Introduction

Since the early 1990s, the focus of the United Nations’ (UN) peacemaking and peacekeeping efforts has largely been directed to Africa. In the beginning, these efforts were symbolic of the rest of the world coming to the aid of Africa. Over the last 20 years, however, Africa has developed significant capacity of its own, and today Africans make up the largest proportion of the UN’s civilian, police and military peace operation staff. As of March 2015, approximately 60% of the UN’s 5 200 international civilian peace operations staff and about 80% of its 11 600 local staff are African. In addition, Africa has now become the largest regional contributor of police and soldiers to UN peace operations, and contributes approximately 48% of the UN’s 106 000 uniformed peacekeepers.1

Over the same period, there has been a significant increase in the peace operations capacity of the African Union (AU). Over 40 000 uniformed and civilian personnel were mandated to serve in AU peace operations in 2013 (or approximately 60 000, if the joint AU-UN hybrid mission in Darfur is taken into account as well).2 Since then, the AU missions in Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR) have been transferred to the UN and, as of March 2015, the AU is responsible for the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) – the world’s largest peace operation, with over 22 000 uniformed personnel. It also provides strategic headquarters functions for the Multi-National Joint Task Force operation against Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin, and the AU regional cooperation initiative for the elimination of the Lord’s Resistance Army (RCI-LRA).

This is the story of how the Training for Peace (TfP) in Africa Programme contributed to building Africa’s peacekeeping capacity. In 1995, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) established the TfP Programme. In 2015, TfP has thus been in existence for 20 years, which is a remarkably long period for any programme of this nature. Over these two decades, Norway invested approximately US$50 million through TfP in African peacekeeping capacity building.3 During the course of 2015, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs will decide whether to continue the TfP Programme – and, if so, in what form.

Regardless if TfP continues beyond 2015, it is worthwhile to reflect on the contribution it has made over the past 20 years to peacekeeping capacity building in Africa, and to try and identify the lessons the TfP experience might offer for other projects that may have similar objectives in the peace and security field. I have been part of the TfP story since 1997, when I joined ACCORD to manage its TfP Programme, so I am not in a position to offer an objective or independent assessment. TfP has been regularly evaluated, with the most recent independent external evaluation, commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), published in 2014.4 Rather, I will try to offer some self-reflection and try to capture some of the essence of the TfP experience from an insider’s perspective.

Context and Founding

In the early 1990s, UN peacekeeping was controversial because of its failures in Rwanda, Somalia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. In response, the major powers decided to invest in building Africa’s capacity, so that it would take more responsibility for managing African conflicts. Around the same time, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) – and later the AU – decided to establish its own internal conflict management mechanisms and peace support operations (PSO) capacity.

It is in this context that the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, together with NUPI, ACCORD and the ISS, established the TfP Programme. Its objective was to contribute to peacekeeping capacity building in Africa. Initially, the focus was on southern Africa, but from the outset TfP was closely involved in the larger African project. For instance, the OAU invited ACCORD and the ISS to provide expert advice to the 1997 African Chiefs of Staff meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, which was tasked to lay the foundation for an African approach to peace operations. The TfP partners remained closely involved in African peacekeeping, and have helped to shape the creation and subsequent development of the African Standby Force (ASF).

TfP also supported UN peacekeeping in Africa over the 20-year period, and most recently provided support and substantive input to both the UN High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations, and to the development of the AU common position on the UN panel on peace operations. Among others, TfP helped the UN panel on peace operations to organise its African consultations in Addis Ababa in February 2015.

North-South-South Partnership

When reflecting on TfP’s characteristics, a few features come to mind. TfP is an interesting partnership between entities in the North and South. In the North, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs initiated the TfP idea and provided the funding. The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs worked closely with NUPI, which provided peacekeeping expertise, as well as with the Norwegian armed forces and police. At that point in time, Norway was a significant repository of knowledge on UN peacekeeping policy, whereas the African contribution was often limited to the provision of troops. NUPI has been closely engaged in research and supporting UN peacekeeping since its inception, and the Norwegian armed forces and police were significant contributors to UN peacekeeping operations.

