Executive Summary

Liberia is at a critical juncture in terms of its ability to maintain its hard-won peace and ensure that its reconciliation and sustainable development efforts are not derailed. The West African country, with a population of 3.124 million,1 celebrated ten years of peace in 2013, following brutal civil war (1989–97 and 1999–2003) that resulted in the loss of over 200 000 lives, displacement of over one million people,2 destruction of livelihoods and paralysis of governance structures. Starting in 2009, Liberia began to take important steps to rebuild relationships, reconcile divided communities, rejuvenate institutions and structures, and set a progressive agenda for economic growth and development. Efforts to decentralise governance and social services, and to ensure citizens’ enjoyment of security and stability were integral to moving the country forward. The March 2014 Ebola outbreak severely affected peacebuilding work and threatened to undo progress made during the previous six years.3 During the epidemic, approximately 10 564 Ebola cases were reported and 4 716 people confirmed dead. This Policy & Practice Brief (PPB) argues that the crisis which resulted was not a health emergency, peacebuilding issue or development challenge alone; it is related to all three fields and, in Liberia specifically, should be viewed as interlinked. It maintains that divisions between the peacebuilding and development sectors and their objectives are increasingly being closed, and that the challenges raised by, and responses to the Ebola crisis illustrate this well. The brief analyses key challenges facing the nation, and provides recommendations on the way forward in advancing the country’s sustainable development, peacebuilding and health systems strengthening agendas. It is hoped that these ideas will be useful to the work of Liberian and international peacebuilding actors alike.

Introduction

Liberia was founded in 1822 as an outpost for returning freed slaves from the United States of America (USA) and the Caribbean. It grew into a colony, became a Commonwealth country and eventually gained its independence on 26 July 1847 with the help of the American Colonization Society.4 Descendants of the freed slaves, known as Americo-Liberians, remained in social and political control of the country until 1980. Despite efforts to achieve a more equitable and just society for all, the nation experienced violent civil conflict which started in 1989 and ended 14 years later in 2003.5

A Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in August 2003 ended the bloody war and ushered in a period of relative stability by forming the basis for the establishment of a transitional government.6 In October 2003, the United Nations (UN) took over peacekeeping operations from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and established the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL). The dual impact of the CPA and the presence of UNMIL significantly bolstered the country’s relative peace, seeing the nation through two successive democratic elections and the steady development of its economy and institutions, which had been devastated during the war.7 During the years that followed, active disarmament, demobilisation rehabilitation and rebuilding efforts were implemented. In 2005 Liberia held elections that most local and international observers considered to be free and fair.

To further consolidate peace and move the country forward, in 2012 Liberia formulated its Vision 20308 through a highly participatory and inclusive process that was launched by President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf. The development of the roadmap was driven by two national frameworks – the Agenda for Transformation (AFT) (2012–17) and the Strategic Roadmap for National Peacebuilding, Healing and Reconciliation (2012–30). Both plans reinforce each other and support efforts to achieve lasting peace and reconciliation, enhance security, and uphold the rule of law. As a result of these interventions, Liberia’s economy gradually grew and public services were decentralised from the capital, Monrovia, to cover other parts of the country. In particular, 11 projects9 designed from the Strategic Roadmap for National Peacebuilding, Healing and Reconciliation valued at over US$15 million over three years (2014–16) were implemented with financial support from the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund (UN PBF), in conjunction with the UN Peacebuilding Commission (UN PBC) and the UN Country Team, as well as UNMIL and civil society organisations (CSOs). From 2008 to mid-2015, the UN PBF contributed over US$50 million towards three peacebuilding priorities: security sector reform (SSR), rule of law and promoting national reconciliation. As mentioned earlier, these interventions aim to ensure that Liberia promotes democratic governance, maintains peace and stability, enhances economic growth and achieves social cohesion.

In line with the above initiative, and to support the deployment of police officers to counties and rural communities to enhance confidence in the country’s security infrastructure, regional justice and security hubs were launched in central Liberia. These hubs:

- provided more decentralised access to security and rule of law services

- enhanced citizens’ trust in the security apparatus

- reduced pre-trial detention periods through employing and deploying more public defenders

- supported better maintenance of cross-border security by providing technical and logistical support to Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization personnel.

