dominated by the MOD cabal. Paradoxically, what Siad Barre created in the end was a clan military dictatorship, which was eventually transformed to a clan civil militia group when his regime collapsed in 1991.

The 1977–1978 war between Somalia and Ethiopia over the Ogaden region, and the eventual defeat of Somalia, altered the military balance of forces in the Horn of Africa in favour of the victorious country. Consequently, it was Somalia’s defeat in the Ogaden War that compounded and fast-tracked the process of state collapse. Somalia was, by then, awash with weapons of war, the military regime was not capable of exercising control over the entire country, and clan-affiliated military resistance against the regime increased. The Ogaden War with Ethiopia revealed weaknesses in Siad Barre’s leadership, and his hollow authority.10 The Darod clan of Siad Barre became fragmented as the attempted coup by its Majerten subclan members was foiled. With the consequence of clan political power waning, in a situation characterised by clan contestation in the political arena and changes demanded in the military balance of power, the regime was further weakened. The triple burden of Somalia’s defeat in the Ogaden War with Ethiopia and the accompanying national humiliation, an economy in decline, and the absence of superpower patronage was instrumental in the process of state failure in Somalia.11 The Somali political battle then viciously turned inward, with implications of state failure, collapse and disintegration in 1991. Siad Barre’s Ogaden debacle led to the search for a clan scapegoat, with the result that clan cleavages were made prominent. It was this inward turn towards clan rivalry that created the clan security dilemma, with serious consequences on the civil war that still ravages Somalia and the emergence of clan-based civil militia groups. The militia groups then assumed the responsibility of protecting their specific clans’ interests, while clan political structures were providing civil militia leaders with new militia recruits.

In 1989, the Hawiye clan-based United Somali Congress created a military force under the leadership of General Mohamed Farah Aideed, who hailed from the Habr Gedir Saad subclan of the Hawiye. Siad Barre allegedly responded to the military situation by urging the Darod clan in Mogadishu to kill Hawiye clan members.12 The ensuing interclan violence threatened Siad Barre’s position and, in desperation, he turned his heavy war machinery on the Hawiye quarter of Mogadishu. Similar military rebellions – and repression – were occurring in other parts of the country. Siad Barre turned Mogadishu into another military front, and overstretched his military capability to contain the military rebellion that was already spiralling out of control across the country. The northern part of Somalia had some of the strongest military resistance to the regime – and Siad Barre responded with further attacks against the civilian population in Hargeisa and other major cities of Somaliland. The port city of Kismayo was equally engulfed in a clan-based conflict that likely had its roots in a pastoral conflict between the Marehan and Ogadeni subclan pastoralists over resources in the Juba region. By then, the conflict in the country had assumed distinct clan identity and character, and militia leaders were consolidating their stranglehold on what remained of the collapsing Somali state.

The Siad Barre-era clan conflict was about state capture, even though the instruments of the state were under serious threat and were gradually collapsing under the control of Siad Barre’s military regime. On 27 January 1991, a popular uprising and general breakdown in security drove Siad Barre from his bunker in the ruins of Mogadishu into a tank, which eventually took him into exile. He left behind a country in ruins without a central government, and it marked a new chapter in the Somali conflict. There was no strong government capable of filling the vacuum; instead, there were numerous fragmented civil militia groups, organised along clan patronage and lineage. These civil militia groups turned against each other once Siad Barre was defeated. Lack of agreement by the civil militia leaders on the formation of a government – at times encouraged by external influences – were critical in the further collapse and disintegration of the Somali state. The departure of Siad Barre created a void in which there was no single entity with legitimacy to use force and to develop and make laws in Somalia. Similarly, there was no single force to provide security; people were left to fend for themselves, and the country disintegrated into anarchy. Since the disintegration of the Somali state, the international community has attempted to create a central government – at times, to the detriment of peacemaking processes. The availability of large numbers of small arms in Somalia was pivotal in the evolution of civil militia groups, and lies at the source of the current conflict.

Civil Militia Phenomenon

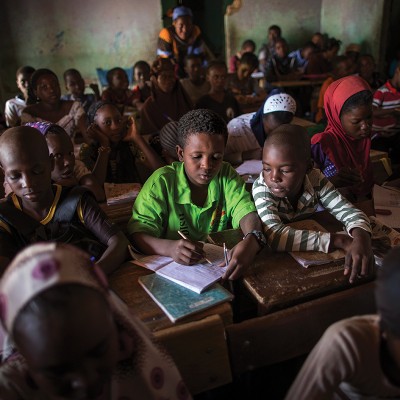

While the international community was focused on conferences and gatherings to encourage the creation of state institutions as a means of transforming the Somali conflict, a new civil militia phenomenon was emerging and gaining traction in Somalia: third-generation civil militia groups. This new generation of civil militia groups operate only in conditions of state disintegration, with no state instruments – not even in their weakest forms. The term “militia” has a Latin origin, meaning “soldiery” from the word miles meaning “soldier”, and has evolved over time to mean “auxiliary or reserve military force”. A popular definition of civil militia presents the view that it is men between the ages of 16 and 60 years who perform occasional mandatory military service to protect their country, colony or state. But it also refers to bands of locals who arm themselves on short notice for their own defence.13

