Introduction

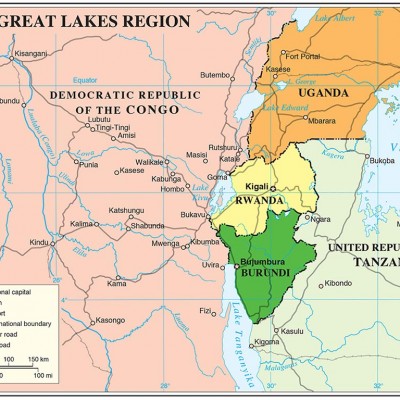

Since they obtained their independence from their colonial masters, the countries that now make up what is commonly referred to as the Great Lakes Region have experienced conflicts and internal wars, leading to loss of life and property. Before the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) was established (prior to the Dar es Salaam Declaration, in 2002), those countries included Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Burundi. In 2004, the number of countries increased to 12 to include Sudan, Zambia, Angola, Central African Republic (CAR), South Sudan and the Republic of Congo.

The countries in this region share the common problem of constant crises and entwined, ongoing conflicts. The Pact on Security, Stability and Development of the ICGLR contains five Programmes of Action and 33 Protocols – and governments and civil society in the region, with the support of the international community, are expected to find lasting solutions to the volatile situation through the Pact’s implementation. The Regional Programme of Action for Good Governance and Democracy captures and describes the situation in these words:

These last decades (1999–2004) the Great Lakes Region has been the theatre of deep and repetitive crises. Bad governance, policies of exclusion and of structural adjustment, constant violence of fundamental human rights… are all factors having contributed to the instability in the region. In the countries directly affected by conflicts and social political crises, the situation has been exacerbated by the destruction of economic and social infrastructure, paralysis or malfunctioning of the key public services, economic slump, increase of military budgets, aggravation of poverty, the HIV/AIDS pandemic, decrease of foreign aid and investments, etc.1

This situation was made worse by the existence of non-democratic regimes, especially in the DRC (under Mobutu Seso Seko) and CAR (under Jean-Bédel Bokassa). Under such regimes, security forces marginalised non-governmental entities such as civil society organisations (CSOs). However, through the determination of the people of the region, the struggle for democracy and good governance persevered.