This, however, changed over the lifetime of the project. The African partners developed significant peacekeeping expertise of their own. Over time, the balance shifted and, in more recent years, TfP has become a vehicle for South-North knowledge-sharing on African peacekeeping. For example, the Norwegian police, in addition to the courses it conducts in Africa on its own or in support of the ISS and Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC), also invites African instructors to support its UN Police courses in Norway. In the South, the two initial African think tanks, ACCORD and the ISS, were joined by the KAIPTC in Ghana in 2003, and for a short period between 2010 and 2013, the African Civilian Response Capacity for Peace Support Operations (AFDEM) was also part of the TfP family.

The African partners took the lead on TfP’s interaction with African countries, the regional economic communities/regional mechanisms (RECs/RMs) and the AU. This is unique compared to other international efforts to support African capacity in the peace and security field, in that most other efforts are direct government to government or donor to AU and RECs/RMs partnerships. The relationship between civil society and the state in Africa is often full of tension and mistrust, but the TfP experience has been different. The African think tanks and training centres have been able to develop constructive relationships with African countries, RECs/RMs and the AU. This is remarkable if one considers that the project deals with the sensitive area of security, and involves close cooperation and interaction with the military and police.

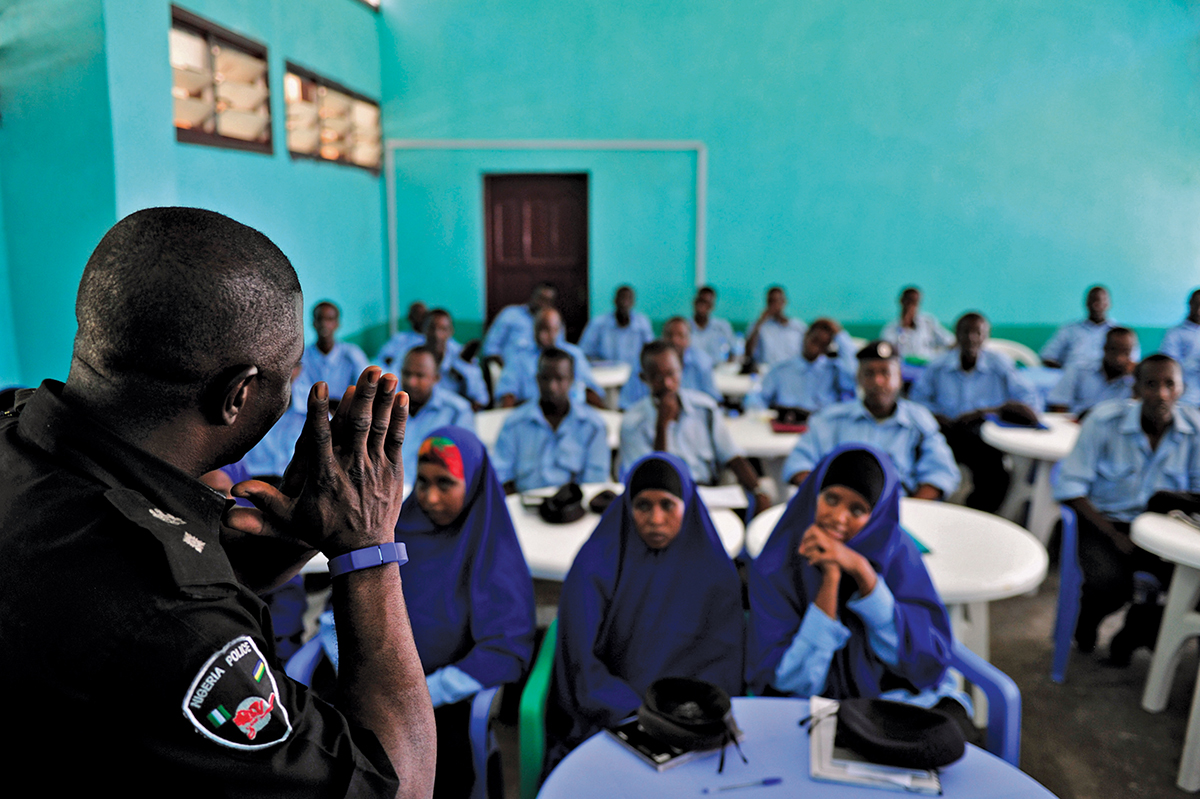

The Civilian and Police Dimensions of African Peace Operations

Another characteristic feature of TfP is its focus on the civilian and police dimensions of peacekeeping. The United States, the United Kingdom, France and several other countries have supported the development of Africa’s military peacekeeping capacity, both bilaterally as well as via the ASF. Whilst there are thus several initiatives underway focused on military capacity, TfP was initially the only programme to focus on the civilian and police dimensions. Later, Canada became more involved in police capacity building, and Germany and Japan also started to support civilian capacities. However, TfP has been the AU and RECs/RMs’ most consistent partner on the civilian and police dimensions over this 20-year period.

The expertise TfP developed on the civilian and police dimensions of peace operations in Africa enabled its partners to contribute significantly to UN reform initiatives, such as the Civilian Capacity initiative and the UN Police Strategic Guidance Framework initiative. TfP was also catalytic in the generation of several other successful spin-offs. It helped to establish the African Peace Support Trainers Association (APSTA), which today is the official AU-recognised network of peacekeeping training centres in Africa, and also serves as the African chapter of the International Association of Peacekeeping Training Centres (IAPTC). TfP’s efforts to assist the AU to hire civilian staff resulted in a project, with Norwegian support administered by the Norwegian Refugee Council, which generates a number of African civilian experts for the AU Commission and African PSOs, forming the core expertise on civilian matters and planning at AU Headquarters today. In addition, Norway directly supports a number of posts within the AU Commission, including three police positions, and since 2008 the Norwegian police has seconded a police adviser to the East African Standby Force headquarters in Nairobi.

