The Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC) was created on 22 August 2012, following an agreement between the African Union (AU) and the Republic of Senegal, and was inaugurated on 8 February 2013. The EAC constituted not only a turning point in the fight against impunity for the crimes committed by Hissène Habré’s regime, but also, at a regional level, was the first African initiative against the impunity of serious crimes committed on African territory by African citizens against African populations, whatever the rank they were occupying at the time. The experience of the Special Court for Sierra Leone can be noted, but it should be further noted that this was not a purely African solution (like the EAC), since it was put in place through an agreement between the United Nations (UN) and the Government of Sierra Leone.

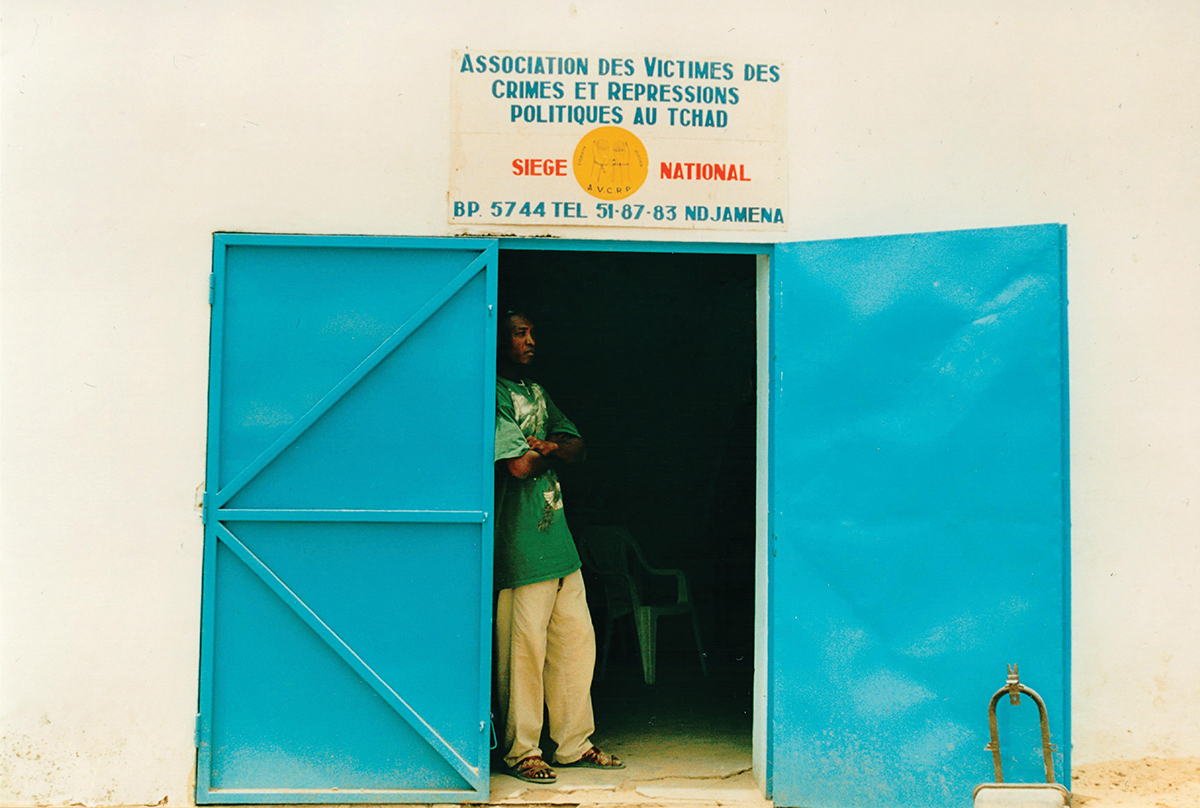

The EAC was created for the prosecution of international crimes committed in the territory of the Republic of Chad during the period from 7 June 1982 to 1 December 1990. These dates correspond to the period during which Habré was in power in Chad. Habré’s presidency was a time of widespread political killing, systematic torture and thousands of arbitrary arrests. Chadians lived under the terror of a political police whose directors reported directly to Habré himself. More than 40 000 people are estimated to have suffered from abuse and torture, and many of them died.1