Despite these interventions, and the fact that Liberia made significant progress in building and sustaining peace in the years following the signing of the CPA, there are a number of challenges that the government still needs to address. A primary consideration in the government’s approach to these issues is the underlying acknowledgement that sustainable peace in Liberia cannot merely be based on the absence of war, but should be measured by the sense of security, safety and peace that Liberians feel. Liberia’s post-war peacebuilding environment has been characterised by the establishment and development of broad structures and institutional frameworks that incorporate a substantial range of local, regional and international actors, and which seek to address the root causes of conflict in the country.10 The nation was dealt a blow in March 2014 – which threatened progress made – as it confirmed its first Ebola case.

The outbreak of the Ebola virus

On 30 March 2014, Liberia confirmed its first two cases of patients with the Ebola virus. By 23 April there were 34 cases and six deaths, and by 17 June 16 people had died. On 30 July Liberia closed its schools and on 13 November a state of emergency was declared.11 The outbreak affected peacebuilding activities, led to declines in economic growth and undermined foreign direct investment as a result of slow-down in, and termination of some, economic operations. At the same time, while existing tensions and conflicts in the country were exacerbated, new ones also threatened to emerge.12

Fear, distrust and insufficient communication and knowledge about the Ebola virus among the general populace encouraged its spread. Ebola was a new phenomenon for most Liberians, and for the majority of citizens in the two other countries affected – Guinea and Sierra Leone. Health professionals, largely unfamiliar with the virus, initially encountered difficulties in diagnosing the disease because Ebola symptoms are similar to those of other illnesses; among them malaria, typhoid and diarrhoea. Confusion in diagnoses, coupled with the generally poor infrastructure that characterises many health centres in Liberia, delayed immediate intervention by the government and international community, which could have halted or at least slowed the epidemic in its early stages.

Customary practices in Liberia, as in many other communities in Africa, where friends and relatives provide physical care for the ill, and wash and clothe their dead in preparation for burial, were said to have contributed to the rapid spread of Ebola in the country. While lack of knowledge about how the virus is spread in the context of high levels of poverty limited individuals’ abilities to protect themselves from infection, the same poverty and poor health infrastructure prevented people from being tested. The conditions in which Liberians lived directly correlated to the spread of the disease: if the living conditions had been better, the virus might not have spread so wide so fast. Fear of being quarantined, and becoming infected at health centres, plus the fact that during the early stages there was no treatment available, discouraged people from testing for Ebola, and negatively impacted citizens’ health-seeking behaviour for other conditions during this time. Stigma and discrimination suffered by infected persons, those who survived, and their families also negatively affected Liberian’s willingness to be tested.

Relatives were reportedly unwilling to take in bodies for safe disposal at designated points, because standard protection against the further spread of Ebola involved burning the mattresses, bedding and clothes of the infected and deceased. Communities, particularly those in poorer areas, were reluctant to cooperate with medical teams or those responsible for monitoring contacts. In extreme cases, health workers and people involved in tracing contacts were threatened or physically assaulted, resulting in them requiring the services of security and protection personnel. Lack of experience in treating the disease and knowledge about how it is transmitted caused delays in communicating information about self-protection through, for example, hand-washing and avoiding direct handling of the ill and deceased. Later, these simple practices proved essential in individuals’ efforts to avoid contracting Ebola and spreading it. Understanding and accepting the nature of Ebola took more than four months from the time the first cases were reported. At the same time, poor communication, difficulties in disseminating accurate information, and mistrust of the government and its structures meant that citizens were hesitant to believe the accuracy of information that could potentially have saved lives.

At the onset of the epidemic, Liberia’s health system was unprepared for the challenges presented by the virus. Even though the government took some bold decisions, including declaring a state of emergency, there were limited preventive measures initially implemented to arrest the disease. Once the epidemic hit, at best the government failed to adequately engage communities in its initiatives and at worst authorities stifled local cooperation with disease control efforts, among them the quarantines imposed. The Ebola outbreak initially exacerbated the existing lack of coordination among government institutions, as various ministries competed for resources and authority over the response. Similarly, competition for donor funding impaired collaboration between civil society organisations and the government. The declaration of a 90-day state of emergency in November 2014 was made in conjunction with the announcement of other preventative measures, including instructions for non-essential government employees to remain at home for 30 days, the closure of schools, shutting down of markets in affected areas, and restrictions placed on social gatherings and movements between counties. Although necessary, these procedures severely limited social interactions and destroyed the livelihoods of employees and service providers – teachers in private schools and local traders for example – resulting in significant challenges for many in Liberia.