Research, Policy Development and Training

The TfP Programme combines research, policy development and training. It uses research to develop new knowledge on UN and African peacekeeping experiences, working closely with the UN and AU to gain access to field missions for empirical research. The research informs both TfP’s policy development and training interventions. TfP works with the AU to support the development of the ASF, and especially its civilian and police frameworks, as well as policies in areas such as gender, conduct and discipline and the protection of civilians.

Similarly, TfP works with the UN to support the development of its gender, protection of civilian, local peacebuilding and civil affairs policies and guidelines. The research and policy development work, in turn, supports the development of training manuals and teaching materials, such as the UN Civil Affairs Handbook, the UN protection of civilians training package, and the UN Police course. This work also informs the training courses that TfP partners provide for African countries, the RECs/RMs, the AU and the UN.

Perhaps most interesting is the shift to in-mission training over the latter years of the project. The training component of the TfP project evolved significantly over the past 20 years as it continuously aspired to be more relevant, results-orientated and cost-effective. In the first phase, TfP conducted generic peacekeeping training in all Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries. The target group was military, police and civilians who might be interested in serving in AU or African peace operations. In the second phase, TfP conducted generic pre-deployment courses for civilian and police officers, as well as mission-specific pre-deployment courses for military and police officers. Whilst pre-deployment remained an important aspect of TfP training, in the third and fourth phases the partners shifted a significant portion of TfP’s civilian and police training to in-mission training. The TfP partners also provided training to the AU missions in Burundi, Sudan and Somalia, including induction training for the civilian component of AMISOM.

Whilst only a small portion of those trained in the early years ended up serving in peace operations, in the latter years most of the people trained – including all of those trained in-mission – served in peace operations. This shift was informed, in part, by the research TfP itself conducted into how many people who received training ended up being deployed. The research concluded that as TfP has little influence over how people get selected to deploy, TfP could best achieve its aims by contributing to the capacity and skills of those already deployed.5

At the same time, TfP invested in developing the civilian and police dimensions of the ASF, including its civilian standby roster, so that it could also contribute to ensuring that the AU and RECs/RMs have a ready supply of civilian and police peacekeepers to deploy when needed.6 Since 2000, ACCORD, on behalf of TfP, entered into a memorandum of understanding with AFDEM, and in 2010 AFDEM became a TfP partner, in an attempt to also constructively engage with and develop Africa’s civilian standby rostering capacity. When the AU – partly as a result of the work undertaken by TfP – embarked on a process of establishing an AU roster for African peace operations, TfP shifted its support to that effort.

