Dr Robert Senath Esuruku, formerly senior lecturer in the Institute of Ethics and Development Studies at the Uganda Martyrs University, Kampala, is Head of Research in the Uganda-Great Lakes Programme of International Alert.

Abstract

Northern Uganda is undeniably a safer place today compared to five years ago. The relative peace in the region has enabled the majority of former Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) to return to their home areas and begin to rebuild their lives. However, inadequate access to basic services along with unemployment, social dislocation, growing land disputes and inadequate conflict prevention measures present a grave challenge in the region. In order to facilitate the resettlement process, the Government of Uganda has formulated a comprehensive development framework, the Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) for northern Uganda, as a strategy to eradicate poverty and improve the welfare of the populace in the region. This was followed by the resettlement programme launched by the Office of the Prime Minister which has contributed to the rehabilitation and construction of new social service infrastructure to support the livelihoods of the returnees. However, the implementation of the PRDP has fallen short of the envisioned peace, recovery and development in northern Uganda. Conceptual and capacity problems pose a serious challenge to the implementation of the plan. The paper concludes that the PRDP is ill-equipped to comprehensively address the over two decades of deep-seated human anguish, devastation and psychosocial trauma caused by the civil war. It lacks the mechanism to institute social justice through non-discriminatory and equitable accountability of the state and non-state parties for women, men and children in the region. The paper then makes some proposals for healthier implementation of the plan.

1. Introduction

After more than two decades of civil war in northern Uganda, the Government of Uganda (GoU) has formulated a comprehensive development framework, the Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP), as a strategy to eradicate poverty and improve the welfare of the populace in northern Uganda. PRDP is a stabilisation plan which has disaggregated northern Uganda from national sector plans and forms the framework for post-conflict recovery and development intervention. The targets of the PRDP include: consolidation of state authority, strengthening of the rule of law and access to justice, rebuilding and empowerment of communities, peacebuilding and reconciliation, and revitalisation of local communities (GoU 2007). Within the framework of the PRDP, development partners are invited to implement specific development programmes in the region.

The PRDP is based on the premise that effective peacebuilding, recovery and development strategies in northern Uganda require an in-depth understanding of the different armed conflicts which have very grossly affected women, men and their children in many ways. It was designed to propagate community reconciliation and mitigate conflicts as a basis for sustainable development in the region. It is hoped that communities would identify conflict mitigation measures to overcome the legacy of violence and address its underlying causes. The development interventions would then flow out of processes of conflict management by providing former combatants, abductees and victims of violence with livelihood opportunities and secure sources of income from labour and contracts for community infrastructure projects (GoU 2007). The plan also has a monitoring framework to track the progress of development investments to ensure that the targets set by the government are met.

This paper traces and discusses the historical roots of the civil conflict in northern Uganda, its impact in the region, the transition to relative peace, the need for sustainable peace and development and then makes an evaluation of the implementation of the PRDP. Lastly, the paper makes recommendations for better implementation of the plan.

2. Background

2.1 The roots and results of the conflict in northern Uganda

The origin of the civil conflict in northern Uganda can be traced to the deeply rooted ethnic mistrust perpetrated by the colonialists (Kasozi 1994; Latigo 2008; Tripp 2010). The British colonial administration recruited the people of northern Uganda into the armed forces while people from the other regions of the country were mainly employed to work as civil servants. This created a division between people of the other regions of the country who were becoming more developed and the population of the northern region who remained poor and only relied on cattle-keeping as the main source of their livelihood (Gersony 1997; Mamdani 1999). This ethnic and socio-economic divide was exacerbated by political and religious divisions; and since independence in 1962, Uganda’s successive undemocratic governments instigated the war in northern Uganda. The two decades of civil conflict in northern Uganda between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) began in 1986 in the Acholi sub-region. The two warring parties signed cessation to hostilities in 2006.

Social services including agriculture, education and healthcare systems were severely looted and wrecked and many professional employees deserted the region. The earlier attempts by the government to rebuild the region through development programmes such as Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF) were driven by elite socio-economic and political interests and succumbed to massive corruption (Hickey 2003). Although the social fun approach has the advantage of devolving responsibility to the community and protecting those responsible for project implementation from undue political influence, the availability of substantial resources for development purposes was an attractive source of political patronage in a region long deprived of such resources. While the objective of NUSAF was to prioritise the most vulnerable groups and areas, politicians keen to re-establish their legitimacy in the region often used the programme as a footstool for advancing their political ambitions.

The destruction of the region’s economic base and the breakdown in social cohesion have been strongly felt by communities. At the root of this conflict lie issues of inequality and exclusion from state mechanisms and development opportunities, which have marginalised a large proportion of vulnerable groups in northern Uganda. Explanations for the conflict are complex and intertwined and include Uganda’s colonial history, a tradition of political mobilisation along ethnic and regional lines since Independence and the LRA’s religious and identity driven agenda (Allen 2006; Doom and Vlassenroot 1999). Insecurity in the Karamoja sub-region, partly rooted in the proliferation of small arms and problematic disarmament programmes, has hampered the administration of central government services resulting in a chronic breakdown of law and order as well as underdevelopment in northern Uganda (UNDP 2008).