The country, characterised by structural inequality, poverty and weak governance, was ill-equipped to deal with the outbreak of Ebola. For a country that had previously experienced a violent civil war as a result of these factors, it was not improbable that the Ebola crisis could have led to civil unrest, particularly because quarantines enforced in some areas of Monrovia and restrictions placed on the performance of certain burial rituals angered Liberians, particularly young people. The Ebola crisis highlighted the structural weaknesses of the government and the country, and contributed to existing threats to peace and security, and the country’s stability.13

The health crisis brought up threats to peace and security. Many citizens were in a state of denial about the origins and modes of transmission of the virus and, through various conspiracy theories and myths, some blamed the former on external forces. So pervasive was the lack of knowledge and disavowals that in some parts of Liberia, health centres and medical institutions were attacked because residents believed that medical personnel were responsible for the virus spreading. Further, there were tensions stemming from the government’s building of isolation centres, which communities resisted, arguing that they were not consulted, and that this would bring Ebola closer to their places of residence.14 These perceptions presented significant challenges for the government’s response.

Ebola’s negative impact on peacebuilding

As a result of the Ebola outbreak, much of the progress made in consolidating peace in Liberia came to a halt while focus was placed on addressing the health crisis. Now that, as of May 2015, Liberia is Ebola-free the country faces the challenge of re-igniting past measures to consolidate peace, and to address the new challenges it is faced with.

Declining economic growth

The Ebola crisis reduced growth and increased inflation in Liberia. So dire was the situation that the Finance Minister, Amara Konneh, warned the country to brace itself to feel the effects of a shortfall of US$115 million in the 2014 budget.15 The epidemic negatively impacted personal income, investment and export rates, with a corresponding shortfall in the agricultural sector caused by the closure of some businesses and industrial operations, including those in the mining and cash crops sectors. The labour force was diminished due to deaths, and the mass exodus of expatriates from the country. At the same time, the burden on households increased, workers migrated to escape the disease, or stayed away from their places of employment, and farmers were unable to harvest crops. All in all, the economy declined drastically, revenue intakes dropped, and available financial resources for programmes and projects were redirected to the health sector.

Ebola raised uncertainties about investing in the country. To curb onward transmission of the virus, the Government of Liberia imposed various restrictions on trade, insisted that markets should close, put in place travel restrictions and quarantines, and banned public gatherings at places such as bars, restaurants and entertainment centres. As well as impacting the freedom of citizens to move and congregate, these measures also contributed to rising unemployment and price hikes as a result of disruptions in the supply of commodities. This further depressed household consumption, making already tough living conditions worse for ordinary Liberians.

The situation worsened when neighbouring countries shut their borders with Liberia, further limiting movement and isolating the country and its inhabitants. In October 2014, as the crisis started to escalate, over 15 African countries had closed their borders to citizens of the affected countries. This isolation worsened the economic impact the virus had on all countries involved, and resulted in major setbacks in progress towards regional integration in Africa.16

Ebola contributed to sharp declines in domestic food production, mining activities, the hospitality industry, and transport services in Liberia. The country’s agricultural sector, which employs over two thirds of the rural population, was particularly affected, with experts predicting decreases in 2015 agricultural growth from 3.5 to 1.3 per cent.17 In addition to declines in economic activity, Liberia was also faced with the real threat of increasing food prices, on top of the crisis caused by challenges in the farming sector.18

Liberia’s economy depends heavily on natural resources, including those in the mining sector, for revenue and jobs. In 2012, the country’s total proceeds from natural resources accounted for 26.1 per cent of the country’s GDP. The Ebola epidemic disrupted supply chains and forced a slowdown in growth and, in some case, the closure of mines. ArcelorMittal, the largest mining company operating in Liberia, had to postpone its planned investment to expand production capacity while China Union, the second-largest enterprise, shut down operations in the country completely in August 2014. As a result, the World Bank predicted Liberia’s overall growth at only 1.3 per cent, down three per cent from earlier forecasts.19

Perceptions about the disease also played a significant role in shaping its course in Liberia and externally. Despite the fact that the virus only seriously affected three countries out of 54 on the continent, economic growth across Africa was adversely affected. In the Gambia, where tourism contributes 12 per cent of the country’s GDP, hotel reservations dropped by 65 per cent; in Lagos, Nigeria, commercial businesses reported a market decline in sales estimated at between 20 and 40 per cent; while in Senegal, hotel occupancy dropped by over 40 per cent.20

Widening socio-cultural divisions

Ebola severely impacted, and at times reversed, progress in the social sector and created additional needs that require short-, medium-and long-term interventions to address. Deteriorating personal incomes, combined with a breakdown in social cohesion, undermined cooperative networks at community and district level. Increasing community resilience in the face of challenges, while desirable, had negative consequences for the long-term security of Liberian families, as they coped by selling productive assets such as land, houses and livestock to generate income. Uptake – as well as provision – of health services unrelated to Ebola also sharply declined, with significant decreases in attendance at hospitals, as citizens feared contracting the virus during visits. Throughout this period, pregnant women and other patients turned to traditional birth attendants and traditional healers respectively for care, due to fears of getting sick, as well as a widespread shortage of personnel at health centres as nurses and doctors also succumbed to the disease.