Early Efforts to Stabilise the Region

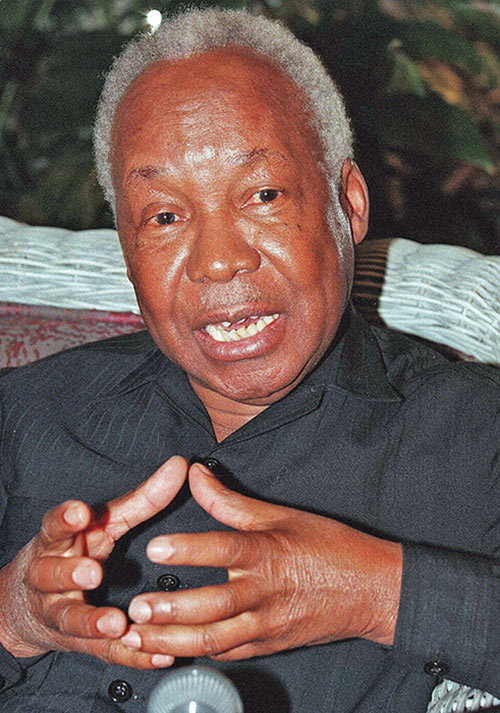

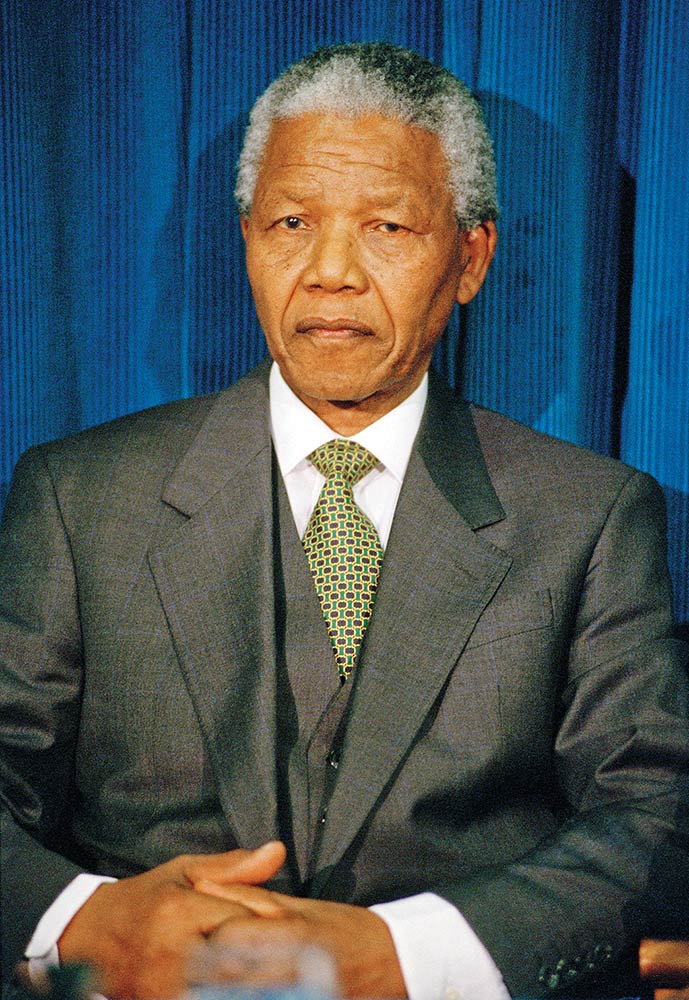

During early efforts towards peacebuilding, conflict management and resolution in the Great Lakes Region (prior to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda), the government of Tanzania – under the leadership of President Ali Hassan Mwinyi and assisted by Ambassador Ammy Mpungwe – attempted to help Rwanda resolve its political instability and crisis. Many CSOs were also involved, and played a major role. In Burundi, retired president Julius Nyerere, using his newly created non-governmental organisation (NGO) The Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation, was appointed by the United Nations (UN)/African Union (AU) to act as an independent facilitator to that country’s conflict. He began work in 1998, bringing together most – if not all – parties to the Burundi conflict. It was a very difficult task, needing much diplomacy and patience in dealing with people, nations and governments. Nyerere died in October 1999 before a peace and reconciliation agreement was brokered. Retired president Nelson Mandela of South Africa took over the next and last phase of the peace process. He succeeded in getting Burundi to accept and sign a peace agreement following a long process of negotiations – and sometimes the use of coercive tactics. CSOs, especially those including women, played a significant role – after they secured their participation in the peace talks and negotiations. Indeed, it was a long process to get the men already involved in negotiations to include women, who were seen to be divided and loyal to the government, the army, parliament or political parties. The UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) played a major role in mobilising women in Burundi, even helping them include their issues in the draft agreement.

Prior to the talks in Rwanda and Burundi, the situation in the DRC had grown from bad to worse. The genocide in Rwanda had produced many refugees, who joined those who had fled earlier to the DRC. According to the government of Rwanda, the UN and AU, these refugees were a source of instability – not only in the DRC (especially eastern DRC) and Rwanda, but also in the region generally. Many refugees in Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi and, to a smaller extent, Zambia, came from the DRC. While initially invited and tolerated, these refugees were eventually disliked or even hated by the citizens of the host countries, especially when they became involved in criminal acts and destroyed the environment. Efforts by the governments of the countries concerned, the UN and the AU – and even bilaterally between these states and foreign governments – did not end the conflict or the loss of property, nor overcome the suspicion between and among countries and people in the region.

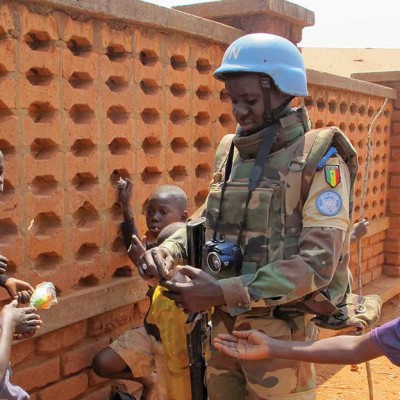

Escalation of the Situation and United Nations–African Union Interventions

The UN (since 1994), the Organisation of Africa Unity (since 1995) and later the AU had, on many occasions, expressed concern about the volatile situation in the Great Lakes Region. In December 1999, the UN Security Council document S/1999/1296 brought attention to the need to deal with the conflicts and potentially explosive situation in the Great Lakes Region. It was also in 2000 that the government of Uganda, through the support of President Yoweri Museveni, extended substantial financial support to the Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation, which organised the first-ever International Symposium on the Consolidation of Regional Solidarity. It was this initiative that qualified the Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation to be appointed by the Joint UN/AU Secretariat as the institution to coordinate civil society input into and during the consultations under the ICGLR.