The creation of the EAC was not easy at all. In fact, the victims of Habré’s regime had to overcome various obstacles before the establishment of a court where they could obtain justice. The Republic of Senegal, where Habré is living since his exile in December 1990 when he was overthrown, has placed several barriers to different proceedings undertaken by victims. Senegal first refused to judge Habré, because the crimes for which he is accused were committed outside its territory. Then, it refused to extradite him to Belgium, where proceedings were opened against him on the basis of this country’s law of universal jurisdiction. Facing this refusal, Belgium asked the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to order Senegal to prosecute or extradite Habré. The ICJ did so, in a landmark verdict delivered on 20 July 2012 in the case of Belgium v. Senegal. The ICJ held that all the state parties to the UN Convention Against Torture (UNCAT), including Senegal and Belgium, have a common interest to ensure that acts of torture are prevented and that their perpetrators do not enjoy impunity. The ICJ went on to state that all the state’s parties “have a legal interest” in the protection of the rights involved, and that these obligations may be defined as “obligations erga omnes partes“, in the sense that each state party has an interest in compliance with them in any given case.2

The ICJ, clearly stating the obligations of the state’s parties under the UNCAT, reaffirmed that these obligations are triggered by the presence of the alleged offender, regardless of their or the victims’ nationality, in its territory. It held that:

The common interest in compliance with the relevant obligations under the Convention against Torture implies the entitlement of each State party to the Convention to make a claim concerning the cessation of an alleged breach by another State party. If a special interest were required for that purpose, in many cases no State would be in the position to make such a claim. It follows that any State party to the Convention may invoke the responsibility of another State party with a view to ascertaining the alleged failure to comply with its obligations erga omnes partes.3

On the basis of this, the ICJ decided that Senegal did indeed have an obligation to prosecute Habré, or extradite him to a state that was capable and willing to prosecute him.

Before this decision, on 24 January 2006 the AU established a Committee of Eminent African Jurists to consider options for Habré’s trial. Based on the committee’s report, on 2 July 2006 the AU asked Senegal to judge Habré “on behalf of Africa”. It is against all this background that Senegal agreed, on 24 July 2012, to the AU’s proposal, which provided for the creation of a special tribunal within the Senegalese court system, composed of African judges appointed by the AU. On 24 August 2012, an agreement was signed to this effect between the two parties.4

The EAC should not only be assessed with focus on Habré’s case, but rather it should be seen in a broader sense as the starting point of an African system of criminal justice, made by Africans for Africans. While awaiting the implementation of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights, such institutions can be seen as peaceful means of settling disputes. This is in line with AU member states’ commitment to promote and protect peace, security and stability on the continent, and to protect human and people’s rights in accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) and other relevant human rights instruments.5

Since the adoption of the charters of the International Military Tribunals (IMT) of Nuremberg and Tokyo, it is well established that there exists what can be referred to as “crimes against peace”.6 Although crimes against peace, as referred to in the IMT charters, are nothing but crimes of aggression, in general, massive and grave human rights and humanitarian law breaches are not only “unimaginable atrocities that deeply shock the conscience of humanity” but are also “crimes [that] threaten the peace, security and well-being of the world”.7 As such, they can be considered in a broader sense as crimes against peace. Therefore, to ensure peace, security and stability in the world and especially in Africa, it is of the utmost importance to fight against impunity and make sure that these crimes “must not go unpunished and that their effective prosecution must be ensured by taking measures at the national level and by enhancing international cooperation“.8 To this effect, steps have to be taken at the African level, in accordance with the norms that exist in the general view of protecting peace and in the specific definition of crimes against peace in Africa.

The Protection of the Right to Peace in Africa

The right to peace and security is clearly stated in Article 23 of the ACHPR in these words: “All peoples shall have the right to national and international peace and security.” Even though this right can be understood in the context of solidarity and friendly relations between states avoiding subversive activities against each other, it is not limited to this. It also means the right of individuals within states to live in peace and security and to be protected from attacks, whether by government or rebel military groups. This is how the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has interpreted this provision in the case of Malawi African Association and others v. Mauritania.9 As such, massive human rights and humanitarian law violations are an infringement to the right of peace and security as defined by the ACHPR.