Schools shut down and, for many students, the epidemic led to postponements in their graduation from secondary and tertiary institutions across the country. Even though most schools had reopened by mid-2015, (re-)enrolment remained a challenge for many due to financial resources caused by the death of parents and/or relocation to new homes after being orphaned or losing guardians and other family members.

Local capacities for the maintenance of peace and stability were weakened, with allegations of lack of interest on the part of the government. Added to this were accusations that the administration contributed to the destruction of traditional values and cultures through, for example, introducing and insisting on the cremation of bodies, sometimes en masse, instead of burying. No matter how practical the reasons behind the instruction, this phenomenon, which was previously unheard of in the Liberian cultural context, was unwelcome and resented by those affected. Overall, the socio-cultural impact of the Ebola crisis is an important aspect to address as the social tensions it caused have the potential to escalate and result in violence going forward.

The role of governance and elections

Elections are a transformative tool for democratic governance. They are the means through which people voice their preferences and choose their representatives as well as a conduit for government’s demonstration of its commitment to democracy.21 There is consensus that the many problems, such as corruption and poverty, which affect Liberia have their roots in poor governance. Presidential and legislative elections in 2011 served as a test for the consolidation of electoral democracy in the country.

The Ebola epidemic affected senatorial elections scheduled for October 2014, forcing their postponement to December 2014 as citizen participation would have been affected by the travel ban and persisting concerns about spreading and contracting the virus. Encouragingly, when they were eventually held, the polls were considered a success. The government and people of Liberia are, however, fully aware that the possibility of violence in the future remains real and that preparations for successful and violence-free elections in 2017 need to begin now, particularly taking into consideration that citizens’ trust in the government is low, and that civil service capacity has been affected, as many officials left the country during the outbreak, resulting in the dereliction of their duties.22

The October 2017 elections will be a litmus test for Liberia’s organisation of presidential elections, a watershed and measure of sustained stability. Moving forward the National Elections Commission, working with civil society organisations and development partners, should be encouraged to take appropriate measures to avoid major electoral irregularities in the future, while all political parties bear the primary responsibility of ensuring adherence to and respect for the law.

Analysing Liberia’s response to the Ebola crisis

The Ebola epidemic could have easily undone all progress made in Liberia since the end of the civil war. This did not happen, however, primarily because the leadership demonstrated urgency in its responses, through frequent communication to citizens, and being visible and present on the ground, particularly at outbreak sites. Also of importance is that health officials and their partners were quick to recognise the importance of community engagement. Health teams understood that community leadership brings with it well-defined social structures, with clear lines of credible authority. Teams worked hard to win support from village chiefs, religious leaders, women’s associations and youth groups.23 In analysing why Liberia recovered faster and better from the Ebola outbreak than did neighbouring Guinea and Sierra Leone, three main factors are significant. These are discussed below.

1. The government’s response

The Government of Liberia’s response to the epidemic has been both commended and criticised. There are some who are of the opinion that the government’s use of national security forces to limit citizens’ movements to quell the spread of the virus was too intensive and, combined with the quarantine of certain areas in the capital, caused more panic among communities. They further maintain that the government could have done more to address speculation by some Liberians that Ebola was created by the administration as a means of sourcing funds from the donor community.24 For their part, health workers and doctors criticised the government’s handling of the crisis because, they argued, the death toll could have been reduced if their access to basic equipment, such as latex gloves and protective clothing, had been improved. Instead, it was reported that in some cases doctors had to treat patients with their bare hands, increasing their risk of infection.25

On the other hand, President Johnson Sirleaf’s decisive leadership in the situation is highlighted by others, with supporters emphasising that the government acted quickly to understand the scale of the threat posed by the virus, and that the president placed the response high on the priority list of her government. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the Government of Liberia was the first to take the virus seriously and mobilise resources to mount a response, in partnership with both local and external actors.26 A Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) report explains that,

The Liberian government was transparent about Ebola from the beginning and accepted its limitations on how to handle the outbreak … There were also more institutional obstacles and denial in the two other countries at the beginning of the outbreak, but both countries will eventually get to zero cases if the response system remains focused.27