The impact of the conflicts in the entire North has been phenomenal. While the national average of Ugandans living in absolute poverty declined from 38,8% in 2002/3 to 31,1% in 2005/6, poverty levels in northern Uganda increased from 2,9 million in 2002/3 to 3,3 million in 2005/6. Statistics show that nearly one third of the chronically poor in Uganda come from the northern region alone (UBOS 2006).

The Human Development Indices (HDIs) and Human Poverty Indices (HPIs) demonstrate that northern Uganda is lagging behind the rest of the country in terms of regional and district-specific breakdowns. While the national HDI had improved from 0,488 in 2003 to 0,581 in 2006, there were regional imbalances that were skewed against the northern region. The Central region for instance scored the highest HDI of 0,650, followed by the Eastern region with 0,586 and the Western region with 0,564, while the northern region tailed with 0,478 (UNDP 2007).

Furthermore, while the national annual income per capita is estimated at UGX 570 000 (approximately USD 320), the figure for the northern region stands at a paltry UGX 153 000 which is about 27% of the national average. Although at national level, absolute poverty fell from 56% in 1992 to 31,1% in 2006, 61% of the residents in northern Uganda have hitherto remained poor. Similarly, while Uganda’s national infant mortality rate stands at 76 per 1000 live births, the average rate for the north is a hefty 106 per 1000 live births (UNHS 2003). Similarly, the North had the highest HPI of 30,7% as compared with the Central, Western and Eastern regions’ percentages of 20,19, 20,56 and 27,11 respectively (UNDP 2007).

In Acholi, Lango, parts of Teso and West Nile, the immediate effects of the armed conflicts were loss of life, massive destruction of property and breakdown of the social, economic and other infrastructure, but also massive population displacement into Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps. By September 2006, there were 1,3 million IDPs in Acholi sub-region alone (Amuru, Gulu, Kitgum and Pader) – a number equivalent to over 98% of the estimated population of the sub-region. By the end of 2006, there were 251 IDP camps in the entire northern Uganda, some with a population of over 60 000 IDPs and a density of as high as 1 700 persons per hectare. By January 2007, the number of IDPs in northern Uganda numbered more than 1,8 million people (UNHR 2010).

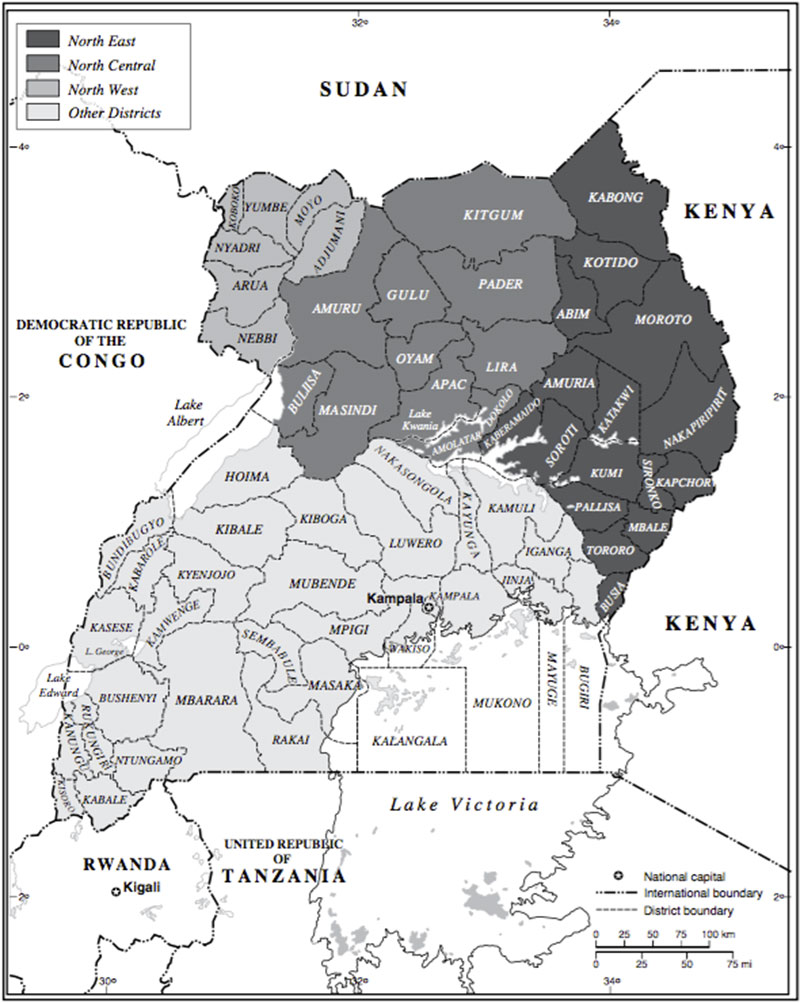

Figure 1: Map of northern Uganda

In Karamoja and neighbouring districts, the armed conflicts associated with cattle raids have increasingly undermined the ability of households to cope with the harsh physical conditions, which increased their vulnerability to food insecurity. Inter-clan and inter-tribal armed cattle raids in Karamoja have also resulted in insecurity, death and low development, much as in the war areas. Many people in IDP camps in Teso and some parts of Lango and Acholi were displaced by the cattle rustling which had prevailed in these areas for nearly 20 years (UNDP 2008).

