Introduction

In the post-World War II period, two broad conceptualisations of justice can be identified: survivor justice and victor’s justice. This article focuses only on survivor justice as a model more suitable to African contexts, where conflicts are mostly internal and there are rarely decisive military victories between political adversaries. Survivor justice is a form of transitional justice that aims to transcend the binary of victim/perpetrator by combining impunity for all participants with political reform that transforms institutions of society. Survivor justice is based on a complete transformation of society emerging from mass violence.1 It redefines the victors and the vanquished as survivors after mass violence, allowing both to coexist in a reformed political community. It also reconciles the logic of rights and justice with reconciliation and peace in a context where there is no decisive winner. Survivor justice prioritises the living over the dead.

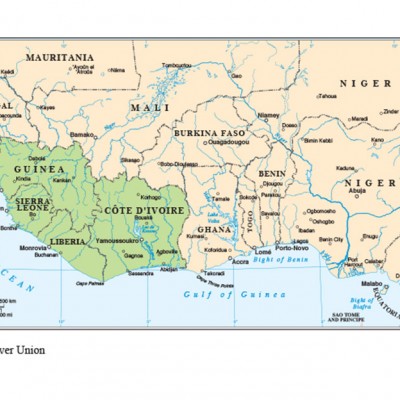

To avoid the problem of pitting peace against justice, I will first distinguish between forms of justice, and view peace and justice as complementary and not opposites. The research question is: what is the potential for advancing contemporary peace processes and negotiated agreements through the notion of survivor justice? In this article, I argue that in contexts where a decisive military victory is untenable, survivor justice – that is, political reform combined with judicial reconciliation – is the best way to resolve Africa’s intractable conflicts. First, I introduce and develop the conceptual framework of survivor justice. Second, I critique the universalisation of human rights discourse around justice. Third, I discuss survivor justice in peace agreements in the context of mass violence, and then in the case of Rwanda and how it has implemented survivor justice in dealing with the aftermath of the 1994 genocide through indigenous institutions known as gacaca.

Peace and Survivor Justice

To answer the question: ‘what is the potential for advancing contemporary peace processes and negotiated agreements through the notion of survivor justice?’, the intellectual legacy of modern-day human rights discourse and the distinction between two main conceptualisations of justice need to be understood. In his critique of the tendency to universalise human rights discourse, Anthony Pagden writes that “if we wish to assert any belief in the universal we have to begin by declaring our willingness to assume, and to defend, at least some of the values of a highly specific way of life”.2 Pagden argues that the genesis of human rights and natural rights, which later gave birth to international law and global justice, needs to be understood as part of the liberal tradition of rights that goes back to the Greeks and Romans. The liberal tradition is intricately connected to a history of European imperial expansion, which later gave birth to liberal peace. Pagden also argues that the tradition out of which we get our modern-day human rights convention excluded many other traditions (African, Asian and various indigenous traditions around the world), and calls for a cautious embrace of today’s commonly accepted discourse on rights. The notion of survivor justice arises in response to a dilemma of conflicts in plural and divided societies about how to end ongoing violence and how to ensure justice and reconciliation. In Africa, Mahmood Mamdani has argued that we need to distinguish between different forms of justice to create a space where conflict resolution can take place. Mamdani proposes survivor justice, which takes survivors as a starting point and prioritises reform over prosecution.3 This challenges the belief that reform can only come through the court (trials), as the only viable alternative to dealing with the aftermath of mass violence. This articulation is increasingly gaining support in places where conflict is intractable and victory untenable through military means.

Furthermore, Mamdani notes: “[I]f one insists on distinguishing right from wrong, the other seeks to reconcile different rights. In a situation where there is no winner and thus no possibility of victors’ justice, survivors’ justice may indeed be the only form of justice possible.”4 Victor’s justice – which, according to Mamdani, is represented by the Nuremberg trials – is premised on certain liberal assumptions, namely decisive military victory over an adversary, and separation of victims and perpetrators (for example, the birth of the state of Israel). In another article, Mamdani puts survivor justice in context and explains why it paved the way for South Africa’s transition in the 1990s.