Beyond this, President Johnson Sirleaf was able to coordinate well with international and national actors by creating the Presidential Advisory Committee on Ebola, which acted on behalf of the government in working with other stakeholders to eradicate the virus.28 The government deployed security forces to oversee the closure of all schools in Liberia and to provide surveillance at borders and airports. All government employees, except heads of ministries and agencies, deputies and other essential staff, were placed on mandatory leave and state buildings disinfected. Johnson Sirleaf ‘s administration also advised people to stay away from public places and entertainment centres, and prohibited large public gatherings and demonstrations.29

Overall, Liberia was the first of the three worst-hit West African countries to emerge from the crisis and eradicate Ebola from within its borders. While the emergency is not entirely over, the government must be commended for its responses, as it is clear that its actions were indeed correct as they lowered the death toll over a few months, before finally achieving the total eradication of the virus altogether.

2. The part played by the international community

The regional and international community made concerted efforts to assist the country in tackling and eradicating the disease but measures were, for the most part, viewed as largely slow and ineffective. Actions taken by Liberia include declaring a State of Emergency in November 2014 and launching a National Task Force for Ebola Outbreak Response, a government-led initiative aimed at achieving tangible improvements in outbreak containment measures at community level.

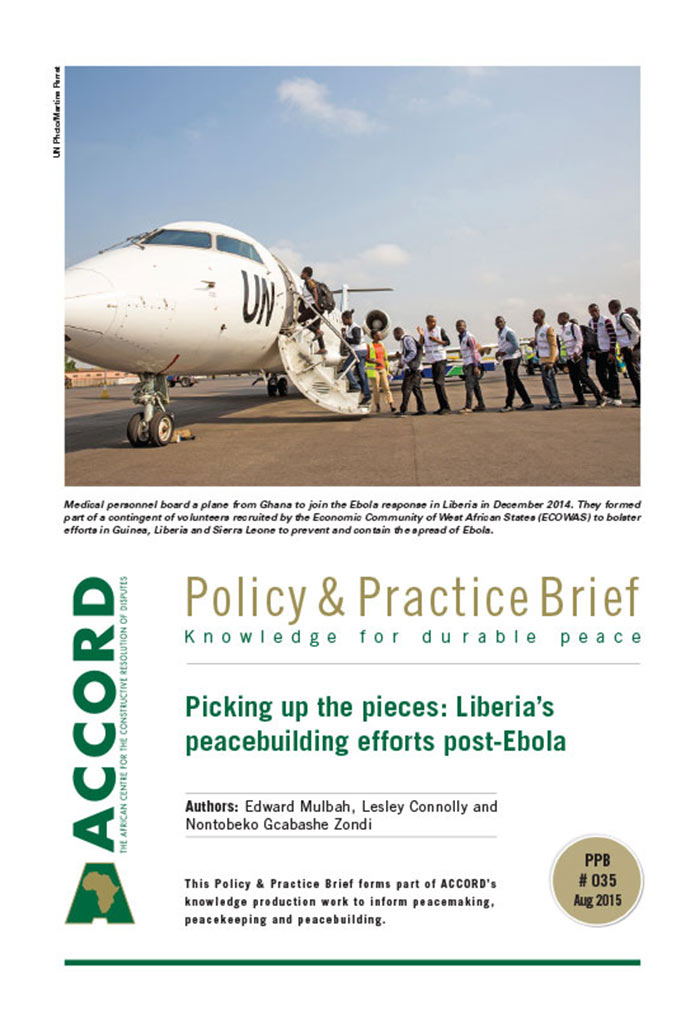

Some African countries, including Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Mali, closed their borders, while Kenya and South Africa, amongst others, stopped flight services to Liberia. The African Union (AU) established the African Union Support to Ebola Outbreak in West Africa (Operation ASEOWA) and sent both military and civilian missions to the affected countries. ECOWAS, in partnership with the African Development Bank (AfDB), provided US$300 000 for responses to the Ebola crises in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.30 Pledges of aid money and food were donated to an estimated one million people living in restricted access areas in Liberia by other stakeholders.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) launched its first ever UN health emergency mission and deployed the United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER). Its role was to support stabilisation and prevent the further spread of the virus in affected and unaffected areas.31 The WHO developed a Strategic Action Plan for Ebola Outbreak Response that included working with Liberia’s minister of health and providing strategic guidance and support.