Conceptually, the history of militia groups can be placed within the framework of the theory of the social contract, which is the foundation of the Westphalian state system. Thomas Hobbes and Hugo Grotius believed that insecurity in the state of nature compelled man to seek security in social organisations, where individuals give up their partial freedom for secured freedom provided by the state.14

The original ideas of militia groups have been overtaken by a new breed of militias that operate in situations of failed, collapsed and disintegrated states, such as Somalia. To this end, there is growing evidence that this group of “disruptive militias” are emerging in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, South Sudan, Syria and Central African Republic. Third-generation civil militia groups are often organised along narrow political lines, religious intolerance and ethnicity. Factional militias are the most prominent type of armed group in failed and disintegrated states, and are often formed along clan political structures, where they represent the clan’s political aspirations and defend its territory. The point of departure of third-generation civil militia groups is that they are found where the domestic sovereignty of the state has been decimated. These militia groups have the propensity to balkanise the country among themselves to maximise their benefits in the war economy of failed states.

The emergence of civil militia-controlled areas and the plundering of what has remained of the Somali state effectively means that the state ceased to exist as it was constituted in 1960. Civil militia groups that controlled Somalia were vilified and defined in relation to the United States (US) global war on terror, and the denigration of some civil militia groups as being aligned to Al-Qaeda further compounded the quest to find sustainable peace. The Ethiopian government describes militia groups not aligned to its geostrategic interests in the region as Al-Qaeda-inspired terror groups, and refuses any efforts aimed at bringing such militia groups to the negotiation table. Consequently, the impact of the Somali conflict has spilt over to its neighbouring countries, particularly Kenya and Uganda. These two countries have recently experienced high incidents of terror attacks. Similar to Ethiopia, they have been outspoken in their description of Somali militia groups as being aligned to Al-Qaeda, ostensibly to attract US military support and other economic-related support.

Islam and Civil Militia Groups in Somalia

Religion among Somalis invariably means Islam, of Sunni (a moderate kind of Islam) affiliation, and insofar as Somalis apply Islamic law, they follow the Shafi’ite school. Somalis adopted this religion gradually and of their own volition; it was never imposed on them.15 Somalis are also Sufis in terms of their Islamic faith. Sufism – the mystical view of the Muslim faith that exalts the charismatic powers of its saints – is particularly well adapted to the Somali clan system, in which clan ancestors readily become transposed into Muslim saints.16 These Muslim saints are a fundamental departure from the Salafi and Wahhabi forms of Islam, which are founded on the theology of absolute monotheism (tawhid); they are different to the radical views of Wahhabism-inspired groups like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Sufism is long established and well developed in Somalia,17 and Al-Shabaab18 is inspired by Somalis who believe in the Sufi sect of Islam. While some scholars suggest that Al-Shabaab has its roots in Al-Qaeda, there is yet no empirical evidence to this effect.

Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the founding father of Wahhabism, believed that only Islam adhered to the doctrine of absolute monotheism, setting it apart from every other religion, including Judaism and Christianity. It is on the basis of this strict adherence to monotheism that the Somali’s Sufi beliefs are inevitably a point of conflict with Al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda alliances – as is the case with the Taliban groups in Afghanistan and Pakistan – are founded on the common understanding that Wahhabism is the guiding interpretation of the Islamic faith.

European imperialism served as a catalyst for Islamic revivalism in several parts of the Muslim world: Emir Abdel Kader in Algeria, the Sanusiyya in Libya, the Wahhabis in Saudi Arabia, the Mahdi in the Sudan, and the Sayyid in Somalia.19 This argument seems to be supported by current developments in Somalia where radicalisation correlates with external political intervention, such as the invasion of Somalia by Ethiopia in 2006. This invasion, and eventual defeat of the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) by Ethiopian armed forces, resulted in the creation of the Al-Shabaab resistance group. Lewis suggests that the Al-Qaeda/Al-Shabaab matter became an issue following the 9/11 attacks in the US, and concludes that there is no evidence to support the suggestion that Al-Qaeda has some level of influence within Somali militia groups.20 And as mentioned previously, the continued categorisation of Al-Shabaab as being Al-Qaeda-inspired is without evidence. There appears to be ideological convergence between Al-Qaeda and ISIS, as opposed to a relationship with Al-Shabaab, in Somalia. There is evidence that Al-Shabaab has carried out attacks similar to those of Al-Qaeda and ISIS, but this does not make Al-Shabaab their ally.

Conclusion

The failure, collapse and disintegration of the Somali state has resulted in the balkanisation of the country along clan-militia divides. These divided clan-militia groups lack the capacity to reunite the country and create a central government. The groups are sustained and supported by their clansmen, who depend on them for protection and political support in a situation of anarchy. Similarly, these groups are also dependent on their clansmen for the supply of new militia recruits. The interdependency between militia leaders and clan elders, therefore, has created an intractable situation and a significant challenge to conflict resolution in Somalia. The Somali conflict requires the investigation of new approaches to conflict resolution, particularly in the specific situation where the central government has collapsed and disintegrated and there is no legitimate authority to use violence.