Mamdani writes:

If South Africa is a model for solving intractable conflicts, it is an argument for moving from the best to the second best alternative. That second best alternative was political reform. The quest for reform, for an alternative short of victory, led to the realization that if you threaten to put the leadership from either side in the dock they will have no interest in reform. This change in perspective led to a shift, away from criminalizing or demonizing the other side to treating it as a political adversary.5

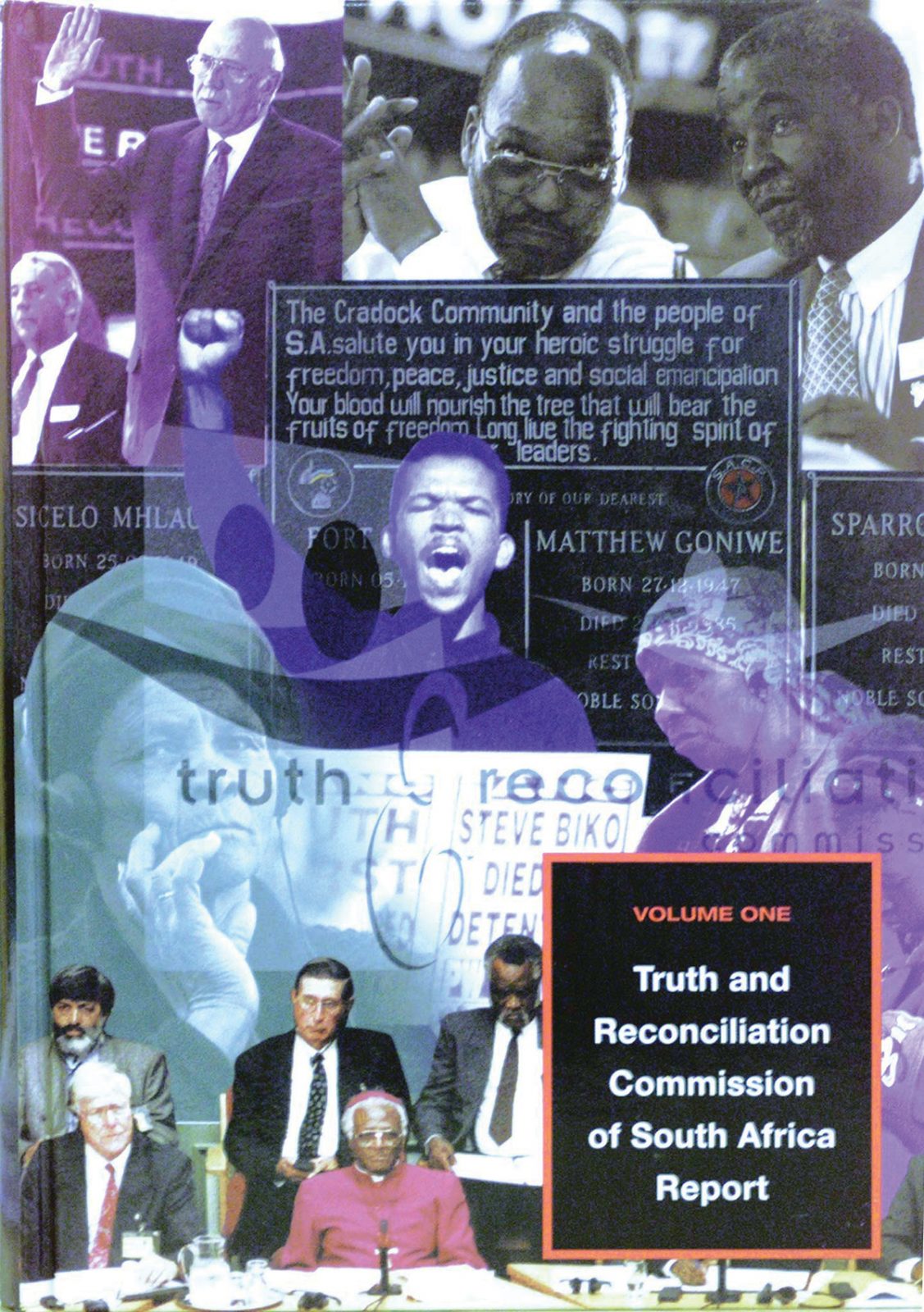

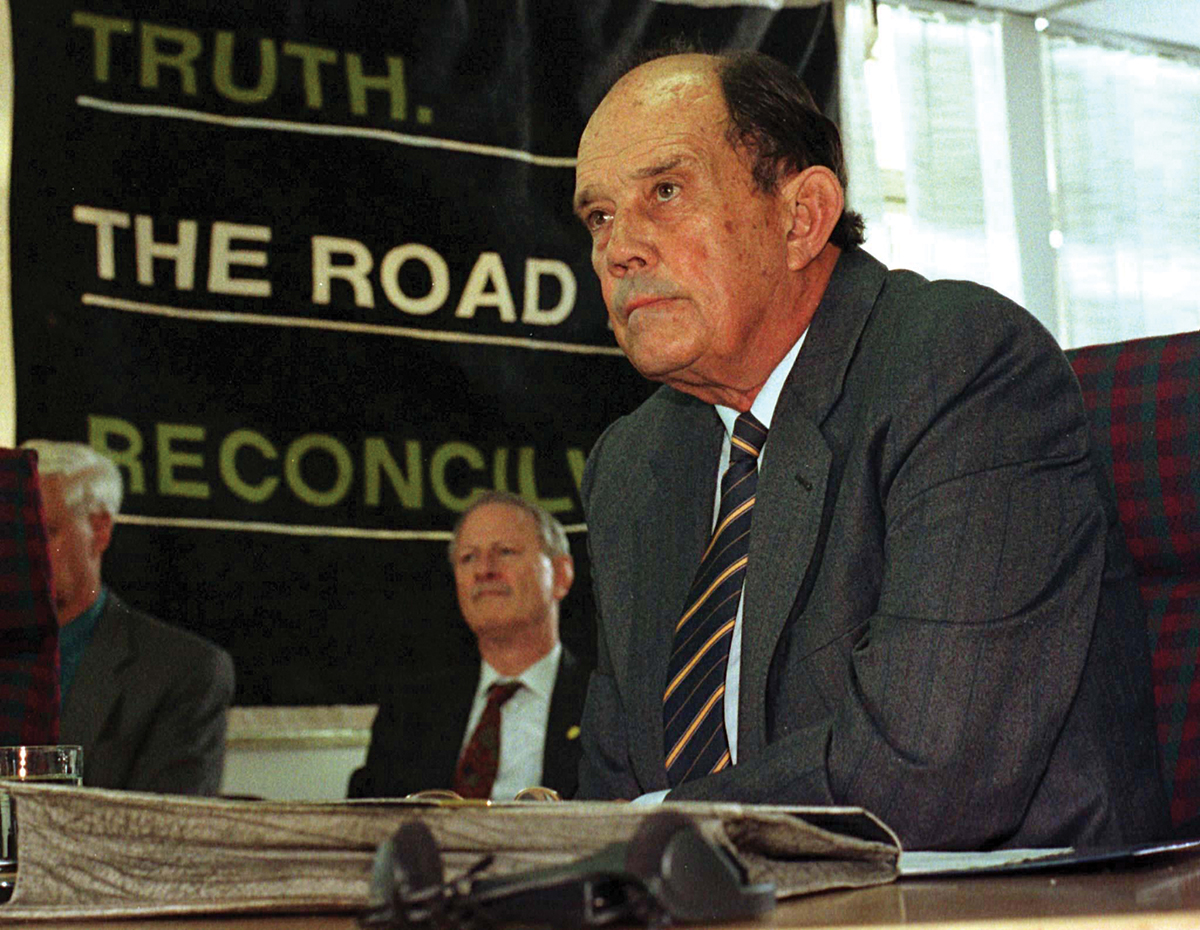

In cases where victims, survivors, beneficiaries and former perpetrators must live side by side, there is a need to rethink the model of criminal justice and instead shift the discussion towards survivor justice. Survivor justice – which Mamdani associates with post-apartheid transition – then combines impunity with political reform (political settlement) and judicial reconciliation (Truth and Reconciliation Commission/TRC).