The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region

It can be said that formal, sustainable efforts towards civil society-government cooperation in consolidation of the regional and national peace and reconciliation agenda were unleashed and consolidated in an inclusive consultative process involving 11 countries of the Great Lakes Region. In its evolution, dialogue, discussions, debates, research and ultimate formulations and establishment, the consultative process that resulted in the ICGLR had, as its principal objectives, inclusiveness, ownership and partnership. The stakeholders of the process and the ICGLR were:

- the 12 member states (Angola, Burundi, CAR, DRC, Kenya, Rwanda, Republic of Congo, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia) and six co-opted countries (Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Namibia, Ethiopia and Egypt);

- governments and civil society;

- the private sector;

- youth;

- women;

- the AU and the UN, as key international institutions;

- the Group of Friends and Special Envoys (co-chaired by Canada and the Netherlands), which offered substantial diplomatic, political, technical and financial contributions and support; and

- regional economic communities: the East Africa Community (EAC), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and so on.

At the end of the all-inclusive consultative process involving governments and society, two key documents were adopted and signed by the region’s heads of state and government: the Dar es Salaam Declaration on Peace, Security, Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region and the Pact on Security, Stability and Development for the Great Lakes Region. For both governments and civil society, these two documents provide the agreed-upon framework within which the four main Regional Programmes of Action (sometimes referred to as ‘Themes’), the 33 Priority Projects and 10 Protocols will be implemented, under the supervision and monitoring of the Regional Follow-Up Mechanism. It is important to emphasise that this framework, and the contents of the work agenda for the region, are supported by civil society in the region. It is a unique regional initiative through a genuine partnership to identify, analyse and synthesise the problems and challenges of security and development, and agree on a way forward in solving them together. This is indeed a real area for even further dialogue and research on strategies for peacebuilding.

The two documents are the key working tools of the ICGLR. Both are clearly defined in legal language so that they are binding to the governments of member states and people, including CSOs, who are expected to use them.

The Dar es Salaam Declaration on Peace, Security, Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region was adopted and signed at the First Summit of the Conference in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on 20 November 2004. The Declaration presented a statement, with the intention of addressing the root causes of intractable conflicts and constraints to development in a regional and innovative approach.2 It has a vision “to transfer the Great Lakes Region into a space of sustainable peace and security for states and peoples, political and social stability, shared growth and development, a space of cooperation based on convergent strategies and policies driven by common destiny”.3 It also includes four Priority Policy options and guiding principles, a Follow-up Mechanism and final provisions.

The heads of state and government convened in Nairobi in 2006 to sign the Pact on Security, Stability and Development in the Great Lakes Region. The Pact serves as a legal framework and an agenda of the ICGLR, with the aim of creating the conditions for security, stability and development between member states.4 The Pact included the Dar es Salaam Declaration, Programmes of Action and 10 Protocols.5

The Role of Regional Civil Society Organisations and the Regional Civil Society Forum

The Regional Civil Society Forum (RCSF) is a consultative mechanism aimed at, inter alia, deepening democratic principles in the Great Lakes Region through the development of appropriate strategies, and the facilitation of engagements and interactions between civil society actors from various countries in the region. RCSF structures are composed of elected national fora coordination committees and bureaus that elect a Regional Coordination Committee and Bureau led by a chairperson. From July 2014, the RCSF supported by different partners including the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC) and the Nairobi Peace Initiative (NPI)-Africa through the Great Lakes Project initiated a long process of establishing national civil society fora in 12 ICGLR Member States in order to revitalise the Regional Civil Society leadership. At the end of the process national civil society fora elections were organised in the DRC, Zambia, Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan and CAR, thus enabling the RCSF leadership to convene a second General Assembly in Dar es Salaam from 7-9 March 2016. The main objective of the General Assembly was to set up a more coherent and coordinated CSO structure at national and regional levels with the aim of strengthening the General Assembly’s voice in relation to interactions with national government, inter-governmental mechanisms (mainly the ICGLR), and other inter-governmental organisations such as the EAC and UN. The General Assembly also created opportunity to renew effective involvement of civil society stakeholders in the implementation of the Pact on Security, Stability and Development and the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework.

CSOs have always played a major role in promoting democracy, resolving conflicts and participating in peacebuilding processes in the region. This has involved first living with and working under oppressive colonial regimes before independence, and second, working with and under national regimes of different perceptions and characteristics – including many that are not democratic, and therefore do not necessarily respect their citizens and are not ready to observe the human rights principles and requirements of social justice.

Within the ICGLR, CSOs are recognised as important and key stakeholders. In the spirit of inclusiveness and ownership, ICGLR CSOs played a major role as partners in the development and production of the Dar es Salaam Declaration and the Pact on Security, Stability and Development.