2.2 Transition from war to relative peace

The negotiations between the Government of Uganda and the LRA, which begun on 14 July 2006 in the South Sudan capital of Juba, have resulted in relative calm in northern Uganda. The signing of a Cessation of Hostilities (CoH) Agreement on 26 August 2006 led to the 29 June 2007 Principles of Accountability and Reconciliation and the final disposal of all items of the negotiation agenda. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) had not been signed. This has in part been attributed to the impasse around the International Criminal Court (ICC) indictments on some of the LRA leaders. Nonetheless, the relative calm in the region has resulted in large numbers of IDPs moving back to their homes. The IDPs were first placed in transit camps to prepare them to return to their original homes.1

However, the current return and settlement of the former IDPs are affected by several factors, including concerns about security, availability of requisite tools for bush clearing, land cultivation and planting materials, and inaccessible roads due to non-maintenance. While there was less congestion in return areas, basic social services such as primary healthcare services, safe water, education, nutrition, protection and shelter are seriously lacking. The over 20 years of exposure to armed conflicts and life in encampment have changed not only lifestyles but more significantly social values which increased the potential for domestic violence. Most of the families returning to pre-displacement sites are broken families headed by divorcees, widows/widowers or other single parents, and many child-headed households. The returnees are facing significant problems accessing land in areas of return. During encampment, most men, due to frustration and redundancy, became accustomed to consuming a lot of alcohol and doing very little work (Pham et al. 2005). The burden of looking after the homes has been that of the women. There are also problems resettling the elderly and disabled persons.

After the LRA guns fell silent, armed thugs who operated under their shadows emerged as the leading cause of terror for IDPs returning to their homes. Different criminal gangs continue to terrorise communities in Amuru, Gulu, Kitgum and Pader districts. Hence, the need for an effective Police Force cannot be over-emphasised. Although the strength of the Police Force has grown from 27 000 in 2006/7 to 48 000 by July 2007, there is still a manpower deficit in the entire northern Uganda (UNDP 2008).

The performance of the Justice, Law and Order sector is also affected by the extremely slow processes of trial for suspects, which undermine the confidence in the justice system. By June 2007, 4 000 of the 32 000 inmates countrywide were in war-torn northern Uganda. The judiciary and public prosecution departments are still weak despite nationwide efforts to improve the performance of these institutions. There are also challenges related to Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD). Recent assessments, however, show that the threat from mines within the war-affected districts is very low (UNDP 2008).

2.3 Attempts to address the need for sustainable peace and development

Northern Uganda to date has a large number of national and international actors providing humanitarian, recovery and development support to war-affected communities. Since the early 90s, the Government of Uganda with donor support has implemented a number of programmes to improve local infrastructure and livelihoods of the war-ravaged communities in northern Uganda. In response to the challenges experienced by the communities in the conflict-affected districts, the Ugandan government put into action a number of measures aimed at enhancing the protection of the civilian population and bringing the region to normalcy. As part of its response to pillar 5 of the Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP), security and conflict resolution, the government developed a comprehensive Internal Displaced Peoples Policy, the Emergency Humanitarian Action Plan (EHAP) and other programmes.

The earliest development programme implemented in the region was the Northern Uganda Reconstruction Programme (NURP-1) with support from the International Development Association (IDA). It was designed to upgrade the infrastructure in the region through the construction of roads and the provision of water supplies, health facilities and schools. In the West Nile sub-region, a demand-driven programme called Community Action Plan (CAP), funded by the Netherlands government, was implemented. Initially CAP was part of the NURP-1 before it became an independent development programme.

In 2002, the Ugandan Government designed a 5-year Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF) development programme funded by the World Bank. The goal of NUSAF was to help local communities in by then 18 districts of northern Uganda that have been ravaged by conflict. This money was given directly to members of the community so they could invest in infrastructure and training for long-term development. NUSAF was a community-driven development programme in which local communities could identify, plan and implement sub-projects geared to improving local infrastructure, promoting livelihood opportunities and resolving conflict.

Other development programmes implemented in the northern region before the PRDP are the Northern Uganda Rehabilitation Programme (NUREP) and the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Plan (KIDDP). These two development programmes later were incorporated into the PRDP. NUREP, which is a European Union-funded programme, is geared to strengthening the self-reliance and protection of the local population in northern Uganda, rehabilitating the social infrastructure and improving the capacity of Ugandan stakeholders to respond to conflicts and disasters. The KIDDP, on the other hand, has the overall goal of contributing to human security and promoting conditions for recovery and development in Karamoja by dealing with the problem of small arms and light weapons.

To support the return and reintegration of the communities, UNDP has designed an Area Based Integrated Development Programme (ABID) for northern Uganda to restore and strengthen the capacities of communities and authorities for sustained recovery, reconciliation and peacebuilding with a view to achieving sustainable development. The primary beneficiaries from the interventions include the most vulnerable such as the elderly, HIV/AIDS victims, widows, child-headed households and people previously abducted by the LRA. To ensure successful implementation of the ABID, UNDP is working closely with the Government of Uganda and the local authorities in six districts in northern Uganda. In addition UNDP has entered into agreements with the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) to implement the livelihood component of the programme. The United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) and the United Nations Development Fund for Women commonly known as UNIFEM are expected to support the implementation of the programme.