the Union Building after the inauguration ceremony (10 May 1994). GALLO IMAGES/ REUTERS/JUDA NGWENYA

Today, one finds two competing conceptualisations of justice that are championed by various actors in the international community. On the one hand, human rights organisations advocate for the prosecution of perpetrators of violence.6 For many of these organisations, criminal justice is an indispensable key to peace. On the other hand are scholars and policymakers, who want a pragmatic approach to ending violence. The challenge for many countries in Africa is how to end violence and create the space where issues of justice and reconciliation can be discussed and negotiated. In South Africa, for example, it was only after the formation of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) I and II, followed by the negotiated settlement at Kempton Park and the decriminalisation of the African National Congress (ANC), that the path to peace – and, ultimately, transition – was opened.7 Without first reaching a political settlement, it would have been difficult for South Africa to transition to a democracy. The question that many plural societies in Africa face is how to end violence (end of hostilities), hold perpetrators accountable (justice) and achieve peace (conflict transformation). In a situation where one needs those in power to reach a settlement, demanding criminal justice is tantamount to demanding the impossible when a military victory is untenable. This is where survivor justice is useful as an alternative or a second-best solution to an intractable conflict.

Commission in South Africa. In his testimony Malan urged the Commission to forget about revealing apartheid crimes

so that the country could bury the past and build the future. GALLO IMAGES/ REUTERS

Survivor justice does not advocate for blind impunity and blanket amnesty. It distinguishes between forms of justice by prioritising the living over the dead, proposing a combination of impunity combined with reform, and sequences the process of transitional justice.8 This sequence of processes is well summarised by Jok Madut Jok, who advocates for a sequential approach to the ongoing peace process in South Sudan, to avoid “the temptation to rush for a bad peace deal which returns the country to war versus the prolonged peace process that risks the loss of more human lives but produces a sustainable peace”.9 At the core of survivor justice is not a trade of peace for justice, but an exchange of “amnesty for the willingness to reform”.10 How would survivor justice work in the intractable conflicts in Africa? A number of key processes can be sequenced on multiple tracks (if necessary) over time. According to Jok, this entails:

…a sequential peace process, beginning with an enforceable cessation of hostilities and followed by a negotiated settlement, even if that settlement is between the elite, and an insistence by the mediators on a strong political and financial commitment from the parties to a programme of post-war reconstruction, institutional reform, especially a strong security sector reform, justice, accountability for war crimes, national dialogue, healing and reconciliation.11

In a sense, survivor justice delays criminal proceedings to give negotiated settlements a chance. This often begins with a negotiated ceasefire, followed by a political settlement, and then issues of transitional justice are built into the process or sequenced on a separate track from the negotiated agreement among conflict parties.

Survivor Justice and Negotiated Peace Agreements

Justice is important in peace processes.12 In the literature on violence and negotiated settlements, there is a lively debate on why some conflicts are successfully negotiated and others remain intractable and insoluble; why negotiators fail in one context and succeed elsewhere. There is increasing evidence that the process and content of agreements – as well as the different forms of justice – play a crucial role in settling disputes during negotiations. There is a relationship between negotiations (content and process) and the durability of negotiated peace agreements.13 Two forms of justice are particularly relevant to survivor justice: procedural justice and distributive justice. Daniel Druckman and Cecilia Albin note that justice can complicate the peace process, when various competing forms and principles of justice are championed by the conflict parties.14 I. William Zartman and Viktor Aleksandrovich Kremeniuk, in their studies of conflicts from the Thirty Years’ War to the Napoleonic Wars, and many wars in the 20th and 21st century, found that various conceptualisations of justice led to different outcomes in conflicts. They call these forms “forward-looking” and “backward-looking” principles of justice.15 The former is positive-sum justice that looks to the future, whereas the latter justice is preoccupied with issues of the past. Zartman and Kremeniuk refer to Mamdani’s distinction between survivor justice and criminal justice. When Druckman and Albin analysed 16 peace agreements, they found that “[a]greements with equal treatment and/or equal shares were associated with highly forward-looking outcomes and high durability, and equal measures with a more backward-looking outcome and poorer durability”.16 In other words, agreements that were forward-looking and based on survivor justice principles led to positive outcomes and high durability. These findings have support in the African context: South Africa, Mozambique and Sudan all had negotiated settlements that were based on the principles of survivor justice.17 In the context where criminal justice has been invoked – in conflicts in Sudan (an example of both types of justice), Uganda and elsewhere in Africa – the effects mostly have been the prolongation of violence.18 In the case of Sudan, the major axis of conflict (north/south) was brought to an end through the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), while the conflicts within the Republic of the Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan continue.19 This partly explains the decision of the negotiators in South Africa, Mozambique and Sudan to subordinate criminal justice to prioritise survivor justice. Successful agreements that are durable depend on two issues in relation to justice: procedural justice (the fair representation of stakeholders or inclusivity) and the degree to which issues are addressed during negotiations.20