The US deployed a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) to Liberia, Mali, Guinea and Sierra Leone to lead the overall US response to the emergency. Starting in August 2014, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) worked to increase the number of Ebola clinics and burial teams in West Africa to contain the disease and stop it spreading further. The agency also worked with the UN and local civil society and international partners to bring in more healthcare workers. Further, the US military was deployed to Liberia to provide citizens with critical training in safely caring for patients. The DART significantly expanded the pipeline of medical equipment and critical supplies to the region and supported US public health service efforts to run a field hospital in Liberia to treat health workers who contracted the disease.32 Following closely behind the US, Cuba also offered substantial assistance to the fight against Ebola. The country deployed 460 doctors to West Africa, and sent a further 50 000 healthcare professionals to 66 countries around the world.33 Contributions by both China and India were significant, with China pledging US$35 million to the UN’s main Ebola relief fund and sending close to 200 healthcare personnel to the affected region.34 India disbursed US$12 million to support responses to the epidemic.35

Despite these interventions, some Liberians maintain that the responses came too late and that the ‘decisions and slow response rate [of the international community] resulted in the various socio-economic impacts’ outlined above. Liberians will, therefore, appreciate where the international community and regional bodies provide support to programmes such as reparation, memorialisation and reintegration of Ebola victims, including orphans and survivors, while helping to support initiatives to address trauma, stigmatisation, discrimination and broad outreach and communication around prevention and management of the epidemic.36

3. Community responses

The Civil Society Organisation Ebola Response Taskforce was launched as a national civil society initiative in response to the crisis and comprised a group of CSOs in Liberia. The taskforce’s work included establishing a situation room to buttress government’s efforts. The situation room was primarily employed to analyse the impacts of Ebola on Liberia’s socio-cultural and security situations, as well as to monitor the coordination mechanisms of the government and its partners. The national initiative also aimed to increase citizens’ access to information on Ebola trends in the country, and to advocate for more effective measures to put in place to contain the virus and provide sufficient personal protective equipment, facilities and well-equipped treatment centres.37

Beyond responses by health officials and CSOs, involving traditional structures in monitoring reporting and responding to community concerns (i.e. replacing solid walls at treatment centres with see-through walls to dispel malicious rumours), have been commended as incredibly effective in educating people and helping the situation.38

The coherence and coordination shown between civil society initiatives, health workers, government and international actors should also be acknowledged, particularly for the dedication shown in working together towards the greater goal of eradicating the virus. This coordinated work should continue into efforts to rebuild the society in the post-Ebola era.

Moving forward

As Liberia emerges from the crisis and moves forward, it is important for the international peacebuilding community, the government and civil society actors to work together to address the country’s health, development and peacebuilding challenges, and assist in overarching efforts to develop a strategy to enhance coherence that allows the nation to move forward. There are several key issues to address, starting with rebuilding citizens’ trust and faith in the government. Concerted efforts are needed to foster social cohesion and improve Liberians’ faith in the government and the international community they feel abandoned them, as evidenced by what many believe was a slow response in making aid available. Relationships need to be rebuilt and mindsets transformed. Linked to this, the crisis highlighted inadequacies in the healthcare system and its ability to meet the needs of the people, contributing to the perpetuation of the crisis. It is important to restore Liberian’s trust in their healthcare system and its ability to provide the necessary care and prevent the escalation of future health crises.

Coordinated efforts are needed to ensure the payment of reparations, memorialisation of victims, and reintegration of Ebola survivors and orphans. Within the Strategic Roadmap for National Healing, Peacebuilding and Reconciliation is a component which provides for memorialisation. This can be expanded to include both the memorialisation of Ebola victims as well as those of the civil war. Beyond this, however, it is critical for the government and international community to clearly demonstrate commitment to providing for the basic social needs of the population. Also of importance is drafting an economic recovery and reconstruction plan to assist Liberia in re-launching its economy. This will require rapid financial injection, particularly into agricultural projects that will lead to the creation of jobs. Confidence in investing in Africa decreased as a result of the Ebola crisis, among other factors. As such, international financial institutions may need to develop innovative guarantee instruments to assist the private sector to ‘buy down’ the risk of investing in the affected countries. The international community, working in collaboration with the public and private sector, can facilitate these tasks.

Further, efforts need to be made by those involved to support civic education on issues such as disaster preparedness and management to prevent crises of this magnitude from occurring in the future. There is widespread acknowledgement of the need for an early response system to prevent the outbreak of conflict; this should be expanded to include addressing anything which could cause instability, including health crises. The establishment of early warning and rapid response systems to manage emergencies would thus be a crucial first step.