3. The Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) for Northern Uganda

3.1 Objectives and programmes

The PRDP is a three-year Government of Uganda plan for the recovery and development of northern Uganda, which currently covers 55 districts and 9 municipalities in northern Uganda. The overall goal of the PRDP is stabilisation in order to regain and consolidate peace and lay the foundations for recovery and development in the region. PRDP was initially conceived as a ‘master plan’ for northern Uganda. It is not only a response to immediate post-conflict-specific issues, but is also meant to eliminate the great discrepancies in the development of the northern and the southern part of the country.

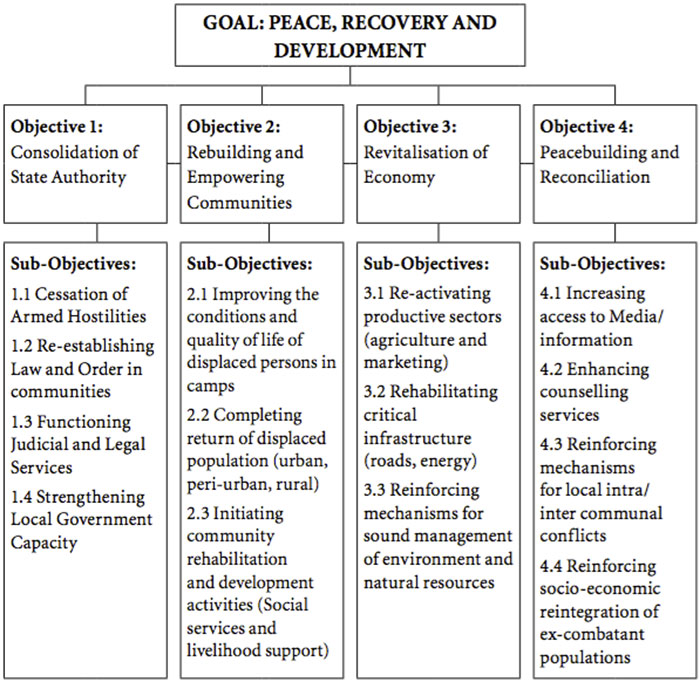

Through the adoption of a set of coherent programmes, the Government of Uganda seeks to achieve four Strategic Objectives in harmonisation with all stakeholders of the PRDP’s implementation process. These objectives include (1) Consolidation of State Authority; (2) Rebuilding and Empowering Communities; (3) Revitalisation of the Economy and; (4) Peace Building and Reconciliation. Please see figure 2.

Figure 2: PRDP Goals and Strategic Objectives

3.2 Coordination and implementation

Ongoing programmes in the North, such as the Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF), Northern Uganda Rehabilitation Programme (NUREP), Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Plan (KIDDP), Transition to Recovery Programme, Mine Action Programme, Northern Uganda Youth Rehabilitation Programme, Northern Uganda Youth Centre, North West Small Holder Agricultural Programme and the Northern Uganda Data Centre (NUDC) have all been realigned to the objectives of the PRDP.

The Department for Pacification and Development in the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) is in charge of the management and coordination of the PRDP, which is spearheaded by the Undersecretary for Pacification and Development. The government’s efforts to realise the various Strategic Objectives are testimony to its great commitment to stabilise and recover northern Uganda. All development actors, governmental and non-governmental, are expected to align their interventions in northern Uganda according to the PRDP framework.

In the framework of the PRDP, sector technical planning and coordination will continue to be done by the Sector Ministries and Local Governments (GoU 2007). Hence, execution is to a large part performed under the regular system and procedures for the implementation of sector programmes and district development plans (DDP). The Chief Administrative Officers (CAOs) are responsible for the general management and coordination of the PRDP at the Local Government Level, i.e. developing implementation plans and overseeing and managing the PRDP. In each PRDP district the CAO appoints a PRDP Liaison Officer whose task is to follow up the implementation of the PRDP in close collaboration with all the stakeholders that are operating in a given district.

The PRDP has a Technical Working Group (PRDP TWG) which is primarily in charge of the harmonisation of all actors involved in the recovery process in northern Uganda under the framework of the PRDP, as well as of the coordination of the PRDP itself. This entails the effective steering of PRDP Special Programmes and projects such as KIDDP, NUDC, and NUSAF2. Besides ensuring that activities do not overlap and that PRDP’s framework design and government policies are adhered to in implementation, the TWG is to foster synergies amongst all stakeholders engaged in recovery interventions. Moreover, it is the body coordinating the submissions of sector and agency budgets and Harmonised Sector Work Plans for consideration under resource mapping. The TWG also receives and analyses progress reports, informs decision making, identifies challenges and obstacles to a successful recovery and advises on their implementation.

