In 2014, the Republic of Tanzania granted citizenship to more than 160 000 Burundian refugees.1 Most of them had fled the country during the 1972 massacres and the 1993–2005 civil war. Tanzania’s decision to grant naturalisation certificates to Burundian refugees was commended by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other international organisations.2 It was hoped that the decision would encourage other countries in the Great Lakes Region to grant citizenship to refugees born in their territories, including those who had held refugee status for several years.

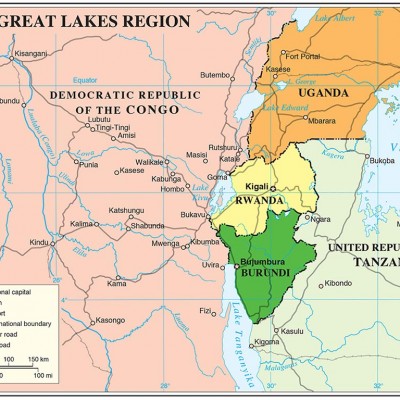

The Great Lakes is one of the regions in Africa that has been affected by a high number of refugee-related problems. Conflicts, famine and violence have pushed millions of people away from their places of origin. For several decades, the region has also been engulfed in violent intrastate and proxy interstate conflicts. The Rwandan genocide in 1994, the Burundi and South Sudan civil wars, and the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are still ongoing deadly conflicts that have caused an irregular migration of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the region. Scholars have identified the Great Lakes Region as consisting of not only the DRC, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania, but also including South Sudan, Somalia, Sudan, Angola, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Zambia, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Central African Republic (CAR) and Republic of Congo3 – all of which share the ravages and fallout of these intractable conflicts.

Under the 1969 Organisation of African Unity (now the African Union) Convention, a refugee is any person who, reasonably fearing persecution on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership to a social group or political opinions, is outside the country of which they have nationality/citizenship status but cannot, or will not, because of this fear, claim its protection.4 The 2009 African Union (AU) Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa, identified as the Kampala Convention, defined IDPs as persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalised violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognised state border.5

During the Rwandan genocide, more than two million people fearing retribution, including Hutu civilian militias who were accused of having committed the genocide, fled to the neighbouring countries of Burundi, Tanzania and the DRC. The Hutu militias’ plan to regain control of power was the reason for the Rwandan authorities to pursue them and attack their rear bases in the DRC. This conflict paved the way for the creation of a new Congolese rebel group, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire, which attacked and toppled former president Mobutu Sese Seko, culminating in the two Congo Wars in 1996 and 1998. In November 1996, 640 000 refugees left their camps6 in Goma (DRC) and returned to Rwanda after their camps were attacked by the Rwandan Defence Force. However, more than 200 000 refugees remained in Goma while several others moved westward, deeper into the DRC. The Interahamwe, one of the youth militias involved in the Rwandan genocide, fled into the Congolese forests. These militias came together with the former soldiers of the Armed Forces of Rwanda, and founded a rebel group called the Army for the Liberation of Rwanda, which would become the Democratic Liberation Forces of Rwanda (FDLR).

During the same period (1993–2009), an armed conflict broke out in neighbouring Burundi. The civil war was triggered by the assassination of Melchior Ndadaye, the first democratically elected Hutu president. The war caused the killing of thousands of Burundian citizens, Hutu and Tutsi alike. Relative peace returned to most of the country in 2005, when one of the former rebel groups, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy – Forces for the Defense of Democracy, became the ruling party. The Arusha Peace Agreement, signed in 2000 by most of the parties in the conflict, paved the way for an end to the civil war. As a result, thousands of refugees who had fled to neighbouring countries after the assassination of President Ndadaye were able to return.