Overall, for any of these efforts to succeed, capacity strengthening is needed, as is support to improve coordination and coherence of peacebuilding initiatives. Local and international actors should be encouraged to work together to develop the capacities of actors to ensure that a more coordinated approach is taken towards consolidation and recovery, through the building of skills and knowledge, and the provision of tools to address the challenges presently facing the country. Further, inter-governmental organisations, regional economic communities and friendly governments’ support in building strong institutions and resilience, especially at the local level, is needed in efforts to consolidate the fragile peace that exists in Liberia.

Conclusion

On 10 May 2015, the WHO declared Liberia Ebola-free as 42 days had passed since the last victim had died in the country.39 As efforts to renew and refocus the country’s peacebuilding agenda and to move towards stability start to take off, all eyes are on Liberia and how this nation, which is both a post-conflict and fragile state, will recover and consolidate its peace process. With the UNMIL set to officially hand over responsibility for security to the Government of Liberian no later than 30 June 2016,40 and with the presidential election scheduled for 2017, it is imperative that the country consolidates its peacebuilding efforts quickly and moves forward.

Liberia finds itself in a precarious position, trying to address the challenges it was left with at the end of the civil war in 2003 as well as the new fragility exacerbated by the Ebola virus. The country is facing mounting needs which must be addressed to allow the nation to stabilise and make progress on the route to sustainable peace. The government needs to be supported to develop its peacebuilding, health and development sectors, as well as to focus on rebuilding citizens’ and the international community’s trust in the government’s ability to respond effectively to similar emergencies in the future. Liberia is in dire need of investment to improve its economic growth and job creation and, consequently, the cost of living. The social divisions that were and are still evident in communities across the country must be addressed. Reconciliation is vital, and the Strategic Roadmap for National Healing, Peacebuilding and Reconciliation should be re-examined and adapted to respond to the current challenges facing the country.

Efforts by the government, Peacebuilding Office, and UN agencies, including UNMIL, as well as by civil society actors to rebuild the country after the war and to eradicate Ebola from Liberia are commendable and must be recognised. Coherence and coordination initiatives led by the government and the contributions of the international community point to a major commitment to supporting progress in the country and its growth after the serious set-backs occasioned by the epidemic. Liberia is resilient and the country can recover fully from its current fragile state by, among others, ensuring that it is able to retain local and international support, through demonstrations of its own efficiency and good leadership and management.

Going forward, however, the international community needs to recognise that development and peacebuilding go hand-in-hand and that Liberia is a prime example of the need to ensure that after peace has been achieved, development activities are foregrounded, to ensure that resilience is achieved and long-lasting stability maintained. Concerted efforts by local and international actors to work together and develop a coherence strategy to rebuild the country and establish sustainability, resilience and trust among those in Liberia to ensure that the impact of any future crises are less devastating should also be encouraged.

Endnotes

- Liberia’s population as of 2003, when the civil war ended.

- Long, W.J. 2008. Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission: An interim assessment. International Journal of Peace Studies, 13 (2), p. 1.

- The Ebola outbreak in West Africa, which began in March 2014, is the largest and most complex since the virus was first discovered in 1976, resulting in more confirmed cases and deaths than in all other episodes combined.

- A private organisation based in the US.

- This period denotes the full period from the beginning of the country’s first civil war to the end of its second.

- Singh, P. and Connolly, L. 2014. The road to reconciliation: A case study of the Liberian reconciliation roadmap. African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes. Durban, African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes. Available from: <https://accord.org.za/publication/road-to-reconciliation/> [Accessed 7 August 2015].

- Ibid.

- An 18-year development plan crafted by Liberians to give their nation a middle income status by the year 2030.

- These 11 projects address a variety of economic and political challenges facing Liberia. For more information see the Strategic Roadmap for National Peacebuilding, Healing and Reconciliation. Available from:<http://www.lern.ushahidi.com/media/uploads/page/3/Reconciliation%20Roadmap%20Draft%203-W.pdf>

- Singh, P. and Connolly, L. 2014. Op. cit.

- World Health Organization. 2015. World Health Organization situational report 5 August. World Health Organization. Available from: <http://apps.who.int/ebola/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-5-august-2015> [Accessed 7 August 2015].

- World Health Organization. 2015. World Health Organization situational report 6 May. World Health Organization. Available from: <http://apps.who.int/ebola/en/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-6-may-2015> [Accessed 7 August 2015].