Full-scale implementation started in July 2009 and it is currently programmed to run until June 2012. Forty District Local Governments and seven Municipal Local Governments implemented activities in the four sectors of education, health, roads and water. The Uganda Police Force and Uganda Prisons Services implemented activities related to the Enhancement of State Authority under strategic objective 1. The other agency involved in the implementation of PRDP activities is the Amnesty Commission. The priorities in the district PRDP work plans were decided by the districts in consultation with the area members of parliament. All the implementing districts prepared annual work plans containing their priorities duly approved by their district councils and submitted to the office of the prime minister for final approval. The Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED) and the Northern Uganda Data Centre (NUDC) provided a format to enable the districts to report progress on the implementation of PRDP activities.

3.3 Achievements

The resettlement programme to support the return of the IDPs commissioned by the OPM has made remarkable achievements. To support food production, the OPM introduced a tractor hire scheme which has resulted in cultivation of over 7 900 acres of agricultural land for crop plantation. The government also provided 350 ox ploughs, 700 oxen and 500 heifers to support local farmers in agricultural production in Lango sub-region (GoU 2011). Under the Karamoja Food Security Action Plan (KFSAP), the government has supported communities in the sub-region to participate in food growing and a number of water points have been constructed to support agricultural production. For example, GoU hired a private tractor company to plough 2 200 acres of land in Karamoja for vulnerable people and provided seeds, cassava cuttings, potatoes and vines to boost food production.

Furthermore, as part of the settlement incentive, the GoU has procured and distributed 32 000 corrugated iron sheets to the returning IDPs to facilitate the construction of houses. A low-cost housing scheme using hydraform was piloted by the government in the Karamoja, Teso and Acholi sub-regions. In Karamoja sub-region 40 low-cost housing units and a health centre were constructed at Nadunget and Campswahili. The GoU has also trained 80 youth in brick making and the construction of low-cost housing units (GoU 2011).

In order to address strategic objective 2 of the PRDP, the GoU initiated NUSAF2. A systematic roadmap to roll out the project in the war-ravaged regions was developed by the OPM. NUSAF2 was designed on the basis of a community demand specifically focused on livelihood improvement and access to socio-economic services. As part of the intervention, a number of public infrastructure investments has been made as summarised in table 1 below:

Table 1: Public infrastructure development

| Infrastructure | Number |

| Primary school classrooms | 525 |

| Teachers’ houses | 239 |

| Construction roads | 1 200 km |

| Houses for Acholi Chiefs | 49 |

| Boreholes | 390 |

| Shallow wells | 33 |

Source: GoU 2011

Shortcomings and challenges in the planning and the implementation of the PRDP

4.1 Inherent weaknesses within the PRDP

The PRDP at first glance may be seen as a conflict-sensitive development programme with an attractive title: ‘Peace, Recovery and Development Plan for Northern Uganda’. At its very inception, however, the PRDP was faced with challenging problems, such as finding conceptual clarity, an appropriate model, sufficient institutional capacity and adequate funding.

The critics of the PRDP challenged the government to provide a comprehensive conflict-sensitive development policy framework for the war-ravaged northern Uganda. But, according to Clausen and others (2008:35), ‘the PRDP emerges from a historical background of GoU policies and programmes towards the North that have been highly conflict insensitive. Against this background the PRDP rests on an insufficient [sic] detailed and differentiated conflict analysis, mainly focusing on symptoms rather than the underlying dynamics of the conflict’.

Women’s contributions to war and peace in northern Uganda have been underestimated by the PRDP. A number of studies conducted in the region (International Alert 2010; Isis-WICCE 2000) established that conflict worsens existing patterns of gender-based violence, especially sexual violence, as communities’ values are disregarded during and after conflicts. Women in northern Uganda were subjected to different forms of gender-based violence including abduction, sexual slavery, gang rape, forced marriage and maiming of body parts. Violence against women also extends to denial of the right to economic resources like land due to the breakdown in the traditional system of land management.

The PRDP investment was mainly focused on infrastructural development – neglecting the crucial peacebuilding and reconciliation strategic objective. Both of these key aspects were included in the plan, but they were ‘mainly boxed into the fourth strategic objective of peace building, recovery and reconciliation and not sufficiently recognised under the other objectives’ (Clausen et al. 2008:35).

4.2 Institutional capacity challenges

The capacity to include PRDP priorities in regular plans and programmes and execute them as planned is adequate at national level. However, in PRDP districts there are significant human resource and capacity constraints. Whereas local governments all over the country experience staffing constraints, the situation in the north has been exacerbated by over two decades of conflict. Government structures in most parts of the region were destroyed and replaced by camp commandants. With the influx of humanitarian assistance, the North has become a relief-dominated economy while the district authorities have very few resources at their disposal. Staff attrition is extremely high and the average staffing capacity in the region ranges between 35% and 55% of the approved positions (GoU 2006). Many critical positions in both the administrative and technical cadres remain unfilled. The situation is even worse at the lower local governments where many positions of Sub-county and Parish chiefs are frequently occupied by persons in acting capacity. Among the technical departments, the health sector is the worst affected due to an acute shortage of health workers in the region. An assessment conducted by the Ministry of Local Government (MoLG) in December 2006 indicated that the Acholi region had a 63,2% gap of unfilled staffing, West Nile 56,1%, Lango 51,1%, Teso 44,6% and Karamoja 50%.