It is because such crimes are regularly committed in Africa that the AU has the specific mandate to prevent them – or, at least, protect African populations against them. According to Article 3(f) and (h) of its Constitutive Act, the AU has the specific objectives to “promote peace, security, and stability on the continent” and to “promote and protect human and peoples’ rights in accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other relevant human rights instruments”. Thus, the role of the AU in peacebuilding in Africa is directly derived from its Constitutive Act, and indirectly flows from the promotion and protection of rights enshrined in the ACHPR.

In addition, Article 4 provides for the principles that guide the AU in its action. According to Article 4(i), one of the principles is the peaceful co-existence of member states and their right to live in peace and security. This remembers the right of people and individuals to live in peace and security, as provided for by Article 23 of the ACHPR. The other principles are the right of the AU to intervene in a member state in respect of grave circumstances, namely war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity; the right of member states to request intervention from the AU to restore peace and security; the respect for democratic principles, human rights, the rule of law and good governance; respect for the sanctity of human life, condemnation and rejection of impunity and political assassination, acts of terrorism and subversive activities; and condemnation and rejection of unconstitutional changes of governments.

All these principles emphasise the AU’s mission to preserve and consolidate peace, security and stability. Thus, peace can be said to be preserved where effective remedies are taken to fight against grave breaches of human rights and humanitarian law; consolidate democracy, good governance and the rule of law; and fight against impunity of those who have contravened these principles. The AU was then not acting without authority when it signed an agreement with Senegal to try and prosecute Habré for the crimes committed during his regime. However, for the sake of millions of Africans, it should not limit itself to this specific case, but should go beyond this case pursuant to its objectives and principles and, if not create, at least give its existing organs (judicial organs) full criminal jurisdiction over crimes that threaten peace. These crimes must reflect the criminality as it takes place in the African territory, and should not merely be a pale copy of what has already been done at the international level.

The Crimes Targeted

The idea of the “sanctity of human life”, as consecrated in Article 4(o) of the AU Constitutive Act, firmly advocates the the inviolability of human life, protected by the right of a human being for respect of his life and the integrity of his person, as well as the right to have the dignity inherent in a human being respected, as recognised by Articles 4 and 5 of the ACHPR. These rights are themselves protected by the right not to be discriminated and the right to equal protection of the law, as provided for by Articles 3 and 2 of the ACHPR. Read together, it means that all necessary measures have to be taken on African soil to sanction all the potential violations of the “sanctity of human life”. The first step in this regard is the definition of all the crimes that constitute infringement of the “sanctity of human life”, and through this threaten people’s and individuals’ right to live in peace, security and stability.

The Statute of the EAC identifies four crimes that are liable to breach peace and security in Africa. According to Article 4 of the Statute, these are the crime of genocide; crimes against humanity; war crimes; and torture. The procedures undertaken in Chad, Senegal and Belgium against Habré, and the procedure at the ICJ between Belgium and Senegal, were mostly based on the crime of torture. Why has this crime been allowed to stand on its own in the Statute of the EAC? The question is pertinent, because torture is already defined as a war crime [Article 6(g)] or as a crime against humanity [Article 7(b)]. The Statute could have limited itself to providing for these broad categories of crimes and leaving it to the prosecutor to show that Habré committed torture as an element of crime against humanity or war crimes. Or possibly the emphasis on torture here is to highlight the fact that it was the principal mode of responding to political opponents during Habré’s regime. This is not a strong argument.

Since war crimes are necessarily committed during war times, it may be difficult to prosecute Habré on the ground of torture as a war crime. However, crimes against humanity can be committed at any time, during war or outside the context of war. As such, Habré could be prosecuted for torture as a crime against humanity. According to Article 6 of the Statute of the EAC, this crime entails “a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population”. In its report, the National Commission, created in Chad in 1990, inquired into the crimes and misappropriations committed by Habré, his accomplices and/or accessories:

[It] drew up a list of 3 806 individuals – including 26 foreigners – who had either died in detention or had been illegally executed between 1982 and 1990, and made an estimate that the final number could amount to 40 000 dead. It recorded a total number of 54 000 prisoners (including both dead and alive) during the same period. The Commission’s estimate was that the task it had carried out only dealt with 10% of the violations and crimes committed under Habré.10

One can easily draw from this report that, as stated by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in the case of Jean Paul Akayesu,11 Habré did commit torture during his regime, as part of an ‘attack’ on the civilian Chadian population. Because of their dissenting political opinion, several members of this civilian Chadian population were seen by Habré as “enemy population”, according to the terms used by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in the case of Dragan Nikolić.12