In the Dar es Salaam Declaration, CSOs are recognised in paragraph 33 and are assigned the role to participate in the consolidation of democracy and good governance, particularly through the promotion of good governance at local levels, and the emergence of independent and responsible media. In paragraph 76, they are mandated to assist the Regional International Committee to prepare selected concrete, achievable and measurable draft Protocols and Programmes of Action, together with specific short-term, medium-term and long-term objectives.6 Through these assignments, CSOs worked – and still work – very closely with the governments of member states.

On the basis of the Pact, CSOs participate in the meetings of the summit, the inter-ministerial meetings, and the regional coordinators’ meetings. They make their statements in these meetings, relating to their own issues or in support of key declarations by heads of state. They also have the responsibility of understanding and implementing the Pact, especially the Democracy and Good Governance Programme of Action.

Through the Regional Civil Society Forum and in close collaboration with other regional fora – women, youth, parliament and the recently established Private Sector Forum – CSOs have been assigned to implement a project: the Regional Civil Society Forum Project 2.5.4. Its main objective is to facilitate CSOs that are playing a determining role in peacebuilding and consolidation of the democratisation process, as well as in long term socio-economic development.

The Regional Civil Society Forum, operating as an umbrella organisation for all CSOs in the region including at national grassroots level, offers a unique opportunity for civil society to build capacity in many fields, and effectively and efficiently collaborate at national, regional or even international levels, including the UN, the AU and other regional economic community organisations. CSOs have a big responsibility, in collaboration with their governments, to ensure that ‘deficiencies’ in the region, at national and regional level, are eliminated. Civil society is aware of these deficiencies, as recognised and defined in the Dar es Salaam Declaration:

The Dar es Salaam Declaration recognizes that accumulated deficiencies in the area of governance and the failure of democratization processes are the main factors causing the violent socio-political conflicts in the region. In fact, the most significant facts of poor governance, such as massive violations of human rights, exclusion and marginalization policies, impunity of crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, disparities between men and women, and the use of violence to serve political purposes constitute the main factors causing endemic conflicts in the Great Lakes Region. In the same way, political systems in effect are still characterized and dominated by the institutionalization of non-democratic management methods, namely the absence of political diversity and of a consensus on the constitutional principles, the non-separation of legislative and judicial powers and their control by the executive power, and the manipulation of the judicial power and security services by the executive power. The socio-political crises the Great Lakes region is going through has also been exacerbated by issues of economic management, namely the appropriation of power by the Executive, the non-adherence to the principles of transparency and integrity in resource management and decision-making, the aggravation of corrupt practices and the illegal exploitation of natural resources.7

Tackling these deficiencies of the past, which are still in effect today, is the joint responsibility of the people – through CSOs in the region, and their governments. Civil society and governments share joint accountability in this broad field of responsibility. They are partners, sharing a common stakeholders’ vision for peace, security, stability and development in the Great Lakes Region.

The structure of the ICGLR includes its objectives; its three principles of ownership, inclusiveness and partnership; its vision and mission; its broadly defined agenda, covering the key areas of peace and security, democracy and good governance, economic development and regional integration, humanitarian and social issues, and other cross-cutting issues; and the well-established Follow-Up Mechanism, which involves governments, CSOs and the UN/AU. Ample opportunity for effective, efficient and productive cooperation between governments and CSOs is made available through the ICGLR Pact. The agenda for cooperation and involvement is not a temporary one: it is permanent. It is based on broad policy options, specific projects and activities to be implemented within the legal framework of the Pact. The potential definitely exists for greater and increased scope for government–civil society work and cooperation for peace, security, stability and development in the Great Lakes Region.

Endnotes

- Regional Civil Society Forum (2005) International Conference on the Great Lakes Region: Regional Programme of Action for Good Governance and Democracy. Project 2.5.4, p. 1.

- International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) (n.d.) ‘Background’, Available at: <http://www.icglr.org/index.php/en/background> [Accessed February 2016].

- ICGLR (2004) ‘Dar-Es-Salaam Declaration on Peace, Security, Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region’. International Conference on Peace, Security, Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region: First Summit of Heads of State and Government, Dar es Salaam, 19–20 November, Available at: <http://www.icglr.org/images/Dar_Es_Salaam_Declaration_on_Peace_Security_Democracy_and_Development.pdf> [Accessed February 2016].

- ICGLR (n.d.) ‘The Pact’, Available at: <http://www.icglr.org/index.php/en/the-pact> [Accessed February 2016].

- ICGLR (2012) ‘The Pact on Security, Stability and Development for the Great Lakes Region’, Available at: <http://www.icglr.org/images/Pact%20ICGLR%20Amended%2020122.pdf> [Accessed February 2016].

- ICGLR (2004) op. cit.

- Ibid.