In addition to low staff numbers, many local governments in the conflict-affected districts also lack basic office facilities, equipment and logistics to support their operations. Because of the security threats, poor living conditions, lack of social infrastructure, lack of basic office amenities and low local revenue the districts continue to experience difficulties in attracting and retaining qualified staff. This has an adverse impact on key functions as internal audit and control. Staffing gaps in some districts have also been attributed to the creation of new districts which have further depleted the older districts of their staff complement. Low management capacity, weak discipline in relation to GoU regulations and weak internal control systems have resulted in significant amounts of unauthorised expenditures in many districts. The rectifying factor would be to closely monitor compliance with GoU public financial management regulations and ensure that audit qualifications are followed up.

4.3 Limited financial resources

As a master plan, the PRDP is estimated to cost 606 million US dollars over a three year period. Sector-specific costing exercises, however, indicate a much higher level of financial requirement to reduce the regional imbalance between North and South in the various sectors (Clausen et al. 2008). Furthermore, there are disagreements between the different government institutions as to whether the costing of PRDP was an estimate of the need for additional funding or whether it included current allocations (Clausen et al. 2008:44). Funding for the PRDP priorities are partially based on the assumption that humanitarian assistance channelled by donors through NGOs and UN agencies for northern Uganda can be shifted to regular on-budget support for PRDP (Bailey et al. 2009). Although some donors have indicated increased transitional and development funding to the North, there is a gap in funding for the transition from humanitarian assistance to longer-term development funding. For most donors, humanitarian assistance is allocated through global votes and prioritised between emergency situations and not allocated to a specific country (Bailey et al. 2009).

In the fiscal year 2009/2010, which was the first full-scale year of PRDP implementation, the contribution of the Government of Uganda amounted to UGX 100 billion, details of which are provided in table 2 below. While UGX 76 369 billion was disbursed directly to the 40 District Local Governments in accordance with their Harmonised Sector Work Plans, UGX 3 601 billion was allocated to the 7 Municipal Local Governments. On the basis of the sector work plans harmonised with the Office of the Prime Minister, the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development released a total of UGX 79 466 billion representing 99,4% of the total allocations in the fiscal year 2009/2010.

Table 2: PRDP Allocation for FY2009/2010

| Sectors/Agencies | Amount (UGX) |

| Uganda Police Force | 6 256 783 390 |

| Institutional support for coordination and monitoring | 2 781 343 405 |

| Uganda Prisons Services | 1 602 609 735 |

| Amnesty Commission | 1 200 000 000 |

| Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs | 3 189 110 470 |

| Karamoja Development Programme | 5 000 000 000 |

| District local governments | 76 369 153 000 |

| Municipal local governments | 3 601 153 000 |

| Grand Total | 100 000 000 000 |

Source: GoU 2010

The PRDP budget also includes on-budget and off-budget support as well as funds provided for Special Programmes. On-budget support to the PRDP is project funding to the government by donors who support specific PRDP-related activities implemented by central government over a fixed period of time. Activities funded by this basket fund are managed by different institutions and primarily use government budgeting, procurement, accounting and reporting systems. Off-budget support refers to donor expenditures channelled through NGOs or implementing organisations. However, this includes only those projects which are in line with the PRDP’s strategic objectives, in particular with strategic objectives 2 and 4, and are implemented directly by UN or NGOs (GoU 2010).

In 2008, a Joint Financing Agreement (JFA) was established to contribute towards the on-budget funding of the PRDP. Norway and Sweden contributed in the fiscal year 2009/2010 NOK 30 million (approximately USD 4,4 million) and SEK 15 million (approximately USD 1,9 million) to the budget fund, which supported the PRDP districts in the priority sectors of health, roads, education and water. In the coming fiscal year 2010/2011, the two countries will continue to contribute to the JFA, joined by Denmark and Ireland totalling approximately USD 12 million.

4.4 Implementation challenges

The implementation of the PRDP and its possible impacts have been intensely discussed and highly criticised by academics, policy analysts and the civil society (Salborn 2010). An accurate evaluation of the achievements made by the implementation plan is still missing. As a guiding principle, the PRDP implementing districts were required to come up with their annual priority interventions through a consultative process involving all stakeholders, notably the members of parliament and political leadership in the districts. The lower local units were also expected to set their priorities and submit them to the districts for consideration. These PRDP priority activities are presented by the District Technical Planning Committee (DTPC) to the District Council (DC) for final approval. However, this process has several challenges ranging from lack of information, poor communication to inadequate capacities of planning teams.

The Office of the Prime Minister received a number of complaints from the PRDP implementing districts (GoU 2010). Most district councillors never gave any feedback to the sub-counties they represent on the prioritisation decisions of the councils and the spirit under which they were taken. The apparent poor working relations between the members of parliament and some district leaders resulted in poor flow of information. Some districts also approved the PRDP work plans without subjecting them to serious scrutiny by the stakeholders, which resulted in duplication.

There was duplication of work plans between line ministries and local governments in a number of districts. For example, Budaka district and the Ministry of Water and Environment both planned to construct motorised boreholes at Iki-Iki Town Board in the same FY 2009/10. Similarly in Moyo district, the construction of a staff house at Abeso H/C II in Metu sub-county worth UGX 67 980 000 was planned for twice – under the normal Primary Health Care (PHC) development grant to the district and also under PRDP.