The current Burundian political crisis, which erupted due to disputes relating to the incumbent president’s decision to continue his presidency against the provisions of the constitution limiting the presidential terms, has again forced thousands of refugees into Tanzania, Rwanda and the DRC. Owing to continuing instability and despite the calls by various international bodies for people to return home, most refugees remain reluctant to return, fearing a potential return to sustained armed conflict.7

The eastern region of the DRC (North Kivu and South Kivu provinces) has been unstable with regard to security. Armed groups, such as the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), continue to kill men and women in the city of Beni. These attacks have pushed thousands of people out and away from their villages. Kenya harbours the world’s largest refugee camp complex in Dadaab. Kenya hosts more than 330 000 Somali refugees in Dadaab,8 over 42 000 Somali refugees and some 270 000 South Sudanese, who have taken refuge in the Kakuma refugee camp to escape from civil war.9 There are currently more than two million refugees and IDPs in the Great Lakes Region. Table 1 indicates the number of refugees and IDPs, and shows that countries in the region will always be affected when conflicts flare up. Peacebuilding programmes need to be pursued in earnest in this region to address the causes of these huge human migrations.

| Table 1: 2015 UNHCR Subregional Operations Profile10 | |||

| Countries | Refugees from | Refugees to | IDPs |

| Burundi | 232 881 | 52 936 | 78 948 |

| DRC | 516 770 | 159 440 | 2 658 000 |

| Kenya | 8 556 | 580 460 | 0 |

| Rwanda | 79 411 | 85 020 | 0 |

| Uganda | 7 191 | 560 170 | 0 |

| Tanzania | 857 | 296 000 | 0 |

The presence of refugees has been a major security issue for all the countries in the region, while some highlight the added advantages that come with the movements of these refugee groups into the various neighbouring countries. Some reports indicate that certain refugees join armed groups or terrorist organisations operating in the countries they have settled in, while other refugees may also bring skills and knowledge into the host country, where they will begin to participate in development projects that contribute to the local economy.

The large number of refugees and IDPs poses immense challenges to peacebuilding processes within the region. These huge numbers of refugee movements impact on peace and security, and cause citizenship challenges and cross-border conflicts among different ethnic groups, among a plethora of other problems. As a result of the ever-growing numbers of refugees and IDPs, competition for land and economic resources has often been the trigger for conflict.

The countries in the Great Lakes Region are not only concerned about these huge numbers of refugees as a threat in the region. There are also other concerns relating to the refugees’ impact on the environment, healthcare and cultural identity. However, as stipulated in the 2006 International Conference of the Great Lakes Region Pact on Security, Stability and Development, the region’s focus should be more on democracy, humanitarian and social welfare, economic development and security.11 These latter protocols in general focus on the challenges to peacebuilding processes in the region.

Security Challenges

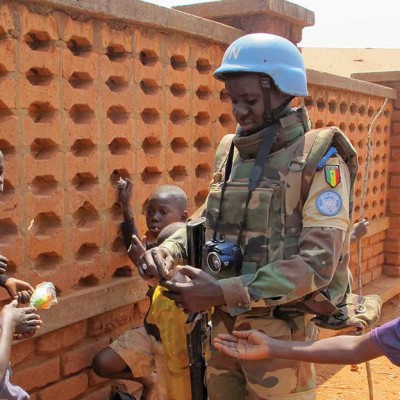

The refugee and IDPs crisis has been an issue of concern with regard to peace and security. When refugees are settled in camps, there are security challenges for both the refugees’ country of origin and the host countries. After the Rwanda genocide in 1994, Hutu extremists used refugee camps in the DRC to recruit combatants for cross-border attacks to destabilise Rwanda. In 2014, to appease Rwandan authorities, hundreds of FDLR combatants were moved to a camp in Kisangani, thousands of kilometres away from the borders. The process was carried out under the supervision of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO).12

Refugee camps may also be used by terrorist organisations to recruit and attack host countries. In recent years, the Kenyan government accused Al-Shabaab, a Somali rebel group, of conducting attacks in the country. Officials have claimed that it is from the Dadaab refugee camps, inside Kenyan territory, that Al-Shabaab plans its acts of terror – such as the 2015 attacks at Garissa University and the 2013 Westgate Mall attack – and that this camp must be shut down.13 Though 5 000 refugees have voluntarily returned to Somalia from the Dadaab camps in the past year, security and socio-economic conditions in many parts of Somalia are still not conducive for large-scale returns.14