Andrew Natsios, US Special Envoy to Sudan between 2006 and 2007, noted:

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement says not one word about prosecuting war crimes or compensating the victims of atrocities for just this reason: back in 2003, during the peace negotiations, Garang wisely realized that if he demanded justice, the north–south war would not end (he also knew the southerners had committed their share of atrocities). Instead of war crimes trials, the South African model of a truth and reconciliation commission might be considered.21

Given the evidence that different conceptualisations of justice have different effects on negotiated peace agreements, the question that arises is whether human rights organisations have been wrong in promoting criminal prosecution within the process of ongoing peace talks, or is the position taken by continental organisations (like the African Union) – to defer indefinitely the publication of reports of inquiry into violence on the continent in order to prioritize peace talks – the better option? Both groups are right, to an extent. Victims need to know that perpetrators are held to account under the law. This needs to be negotiated, alongside the pressing need to allow the peace talks to deliver peace through a negotiated settlement. How does one find a middle ground between these two positions? It is achieved through the sequencing of transitional and peace processes by prioritising different forms of justice at different stages. This continues through the enforceable cessation of hostilities, a negotiated settlement (whether it is inclusive or only between elites), commitment from all conflict parties to reform (as in the South African example), security sector reform (key in the case of South Sudan), and the formation of transitional justice mechanisms (such as truth commissions, national dialogues, and healing and reconciliation mechanisms). The timing and sequence of these processes are key. The exception to a negotiated settlement and sequenced processes is the case of a decisive military victory – for example, that of the Allied powers’ victory over the Axis powers during World War II.22 In cases where there is no decisive military victory, negotiated settlements and survivor justice offer the best alternative to ending violence, thus paving the way to durable peace.

from prison and the two men meet to talk about what happened (February 2003). GALLO IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES/ PER-ANDERS PETTERSSON

The following section presents a case study to illustrate the contemporary implementation of survivor justice principles, using a hybrid model based on indigenous institutions in Rwanda.

Gacaca: Survivor Justice in Rwanda

Survivor justice by itself, without reform and other complementary transitional mechanisms, cannot lead to durable peace. To deal with the aftermath of the Rwanda genocide, the government pursued a three-pronged approach that combined various forms of justice (criminal and survivor) and formed three sets of institutions: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the national court system and the Gacaca courts. The Gacaca courts are an indigenous justice mechanism, where the involvement of lawyers is prohibited and reconciliation is the driving principle.23 Gacaca is also a form of restorative justice24 based on survivor justice principles, whereas the Arusha Tribunal represents criminal justice principles. Following the South African model, the Gacaca courts grant short sentences when a person is repentant and seeks reconciliation with the community,25 lending support to the emerging paradigm of political reform combined with judicial reconciliation as an alternative to dealing with legacies of mass violence. These courts have processed one million cases over 10 years at a cost of US$40 million, and are the centrepiece of Rwanda’s justice and reconciliation process. Gacaca is now seen as the way forward, due to its ability to reform former perpetrators and reintroduce them into society at very low cost compared to the traditional, Western court system. The Arusha Tribunal included a total of 69 trials, at a total cost of US$1 billion.26 According to Phil Clark: “A vast genocide caseload – as many as one million cases – has been handled by Gacaca courts in a decade. In fifteen years the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), based in Arusha, has completed 69 trials. Gacaca has cost about US$40 million, the ICTR more than US$1 billion.”27 In this regard, countries that have prioritised reconciliation over criminal justice have had to balance justice, truth, peace and security. Rwanda shows that criminal justice can be complementary to other forms of justice when it is sequenced over time and embedded in indigenous institutions.