Furthermore, unclear policy guidelines have resulted in conflicting prioritisation, lengthy procurement processes and high costs of investment. Coupled with poor public information and limited understanding of the PRDP, there are unrealistic expectations held by implementing districts. For example, members of Lira district local council planned to build a 40 000 seat modern stadium named after John Akiibua, a former olympic gold medallist, and an airport at Anai using PRDP funds (Omara 2009).

There are cases where the implementation of the PRDP has created conflicts, which it then had to mitigate. For instance, the rehabilitation of Anamido-Adero landing site road in Amolator district led to destroyed property and crops, which caused protest from the community. Without consulting the community, the contractor abandoned the procurement requirements and opened up a new road instead of rehabilitating the existing road. The intended outcome of strengthening local government capacity and empowering local communities was at stake. Land use and crop destruction are now the new sources of conflict in the district.

Another concern was the Government’s creation of new districts, which posed a challenge in human resource deficits coupled with poor service delivery. Many times, the leaders from the already planned for districts have raised concerns about the reduction in funding because new districts have to be catered for. For example, a serious capacity gap forced Nakapiripirit district to use the Kapchorwa district contracts committee. The lengthy procurement process slowed down the implementation of the PRDP programmes. Other districts in similar procurement difficulties were Busia and Budaka. Also a number of districts such as Pader and Kumi have failed to adhere to their work plans and lack the capacity to implement them.

In some cases there is a tension between some district local governments and the sector ministries about their mandate in the implementation of the PRDP activities. For example, the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) has moved beyond its mandate of ensuring quality through provision of technical support to ensure compliance with line sector norms and standards in the implementation of PRDP activities. In Manafwa district in particular the District Education Officer (DEO) with instruction from the MoES took over the role of managing the funds under the education investments, disregarding the decision of the district council. Such kinds of disagreements were also reported in Sironko, Oyam and Buliisa districts.

A similar challenge was also presented by the Ministry of Works, Transport and Communication (MoWTC) and Butaleja district. The MoWTC had unique standards for the determination of interventions under PRDP in the road sector. Whereas trunk/national roads remained the responsibility of MoWTC, districts continued to manage and plan for community/access roads and district/feeder roads under PRDP. However, the case of Butaleja district and MoWTC planning to rehabilitate the same Nampologoma-Mawaga-Kaiti-Hasahya road in Kachonga-Naweyo sub-counties raised a question about the clarity of mandates.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The PRDP as a post-conflict recovery strategy for building sustainable peace, eradicating poverty and improving the welfare of the people of northern Uganda is a good programme. It is the overall plan for accelerating development in northern Uganda above the regular national budget within the National Development Plan (NDP). In the past two years of the implementation of the plan, a remarkable amount of social service infrastructure has been built to support the return of the IDPs. The objective of this component is to improve access to basic socio-economic services through rehabilitation and improvement of existing community infrastructure such as schools, water points, skills training centres, health centres, teachers’ houses and sanitation facilities.

Despite the remarkable progress, northern Uganda still lags behind the rest of the country in health, education and general infrastructure. Conceptual and capacity problems continue to pose a serious threat to the government’s commitment to support the recovery of northern Uganda. The major PRDP investment was devoted to the rebuilding of the physical components of the region while only a negligible investment was made towards rebuilding people’s lives. The objective 4 of the PRDP, which provides for peacebuilding and reconciliation has fallen short of the envisioned output. The plan is ill-equipped to comprehensively address the over two decades of deep-seated human anguish, devastation and psychosocial trauma caused by the civil war. PRDP lacks the mechanism to institute social justice through non-discriminatory and equitable accountability of the state and non-state parties to women, men and children in northern Uganda.

The envisioned outcome of the PRDP is to ensure continuous prevalence of peace in northern Uganda. The peacebuilding and reconciliation process requires increasing access to information, enhancing counselling services, establishing mechanisms for communal and national conflict resolution and reinforcing the integration of IDPs and ex-combatants in their communities. There should be a deliberate effort to strengthen the capacity of local governments and informal leadership structures to deliver services to returning populations.

At the moment, monitoring the implementation of the PRDP is being done at various levels. The OPM has generated results matrices for monitoring the implementation of the various programmes within the plan. The donors and donor working groups have also developed matrices for monitoring peace and development impacts. Local civil society and other international civil society groups have also put in place mechanisms to monitor the implementation of projects at district, sub-county and village level. All these initiatives are important to ensure that services are provided as planned and that they fit within the objectives of the PRDP.

Furthermore, resource allocations should be conflict-sensitive and ensure that the sector plans to improve the delivery services relate to addressing the deep-seated conflict situations in the regions. Attention should also be given to building the capacity of the local governments to enable them to deliver accountable and unbiased service of the best possible quality. This calls for comprehensible guidelines and monitoring mechanisms that can eliminate duplication and corruption. Perhaps in some cases there is need for an appropriate sequencing of result-oriented interventions. Free flow of information and community participation will create a sense of legitimacy, ownership and sustainability of the PRDP.