Therefore, if Africa were to create its own criminal judicial system, it should first and foremost define – in addition to the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes – other crimes that repeatedly threaten or constitute a breach of the peace, security and stability on the continent. When reading the AU Constitutive Act, it can be seen that except for the crimes listed previously, AU member states express serious concern about unconstitutional changes of governments, which they condemn and reject as a whole [Article 4(p)]. This question is so important that AU member states, “inspired by the objectives and principles enshrined in the Constitutive Act of the African Union, particularly Articles 3 and 4, which emphasizes the significance of good governance, popular participation, the rule of law and human rights,”13 agreed to adopt the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, and whose Article 4(1) calls for state parties to “commit themselves to promote democracy, the principle of the rule of law and human rights”. Article 13 of the ACHPR also strengthens these principles.

On the basis of all this, the fourth crime against peace, security and stability in Africa should be framed as “crimes against democracy and constitutional order”. The elements of these crimes would therefore be:

- unconstitutional changes of government;

- unpredictable changes of constitutions;

- discrimination and persecution based on political opinion;

- fraud and lack of transparency in elections; and

- grave breaches of the principle of effective participation of citizens in democratic and development processes and in governance of public affairs.

To conclude on this point, it is worth mentioning that it is not sufficient to define crimes which infringe on peace and security in Africa. The second step is to put in place institutions, preferably on a permanent basis, that will sanction the perpetrators of those crimes. In this respect, the EAC can operate as a precursor in this direction, and the AU has to build on this experience to achieve the implementation of a permanent African criminal court in the short, mid or long run.

Endnotes

- The Guardian (2015) ‘The Guardian View on Hissène Habré’s Trial: A Major Step Forward for Justice in Africa’, Available at: <http://www.theguardian.com/world/chad> [Accessed 7 November 2015].

- International Court of Justice (2012) ‘Questions Relating to the Obligation to Prosecute or Extradite (Belgium v. Senegal)’, Available at: <http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/144/17064.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2015].

- Ibid.

- Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Senegal and the African Union on the establishment of the Extraordinary African Chambers within the Senegalese judicial system and Statute of the Extraordinary African Chambers within the Senegalese judicial system for the prosecution of international crimes committed on the territory of the Republic of Chad during the period from 7 June 1982 to 1 December 1990.

- Constitutive Act of the African Union, Article 3 (f) and (h).

- Charter of the International Military Tribunal of Nuremberg, Article 6(a), and Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, Article 5(1).

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Preamble, para. 2 and 3.

- Ibid., para. 4.

- In this case, following attacks on Mauritanian villages by Mauritanian public forces and rebel forces, the African Commission held that: “The unprovoked attacks on villages constitute a denial of the right to live in peace and security”. Communications 54/91, 61/91, 98/93, 164–196/97 and 210/98, para. 140.

- International Federation for Human Rights (2015) ‘Chronology of the Hissène Habré Case’, Available at: <https://www.fidh.org/International-Federation-for-Human-Rights/Africa/Chad/hissene-habre-case/> [Accessed 1 October 2015].

- International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1998) The Prosecutor v. Jean Paul Akayesu, Case No. ICTR-96-4-T, para. 205. Jean Paul Akayesu served as mayor of Taba commune from April 1993 until June 1994. As mayor, Akayesu was responsible for performing executive functions and maintaining order in Taba, meaning he had command of the communal police and any gendarmes assigned to the commune. He was subject only to the prefect. He was considered well-liked and intelligent. During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, many Tutsis were killed in Akayesu’s commune, and many others were subjected to violence and other forms of discrimination. Akayesu not only refrained from stopping the killings, but personally supervised the murder of various Tutsis. He also gave a death list to other Hutus, and ordered house-to-house searches to locate Tutsis. He was indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda for genocide, crimes against humanity and violations of Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1948.

- International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (1995) The Prosecutor v. Dragan Nikolić, Case No. IT-94-2-R61, para. 27. The accused, Dragan Nikolić, is a former Serbian commander of the Sušica camp near Vlasenica in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was arrested in Bosnia and Herzegovina by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-led Stabilization Force (SFOR) and taken to The Hague in The Netherlands for trial. He was indicted by the ICTY in November 1994 for crimes against humanity and war crimes.

- Preamble of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, para. 1.