Strategic Coherence and Programmatic Flexibility

The TfP Programme has benefited from a management structure that has ensured strategic coherence, whilst allowing for programmatic flexibility. Over the past 20 years the TfP Programme evolved through four phases, but its core identity and focus remains coherently centred on helping to build the capacity of the civilian and police dimensions of African peacekeeping operations through research, policy development and training. This is due to the consistent application of the principles governing the TfP partnership, a coherent strategic management approach and the stability of the partnership and its members.

The principles that govern the TfP Programme are African ownership, decentralisation and relevance. The programme is guided by the needs of the AU, the RECs/RMs, African member states and the UN. The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs trusts the partners to maintain a close working relationship with the UN, AU, RECs/RMs and African member states. This ensures that it is their needs and priorities that drive the future direction of the programme. The longevity of the programme has allowed meaningful relationships to be developed, and partners were able to build trust and credibility that increased over time as more joint initiatives were successfully completed. The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs also established an International Advisory Board (IAB) in 2000, to assist in ensuring that the TfP Programme was strategically informed. Further credibility and feedback was added to the strategic management of the programme through IAB members’ networks.7

The management structure of the TfP Programme changed with each phase. In general, it is highly decentralised in that the partners are responsible for their own programme design and implementation. Their programming has to be in line with the overall strategic direction provided by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the IAB and partners in a cooperative strategic guidance process, but the partners have great leeway to give operational and programmatic meaning to how the strategic goals of the project are to be pursued. The annual meetings and periodic independent evaluations further help to generate feedback and to stimulate adaptation. This approach enables the TfP Programme to stay strategically coherent, whilst at the same time being highly relevant, innovative and adaptive to the changing needs of the AU, RECs/RMs, African member states and the UN. One of the assessments of the programme by the IAB and independent evaluators revealed that the TfP Programme has managed to remain consistently ahead of the curve. The TfP Programme has been at the forefront of several major policy developments, including gender; women, peace and security; protection of civilians; civil-military coordination and mission integration; and the emergence of the civilian and police dimensions of peace operations.

The TfP Programme is also under continuous pressure to generate results that are relevant for the AU, RECs/RMs, African member states and the UN. Results are assessed by periodic external reviews and evaluations, as well as by the partners themselves, with guidance from the IAB. It has also been the practice to invite, in addition to the standing members of the IAB, representatives of the AU and UN to the annual strategic review sessions of the IAB. Over time, TfP became increasingly results-orientated and, in its fourth phase, the partners developed a fairly detailed results matrix. The focus on results and relevance for AU and UN peace operations contributed to the drive within TfP to be highly responsive to the changing needs of the AU and UN. In several cases, TfP partners helped to identify and innovate new AU and UN policy initiatives, such as the civilian and police policy frameworks of the ASF.

A best practice that emerged from TfP’s own iterative, adaptive experience is to identify a policy process that is important for the AU or the UN, and which matches the objectives of the programme – for example, the civilian and police dimensions of African peace operations, the UN’s Civilian Capacity initiative, the UN Police Strategic Guidance Framework or the emerging protection of civilians doctrine. TfP partners then work closely with the AU and UN for several years on these policy processes, using the TfP Programme’s research, policy development and training programme interventions. This enables TfP partners to develop relevant expertise and build meaningful relationships with their counterparts in the AU and the UN. It also means that the research undertaken is policy-relevant and can feed into the development of training material, thus creating a virtuous cycle around a policy stream that is judged to be important by the AU and the UN.

The longevity of the programme and the stability among the partners means that there is a strong sense of institutional continuity. As one can imagine, over 20 years a considerable number of people spent time with TfP. Most moved on, but some people remained associated with the programme over most of its lifetime, including the directors of ACCORD and the ISS and, since 2003, the head of the research unit at the KAIPTC. This means that the directors own the institutional memory and narrative of the history of the TfP. Several staff members left TfP to join the AU, UN or other relevant institutions and, in this way, the TfP Programme contributed to generating staff and building the capacity of the AU and UN. The success and impact of TfP is thus in part due to the network of individuals who have been engaged with, or were associated with, TfP.