Conclusion

This article began with the question of what the potential is for advancing contemporary peace processes and negotiated agreements through survivor justice. It presented and discussed the case of survivor justice, its underlining assumptions and the context that gave rise to its usage in the African context (South Africa, Rwanda, Mozambique and Sudan) in advancing contemporary peace processes and negotiated agreements. Survivor justice should be seen as a second-best alternative to decisive military victory. Many conflicts in Africa are internal, civil war-type conflicts, where attempts to achieve victory are untenable. The United Nations also recognised that the “majority of perpetrators of serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law will never be tried, whether internationally or domestically”.28 This realisation has contributed to making the case for survivor justice as a way of facilitating the settlement of ongoing conflicts and reconciliation in the aftermath of violence. The cases of South Africa (CODESA/TRC) and Rwanda (Gacaca) illustrate the successes of survivor justice in post-conflict contexts.

In South Africa, criminal justice was subordinated to survivor justice. In Rwanda, survivor justice has been prioritised as the Gacaca courts combine retributive and restorative justice. In both cases, a sequential approach to reform was adopted. These approaches represent a trade-off between impunity and structural reform (with less institutional reform in the latter case than the former). Survivor justice is not confined to Africa. Mamdani shows that it can be seen in practice “from post-Franco Spain, to Latin American transition to civilian rule and electoral democracy”.29 The future of durable peace in Africa, and other contexts where violence is ongoing and a negotiated settlement is difficult to reach, rests on a flexible mechanism that combines political reform with judicial reconciliation, built on a hybrid foundation of local institutions and regional/international best practices to complement domestic institutions. Justice that avoids zero-sum logic is more viable in the search for durable peace in divided societies where decisive military victory is untenable.

Endnotes

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. and Corporation Ebooks (2016) The Decolonial Mandela: Peace, Justice and the Politics of Life. New York: Berghahn Books; Mamdani, Mahmood (2001) When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton: Princeton University Press; Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) (1999) Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Vol. 1. Cape Town: The Commission.

- Pagden, Anthony (2003) Human Rights, Natural Rights, and Europe’s Imperial Legacy. Political Theory, 31 (2), p. 173.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2014) Beyond Nuremberg: The Historical Significance of the Post-apartheid Transition in South Africa. Politics & Society, 43 (1); Mamdani, Mahmood (2009) Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2008) The New Humanitarian Order. Nation, 287 (9), p. 22.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2014) op. cit., p. 67.

- Human Rights Watch (2015) ‘South Sudan: AU Putting Justice on Hold’, Available at: <http://www.hrw.org/news/2015/02/03/south-sudan-au-putting-justice-hold>; Amnesty International (2015) ‘South Sudan: African Union Peace and Security Council Stands in the Way of Justice in South Sudan’, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/articles/news/2015/01/south-sudan-african-union-peace-and-security-council-stands-way-justice-south-sudan/>.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2014) op. cit.; Asmal, Kader, Asmal, Louise and Roberts, Ronald Suresh (1997) Reconciliation through Truth: A Reckoning of Apartheid’s Criminal Governance. Cape Town/Oxford/New York: David Philip Publishers, James Currey Publishers, St. Martin’s Press; Viljoen, Gerrit and Venter, François (1995) A Culture of Negotiation: The Politics of Inclusion in South Africa. Harvard International Review, 17 (4).