Insecurity can exist within the camp itself. Despite the fact that the Lusenda refugee camp in the DRC is far from the border, as per the UNHCR policies, refugees report that they are not safe. A Burundian man was recently taken into custody by the DRC police after a woman recognised him in the camp as an Imbonerakure15 member from her community back in Burundi. The Imbonerakure is a youth political wing of the ruling party, reported to have committed violent crimes and accused of intimidating political opponents in Burundi. After being questioned, the man said that he was forced to join the group and he wanted asylum in the DRC. Refugees also report that the camp may be infiltrated by members of both Burundi security forces and the opposition. This puts them in a situation where they cannot speak freely for or against either party, due to fear of retaliation.16

In Burundi, a number of high officials who held dissenting opinions about the incumbent president’s decision to run for a third term in 2015 went into exile in Rwanda.17 There is a high likelihood that they will remain politically active, even though they are refugees. When refugees remain active while in a foreign land, their sympathies can lead to them offering support to armed groups with similar ideas. There have been several reports of non-state armed groups recruiting Burundian refugees in camps in Rwanda to join Burundian rebel groups.18

Burundian top government officials have accused the Rwandan government of tacitly aiding their enemies – that is, former ruling party members who sought refuge in Rwanda.19 This alleged support to enemies, if true, contravenes the convention governing the specific aspects of refugee problems in Africa, which stipulates: “Signatory States undertake to prohibit refugees residing in their respective territories from attacking any State Member of the AU, by any activity likely to cause tension between Member States, and in particular by use of arms, through the press, or by radio.”20

It is a challenge for camp authorities and humanitarian organisations to differentiate refugees from rebels, terrorists or infiltrators in the camp. Within communities or camps, rebels or terrorists live like ordinary refugees. Last year, Kenya threatened to expel thousands of Somali refugees living in camps to curb terrorism perpetrated inside its territory.21 This challenge has posed a serious security threat for the region in terms of weapons smuggling and trafficking contraband, leading to a variety of transborder crimes.

Another political crisis that could cause refugee numbers to swell further may come from Rwanda and the DRC, where leaders are trying to amend their constitutions to enable them to run for a third term in office. The amendment of the constitution was approved in Rwanda through a referendum. A constitutional change in both countries could have a negative effect on the refugee crisis, as well as on political and economic stability in the region. People will likely protest and that could then lead to more violence and foreign assistance, or investments may be cut.

Socio-economic Challenges

The countries in the Great Lakes Region are among the poorest in the world, with most of them emerging from protracted conflicts that may reignite if the root causes are not resolved. Countries in the region have to promote economic development and job creation within the framework of good governance and human security to alleviate poverty, which is one of the main causes of instability.

Due to political crisis, Burundi is currently under threat to be excluded from the African Growth and Opportunity Act.22 The United States government is reviewing Burundi’s eligibility to the group in matters of human rights, following the disputed elections in July 2015, and the German government has suspended any cooperation with the Burundi regime, although assistance programmes that serve the population will continue through cooperation with non-state organisations.23 Deducing from such developments, it becomes easier to speculate that if the crises were to escalate further, donor countries could freeze their direct investments. This would negatively impact the economy of those countries affected, and the region as a whole.

The consolidation of peace in this conflict-prone region is linked to issues of democracy, respect of human rights and the rule of law. Without these factors, more conflicts will erupt and lead to more people seeking refuge in neighbouring countries. Once a conflict has been successfully resolved, refugees can return home without any fear of being persecuted, but their concern might be to arrive and find their land(s) or properties occupied.

Land and its significance is frequently an underlying cause of widespread violence, as well as a critical element in peacebuilding and economic reconstruction in post-conflict situations.24 Consequently, if the access to, control and usage of land is not well managed, it can undermine the consolidation of peace in a post-conflict region. Some countries in the region have land institutions and policies that are in place as mechanisms for the management of land-related conflict. In Burundi and the DRC, land issues have been one of the causes that have triggered conflicts in rural communities; and Rwanda has put in place a legislation, as part of the Arusha Agreement, for refugees to repossess their properties upon return.25 This has been an effective way to prevent land-based ethnic conflicts.