In addition, the emergence of disruptive civil militia groups in countries such as Libya, Syria, Iraq and Yemen is a challenge that the international community and academia need to explore. The emergence of these groups in disintegrated states has challenged the contemporary state system as the source of peace and stability, and this is evident in Syria, Libya and Yemen, where the process of state disintegration is gaining momentum.

The fact that the contemporary system of states is unable to relate to states without a government further compounds the conflict resolution process in collapsed states. Global political dynamics and the war against terror has resulted in the vilification of disputants in conflict areas, particularly in Somalia. And while the simple categorisation of Al-Shabaab as Al-Qaeda-inspired is without much foundation, evidence indicates that disputants have used the Al-Qaeda factor in the Somali conflict to access global funding from war against terror projects in the US. Neighbouring countries have also used the Al-Qaeda fear factor to access economic and military funding from the US and other Western governments. Al-Qaeda’s practice in other cases suggests that it would have required a show of loyalty from its allies – for example, by demanding the destruction of holy sites in Somalia – had there been any ideological convergence with Somali militia groups. Even if Al-Shabaab is not necessarily aligned with Al-Qaeda, the group has adopted similar strategies and tactics to those of Al-Qaeda and ISIS in attacking civilian populations, at times even across the borders of Somalia.

Endnotes

- The Peace of Westphalia refers to the pair of treaties (the Treaty of Münster and the Treaty of Osnabrück) signed in October and May 1648 which ended both the Thirty Years’ War and the Eighty Years’ War. The three main principles of a Westphalian state system are: the sovereignty of states and the fundamental right of political self -determination, (legal) equality between states, and non-intervention of one state in the internal affairs of another state.

- Vinci, Anthony (2009) Armed Groups and the Balance of Power: The International Relations of Terrorists, Warlords and Insurgents. London: Routledge, pp. 11–40.

- Primordialism contends that nations are ancient, natural phenomena. It emphasises the concept of kinship, where members of an ethnic group feel they share characteristics, origins or sometimes even a blood relationship.

- Wahhabism refers to the very conservative and radical side of Islam. Wahhabism represents Salafi piety, that is, its adherence to the original practices of Islam and the movement’s vehement opposition to the Shia branch of Islam.

- Rotberg, Robert (2004) The Failure and Collapse of Nation States: Breakdown, Prevention, and Repair. In Rotberg, Robert (ed.) When States Fail. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 14–20.

- Demetriou, Spyros (2003) Rising from the Ashes? The Difficult (Re)Birth of Georgian State. In Milliken, Jennifer (ed.) State Failure, Collapse and Reconstruction. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 1–45.

- Reno, William (1998) Warlord Politics and African States. Colorado: Lynne Rienner, pp. 21–24.

- Osman, Abdulahi A. (2007) The Somali Internal War and the Role of Inequality, Economic Decline and Access to Weapons. In Osman, Abdulahi A. and Souare, Issaka K. (eds) Somalia at the Crossroads: Challenges and Perspectives on Reconstructing a Failed State. London: Adonis & Abbey Publishers, pp. 83–108; and Lewis, Ioan M. (2002) A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. Athens: Ohio University Press, pp. 226 and 73.

- Lewis, Ioan M. (2002) op. cit., pp. 226 and 73.

- Lyons, Terrence and Samatar, Ahmed I. (1995) Somalia: State Collapse, Multilateral Intervention, and Strategies for Political Reconstruction. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, p. 14.

- Samatar, Ahmed I. (1994) The Curse of Allah: Civic Disembowelment and the Collapse of the State in Somalia. In Samatar, Ahmed I. (ed.) The Somali Challenge: From Catastrophe to Renewal? Boulder: Lynne Rienner, p. 117.

- Bradbury, Mark (1994) The Somali Conflict: Prospects for Peace. Oxfam Working Paper. Oxford: Oxfam, pp. 1–105.

- Yoroms, Gani Joses (2005) Militias as a Social Phenomenon: Towards a Theoretical Construction. In Francis, David J. (ed.) Civil Militia: Africa’s Intractable Security Menace? Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 31–50.

- Ibid.

- Van Notten, Michael (2005) The Law of the Somalis: A Stable Foundation for Economic Development in the Horn of Africa. Asmara: Red Sea Press, pp. 29.

- Lewis, Ioan M. (2002) op. cit., p. 63.

- Lewis, Ioan M. (2010) Making and Breaking States in Africa: The Somali Experience. Asmara: Red Sea Press, p. 8.

- Al-Shabaab means “The Youth” in Arabic. It emerged as the radical youth wing of Somalia’s now-defunct Union of Islamic Courts, which controlled Mogadishu in 2006, before being forced out by Ethiopian forces.

- Adam, Hussein M. (2009) Political Islam in Somali History. In Hoehne, Markus and Luling, Virginia (eds) Milk and Peace, Drought and War: Somali Culture, Society and Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 122.

- Lewis, Ioan M. (2010) op. cit.