- Johnson, S.W. 2014. Liberia’s Ebola pandemic: A case of institutional failure. S-CarNews. Available from: <http://scar.gmu.edu/newsletter-article/liberias-ebola-pandemic-case-of-institutional-failure> [Accessed 7 August 2015].

- Murrey, J. 2014 Why Ebola is a ‘conflict’ issue, a local perspective. Common Ground Blog, 22 August. Available from: <https://www.sfcg.org/why-ebola-is-a-conflict-issue-a-local-perspective/> [Accessed 7 August 2015].

- United Nations. 2014. UN, Liberia assessing food security impact of Ebola outbreak, planning response. United Nations News Centre, 1 October. Available from: <http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=48975#.VXVR0mSqqko> [Accessed 2 August 2015].

- Ibid.

- Songwe, V. 2015. Fighting Ebola: A strategy for action. In: Foresight Africa: Top priorities for the continent in 2015. Washington, Africa Growth Initiative. Available from: <http://dspace.africaportal.org/jspui/bitstream/123456789/34727/1/fighting%20ebola%20songwe.pdf?1> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Democracy Reporting International and The Carter Center. 2012. Strengthening international law to support democratic governance and genuine elections. Democracy Reporting International and The Carter Center. Available from: <http://www.eoeu/library/strengthening-international-law-to-support-democratic-governance-elections.pdf> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- United Nations. 2014. Citing Ebola outbreak’s profound toll on Liberia, top official tells Security Council plague must be stopped in its tracks. United Nations Security Council, 9 September. Available from: <http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11553.doc.htm> [Accessed 16 October 2014].

- World Health Organization. 2015. The Ebola outbreak in Liberia is over. World Health Organization, 9 May. Available from: <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2015/liberia-ends-ebola/en/> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Hinshaw, D. 2014. Ebola virus outbreak tests Liberian president. The Wall Street Journal, 26 August. Available from: <http://www.wsj.com/articles/liberia-struggles-to-contain-ebola-virus-outbreak-1409062213> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Ibid.

- Allison, S. 2015. Think again: Why did Liberia beat Ebola before Guinea or Sierra Leone? Daily Maverick, 19 May. Available from: <http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2015-05-19-think-again-why-did-liberia-beat-ebola-before-guinea-or-sierra-leone/#.VYFJZ1Wqqko> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- MacDougall, C. 2014. Liberia’s Ebola nightmare. Aljazeera America, 2 August. Available from: <http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/8/2/liberia-battles-ebola.html> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Osayande, A. 2014, AfDB, ECOWAS partners to curb Ebola. News24, 23 October. Available from: <http://m.news24.com/Nigeria/World/News/AfDB-ECOWAS-partner-to-curb-Ebola-20141023> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Global Ebola Response. no date. UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response. Global Ebola Response. Available from: <https://ebolaresponse.un.org/un-mission-ebola-emergency-response-unmeer> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- United States Agency for International Development. 2015. Ebola: Get the facts. United States Agency for International Development. Available from: <http://www.usaid.gov/ebola/facts> [Accessed 10 June 2015].

- Sifferlin, A. 2015. Why Cuba is so good at fighting Ebola. Time, 5 November. Available from: <http://time.com/3556670/ebola-cuba/> [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- Hornby, L. and Donnan, S. 2014. China steps up support for fight against Ebola. Financial Times, 10 October. Available from: <http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/fb1b4c06-5042-11e4-9822-00144feab7de.html#axzz3iUzE1kKS> [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- The Indian Express. no date. India to contribute USD12 million to UN to fight Ebola. The Indian Express. Available from: <http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/india-to-contribute-usd-12-million-to-un-to-fight-ebola/> [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- Reflections by Edward Mulbah on 15 April 2015 at a roundtable discussion on Liberia that was organised by the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) and hosted at its headquarters in Durban, South Africa. The event focused on the peacebuilding context in post-Ebola Liberia. Discussions evaluated the effect of the epidemic on the Liberian government in relation to peacebuilding and reconciliation.

- Sendolo, A. 2014. Liberia: CSOs Ebola taskforce opens situation room. The Inquirer Newspaper, 10 October. Available from: <http://allafrica.com/stories/201410070082.html> [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- Allison, S. 2015. Op. cit.

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa – case counts. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 8 August. Available from: <http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html> [Accessed 12 May 2015].

- Front Page Africa. 2015. Liberia’s US$104 million transition plan for life after UNMIL. Front Page Africa, 10 April. Available from: <http://www.frontpageafricaonline.com/index.php/news/4911-us-104-million-transition-plan-for-life-after-unmil> [Accessed 12 June 2015].