It should be noted that, in host and original home countries, refugees and IDPs also positively impact the economy. When they flee to neighbouring countries and when they return home, they bring new skills and become part of the active labour force. Tutsi refugees, who were in refugee camps in Uganda, returned to Rwanda after the genocide in 1994 to contribute to the rebuilding of a sustainable economy in the country.

Conclusion

In May 2013, Jim Yong Kim, World Bank president, and Ban-Ki Moon, UN Secretary General, launched a socio-economic initiative for the Great Lakes Region. The objective of this regional programme, which is valued at US$1 billion, is to facilitate the rebuilding of infrastructure that was destroyed during conflicts, and implement a long-term strategy to assist and reduce refugee and IDP numbers.26

The reduction of refugee and IDP numbers can be achieved through one of three solutions: voluntary repatriation, local integration and resettlement. A resettlement programme could be adopted by rich or stable African countries to receive high numbers of refugees by granting them permanent residencies, but it may also promote an increase in the number of ‘bogus refugees’. The latter factor remains a bottleneck with regard to resettlement in a third country, especially in the Western part of the globe. It is hard to identify a bogus refugee in a camp – they could be economic migrants who are in pursuit of a better life and social benefits, and not refugees.27 Even when the security situation has improved, some refugees are reluctant to participate in a voluntary repatriation programme, in the hope that they will be resettled in a Western country.

Whether positive or negative, challenges due to an influx of refugees and IDPs will affect peacebuilding processes in the region. Some countries in the region are still fragile states with strong leaders, and lack democratic institutions. There is a need to transform these fragile states into stable states that will protect civilians and prevent protracted conflicts and an expansion of violence in the region.

The general elections in CAR in December 2015, security in the DRC and the Burundi peace talks could end the violence in the region and encourage the return of many refugees and IDPs back to their communities and countries. Regional peacebuilding actors need to design a comprehensive and sustained strategy to consolidate peace in the Great Lakes Region, by addressing the root causes of the conflicts and building the capacity of local and national actors to prevent, manage and peacefully transform conflicts.28

Endnotes

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2014a) ‘Tanzania Grants Citizenship to 162,000 Burundian Refugees in Historic Decision’, Available at: <http://www.unhcr.org/5441246f6.html> [Accessed 1 September 2015].

- UNHCR (2015a) ‘2015 UNHCR Country Operations Profile – United Republic of Tanzania’, Available at: <http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e45c736.html> [Accessed 5 December 2015].

- Omeje, K. and Hepner, T.R. (eds) (2013) Conflict and Peacebuilding in the African Great Lakes Region. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 3.

- Cimade, Inodep and Mink (1986) Africa’s Refugee Crisis. What’s to be Done? London: Zed Books, p. 112.

- African Union (AU) (2009) ‘African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention)’, Available at: <http://www.au.int/en/sites/default/files/AFRICAN_UNION_CONVENTION_FOR_THE_PROTECTION_AND_ASSISTANCE_OF_INTERNALLY_DISPLACED_PERSONS_IN_AFRICA_(KAMPALA_CONVENTION).pdf> [Accessed 9 November 2015].

- Adelman, H. (2003) The Use and Abuse of Refugees in Zaire. In: Stedman, S.J. and Tanner, F. (eds) Refugee Manipulation: War, Politics, and the Abuse of Human Suffering. Washington: Brookings Institution Press, p. 100.

- Fondation Chirezi (FOCHI) (2015) Interview with the author on 4 August. Uvira, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- UNHCR (2015b) ‘2015 UNHCR Country Operations Profile – Kenya’, Available at: <http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e483a16.html> [Accessed 17 October 2015].

- UNHCR (2015c) ‘UNHCR 2015 Planning Figures for Uganda’, Available at: <http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e483c06&submit=GO> [Accessed 9 November 2015].

- UNHCR (2014b) ‘2015 UNHCR Subregional Operations Profile – Central Africa and the Great Lakes as at December 2014’, Available at: <http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e45a6c6.html#> [Accessed 18 January 2016].