- Jok, Jok Madut (2015) ‘Negotiating an End to the Current Civil War in South Sudan: What Lessons Can Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement Offer?’ Inclusive Political Settlements Papers, 16 (September), Available at: <http://ips-project.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IPS-paper-16-Negotiating-an-End-to-the-Current-Civil-War-in-South-Sudan.pdf>; Kriesberg, Louis (2001) Changing Forms of Coexistence. In Abu-Nimer, Mohammed (ed.) Reconciliation, Justice, and Coexistence: Theory & Practice. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books; United Nations Security Council (2004) ‘The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-conflict Societies. Report of the Secretary-General’, Available at: <http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/SSAJ152.pdf>.

- Jok, Jok Madut (2015) op. cit., p. 15.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2014) op. cit., p. 66.

- Jok, Jok Madut (2015) op. cit., p. 14.

- Druckman, Daniel and Albin, Cecilia (2012) The Role of Equality in Negotiation and Sustainable Peace. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 5 (1); Druckman, Daniel and Albin, Cecilia (2011) Distributive Justice and the Durability of Peace Agreements. Review of International Studies 37 (3); Hayner, Priscilla (2007) ‘Negotiating Peace in Liberia: Preserving the Possibility for Justice’, Available at: <https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ICTJ-Liberia-Negotiating-Peace-2007-English_0.pdf>.

- Druckman, Daniel and Albin, Cecilia (2010) The Role of Justice in Negotiation. In Kilgour, D. Marc and Eden, Colin (eds) Handbook of Group Decision and Negotiation. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; Zartman, I. William and Kremeniuk, Viktor Aleksandrovich (2005) Peace Versus Justice: Negotiating Forward- and Backward-Looking Outcomes. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Druckman, Daniel and Albin, Cecilia (2010) op. cit., p. 10.

- Zartman, I. William and Kremeniuk, Viktor Aleksandrovich (2005) op. cit.; ibid.

- Druckman, Daniel and Albin, Cecilia (2010) op. cit., p. 109.

- Zambakari, Christopher (2012) In Search of Durable Peace: The Comprehensive Peace Agreement and Power Sharing in Sudan. The Journal of North African Studies, 18 (1).

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2008) The Question of Justice – Lessons and Challenges. Speech delivered at the Kenya Human Rights Commission’s annual human rights lecture on 15 December, Available at: <http://www.capitalfm.co.ke/news/2008/12/scholar-s-views-on-seeking-justice/>; Zambakari, Christopher (2012) op. cit.

- There are currently various peace processes underway in North and South Sudan, amidst ongoing conflicts. In August 2015, the Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS) was brokered under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). It remains to be seen whether ARCSS will hold and bring peace to a war-torn South Sudan.

- Hayner, Priscilla (2007) op. cit.

- Natsios, Andrew S. (2008) Beyond Darfur. Foreign Affairs, 87 (3), p. 90.

- Even with the Nuremberg Trial and Tokyo Trial, there were many exceptions to the fully-fledged implementation of criminal justice. The best example is the trial of Alfried Krupp, a leading German industrial magnate and major arms manufacturer for Germany from the 1840s to the end of World War II. The trial of the Krupp family demonstrated the imperfection of justice, or selective enforcement and centrality of power in its enforcement. The United States not only cut short the sentence, but Krupp was set free and his wealth restored. See Mamdani, Mahmood (2014) op. cit., pp. 65–66.

- Clark, Phil (2012) ‘How Rwanda Judged its Genocide’, The Counterpoints, Available at: <http://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/files/counterpoints/docs/How-Rwanda-judged-its-genocide-E6QODPW0KV.pdf>, p. 1.

- Tiemessen, Alana Erin (2004) After Arusha: Gacaca Justice in Post-Genocide Rwanda. African Studies Quarterly, 8 (1), p. 58.

- Outreach Programme on the Rwanda Genocide and the United Nations (2014) ‘Background Information on the Justice and Reconciliation Process in Rwanda’, Available at: <http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/pdf/Backgrounder%20Justice%202014.pdf>.

- Clark, Phil (2012) op. cit., p. 7.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- United Nations Security Council (2004) op. cit., p. 15.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2008) op. cit.