Finally, it is well known that rebuilding war-ravaged areas need a lot of resources. It is an area to which the government must give priority in order to improve development outcomes in the impoverished region. Preventing and ending conflicts, and ensuring that they do not recur should be the core agenda of the PRDP. Therefore, contextual analysis of the overall recovery process, evidence-based advocacy and technical support to improve the recovery and peacebuilding impact should support the implementation process. These responsibilities cannot be met by relying on humanitarian agencies and development partners to provide core functions such as health, education, water and agricultural support. The government should be at the frontline and must demonstrate the will to comprehensively address the recovery of northern Uganda.

Sources

- Allen, Tim 2006. Tiial justice: The International Criminal Court and the Lord’s Resistance Army. London, Zed Books.

- Bailey, Sarah, Sara Pavanello, Samir Elhawary and Soreha O’Callaghan 2009. Early recovery: An overview of policy debates and operational challenges. Humanitarian Policy Group Working Paper. London, Overseas Development Institute.

- Claussen, Jens, Randi Lotsberg, Anne Nkutu and Erlend Nordby 2008. Appraisal of the Peace, Recovery and Development Plan for Northern Uganda. Oslo, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

- Das, Rekha and Anne Nkutu 2008. Evaluation of general food distribution in Northern Uganda: Gulu, Amuru and Kitgum Districts 2005–2008. Kampala, Norwegian Refugee Council.

- Doom, Ruddy and Koen Vlassenroot 1999. Kony’s message: A new Koine? The Lord’s Resistance Army in Northern Uganda. African Affairs, 98, pp. 5–36.

- Gersony, Robert 1997. The anguish of Northern Uganda: Results of a field-based assessment of the civil conflict in Northern Uganda. Kampala, USAID.

- Government of Uganda (GoU) 2006. A rapid assessment study for support to local governments in Northern Uganda. Kampala, Ministry of Local Government.

- Government of Uganda 2007. Peace, Recovery and Development Plan for Northern Uganda 2007–2010. Kampala, Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED).

- Government of Uganda 2010. Reconstructing Northern Uganda takes shape: Achievements of the full-scale implementation of PRDP during FY 2009/2010 accountability. Kampala, Office of the Prime Minister.

- Government of Uganda 2011. Peace, Recovery and Development: How far and which way? Kampala, Office of the Prime Minister.

- Hickey, Samuel 2003. The politics of staying poor in Uganda. CPRC Working Paper 37. Manchester, Chronic Poverty Research Centre.

- International Alert 2010. Changing fortunes: Women’s economic opportunities in post-war Northern Uganda. Investing in Peace, Issue No. 3.

- Isis-WICCE 2000. Documenting women’s experiences of armed conflict situations in Uganda: The case of Gulu district, 1986–1999. Kampala, Isis Women’s International Cross Cultural Exchange.

- Kasozi, Abdu B.K. 1994. The social origins of violence in Uganda 1964–1985. Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Latigo, James Ojara 2008. Northern Uganda: Tradition-based practices in the Acholi region. In: Huyse, Luc and Mark Salter eds. Traditional justice and reconciliation after violent conflict: Learning from African experiences. Stockholm, International IDEA.

- Mamdani, Mahmood 1999. Politics and class formation in Uganda. Kampala, Fountain Publishers.

- Martin, Ellen 2010. Capacity-building and partnership in Northern Uganda. Humanitarian Practice Network, Issue 46, March 2010.

- Omara, James 2009. Lira plans to build airport and modern stadium using PRDP funds. Available from: <http://www.adungu.org/?cat=33> [Accessed 5 December 2010].

- Pham, Phuong, Patrick Vinck, Marieke Wierda, Eric Stover and Adrian di Giovanni 2005. Forgotten voices: A population-based survey of attitudes about peace and justice in Northern Uganda. Berkeley, The International Centre for Transitional Justice and the Human Rights Centre.

- Salborn, Etienne 2010. Requirements for successful return and resettlement after long-term internal displacement. Nordestedt, GRIN Verlag.

- Tripp, Aili Mari 2010. Museveni’s Uganda: Paradoxes of power in a hybrid regime. Boulder/London, Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) 2003. Uganda National Household Survey 2002/2003 Report on the Socio-economic Module. Kampala, UBOS.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2006. Uganda National Household Survey 2005/2006 Report on the Socio-economic Module. Kampala, UBOS.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2007. Uganda Human Development Report 2007: Rediscovering Agriculture for Human Development. Kampala, UNDP.

- United Nations Development Programme 2008. Committed to Northern Uganda’s recovery. Special Edition: Crisis Prevention and Recovery programme. Kampala,The United Nations Development Programme in Uganda Communications Group Newsletter.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2010. 6th December 2010, Camp phase-out update for Acholi, Lango, Teso and Madi Sub-regions. Kampala, UNHCR.

Notes

- By the time of finalising this paper, the number of the IDP camps has reduced to nine and the number of the transit sites reduced from 285 to 210. According to the UNHCR Factsheet of 31 March 2011, by the end of March 2011 there were 73 239 IDPs in Northern Uganda. This comprises 26 390 IDPs remaining in active camps and 46 849 in the decommissioned camps.