- Fleshman, M. (2007) ‘Pledging Peace at Great Lakes Summit’, Available at: <http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2007/pledging-peace-great-lakes-summit> [Accessed 20 October 2015].

- Radio Okapi (2015) ‘Saïd Djinnit encourage les FDLR regroupés í Kisangani í rentrer au Rwanda’, Radio Okapi, 9 July, Available at: <http://www.radiookapi.net/actualite/2015/07/09/djinnit-encourage-les-fdlr-regroupes-kisangani-rentrer-au-rwanda> [Accessed 21 September 2015].

- Allison, S. (2015) ‘World’s Largest Refugee Camp Scapegoated in Wake of Garissa Attack’, The Guardian, 14 April, Available at: <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/14/kenya-garissa-dadaab-scapegoat-al-shabaab> [Accessed 17 October 2015].

- Kelley, K.J. (2015) ‘Somalis Leaving Kenya, but Mass Return Not Possible, UN Says’, Africa Review, 17 October, Available at: <http://www.africareview.com/News/Somalis-leaving-Kenya-but-mass-return-not-possible-UN-says/-/979180/2918546/-/8u00sbz/-/index.html> [Accessed 19 October 2015].

- Buchanan, E. (2015) ‘Burundi: Who are the Feared Imbonerakure Youth?’, International Business Times, 3 June, Available at: <https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/burundi-who-are-feared-imbonerakure-youth-1504301> [Accessed 17 October 2015].

- National Commission of Refugees (2015) Interview with the author on 3 August. Uvira, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- eNCA (2015) ‘Burundi Journalists, Activists Seek Refuge in Rwanda’, eNCA, 27 June, Available at: <https://www.enca.com/africa/burundi-journalists-activists-seek-refuge-rwanda> [Accessed 16 September 2015].

- Boyce, M. and Vigaud-Walsh, F. (2015) ‘Asylum Betrayed: Recruitment of Burundian Refugees in Rwanda’, Available at: <http://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2015/12/14/rwanda> [Accessed 15 December 2015].

- Santora, M. (2015) ‘Fragile Burundi Casts a Wary Eye on Rwanda’, The New York Times, 3 August, Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/04/world/africa/after-unrest-a-fragile-burundi-views-rwanda-with-suspicion.html?_r=0> [Accessed 16 September 2015].

- UNHCR (2015b) op. cit.

- Ecofin Agency (2015) ‘U.S. Envisage Exclusion of Burundi from AGOA’, Available at: <http://www.agenceecofin.com/law/2008-31509-u-s-envisage-exclusion-of-burundi-from-agoa> [Accessed 1 September 2015].

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) (n.d.) ‘Burundi’, Available at: <http://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/314.html> [Accessed 1 September 2015].

- Theron, J. (2009) Resolving Land Disputes in Burundi. Conflict Trends, 2009(1), p. 4, Available at: <https://accord.org.za/publication/conflict-trends-2009-1/> [Accessed 15 September 2015].

- International Conflict Research Institute (INCORE) (n.d.) ‘Arusha Peace Agreement’, Available at: <http://www.incore.ulst.ac.uk/services/cds/agreements/pdf/rwan1.pdf> [Accessed 5 December 2015]. Article 4 of the Protocol Agreement on the Repatriation of Rwandese Refugees and the Resettlement of Displaced Persons stipulates: “The right to property is a fundamental right for all the people of Rwanda. All refugees shall therefore have the right to repossess their property on return. The two parties recommend, however, that in order to promote social harmony and national reconciliation, refugees who left the country more than 10 years ago should not reclaim their properties, which might have been occupied by other people. The Government shall compensate them by putting land at their disposal and shall help them to resettle. As for estates which have been occupied by the Government, the returnee shall have the right for an equitable compensation by the Government.”

- Kalikat, Y. (2015) Assistance des populations affectées par les déplacés. La Banque Mondiale mobilise 50 millions de dollars supplémentaires pour la RDC. Forum des As, 21 December, p. 8.

- Fondation Chirezi (FOCHI) (2015) op.cit.

- Irene Limo and James Machakaire are thanked for their input on this article.