One aspect that has perhaps been neglected in the various evaluations is the degree to which TfP has contributed to building the capacity of the TfP partners themselves. This effect can be seen in the degree to which the TfP partners are today recognised as important knowledge brokers by the AU, RECs/RMs, African member states and the UN. TfP was an important part of the developmental history of each of the partners, and also contributed to the development of African think tanks with expertise in the peacekeeping area. A closely related aspect is the degree to which TfP contributed to the TfP partners having access to and credibility with the AU and the UN. The TfP partners are seen today as critically important partners for the AU and the UN when it comes to developing new policies, as sources of credible research and as training providers. The partners have access to AU and UN missions to undertake empirical field research and are invited to conduct pre-deployment, orientation and in-mission training for AU and UN missions. The partners have also been closely engaged in the development of the AU and UN’s policy process related to, among others, the development of the protection of civilian guidelines for the UN and the AU, new police doctrines for both institutions, the UN Civilian Capacities initiative, the UN Police Strategic Guidance Framework, the strategic assessment of AMISOM in 2012, the review of the ASF in 2013, and providing support for the UN High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations in 2015, to name a few examples.

Conclusion

The TfP Programme is itself an interesting case study in terms of how a government such as Norway can work in partnership with think tanks like NUPI, ACCORD, the ISS and the KAIPTC, supported by the Norwegian police. The TfP Programme is a good example of a North-South-South cooperative partnership to support the AU, RECs/RMs, African member states and the UN. The programme is thus also an example of how state and non-state actors, from the North and South, can work together to make a meaningful contribution to the development of African and UN peacekeeping capacities.

In addition, TfP is an example of how African civil society organisations are working closely and constructively with the AU, RECs/RMs and African member states, even in the sensitive security arena. It is also telling that TfP’s management model has been one that combined strategic coherence with programmatic flexibility, and that this model has generated flexible, responsive and innovative programming. Looking back over the years, one can track how TfP has evolved and adapted, based on the feedback that has been generated by its own monitoring and management processes, or with the help of the IAB and the independent external evaluations.

Over the past 20 years, Africa has developed considerable peacekeeping capacity, as reflected both in the increased role it is playing in UN peacekeeping operations and in the AU’s actual mission record. All the independent external evaluations over the years found that the TfP Programme made a significant and meaningful contribution to this development.

Endnotes

- In comparison, South East Asian countries together contribute approximately 30% of the UN’s uniformed peacekeepers. Six of the top 10 UN troop-contributing countries are from Africa, with Ethiopia now the largest contributor to peace operations in the world if one takes both its UN (7690) and AU (4045) contributions into account. All UN statistics are based on the figures provided by the UN as of 31 March 2015, as available at: <http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/factsheet.shtml>.

- In 2013, the AU managed three peace support missions simultaneously: AMISOM, the African Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA) and the African Support Mission in the Central African Republic (MISCA). The author has estimated the numbers based on AU press statements and Lotze, Walter (2013) ‘Strengthening African Peace Support Operations’, Available at: <http://bit.ly/RzPSOn>. [Accessed 12 May 2014].

- Norad (2015) Building Blocks for Peace: An Evaluation of the TfP Programme, p. 13.

- Ibid.

- Solli, Audun, De Carvalho, Benjamin, De Coning, Cedric and Pedersen, Mikkel (2009) Bottlenecks to Deployment? The Challenges of Deploying Civilian Personnel to Peace Operations. Security in Practice 3/2009. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

- De Coning, Cedric and Kasumba, Yvonne (eds) (2010) The Civilian Dimension of the African Standby Force. Durban: African Union and ACCORD.

- The members of the IAB over the years included, among others: General (rtd) Martin Luther Agwai, Dr Jose Victor da Silva Angelo, Dr Francis Deng, Comfort Ero, Professor Ibrahim Gambari, Jean-Marie Guéhenno, Ambassador Monica Juma, Dr Funmi Olonisakin, Professor Ramesh Thakur and Sir Marrack Goulding.